Katsushika Hokusai, Japan’s best known artist, is ironically Japan’s least Japanese artist. Japan’s best known woodblock print, The Great Wave, is very un-Japanese. Welcome to the artist often known as Hokusai.

Hokusai (1760-1849) lived during the Tokugawa period (1600 to 1867). In a Japan of traditional Confucian values and feudal regimentation, Hokusai was a thoroughly Bohemian artist: cocky, quarrelsome, restless, aggressive, and sensational. He fought with his teachers and was often thrown out of art schools. As a stubborn artistic genius, he was single-mindedly obsessed with art. Hokusai left over 30,000 works, including silk paintings, woodblock prints, picture books, manga, travel illustrations, erotic illustrations, paintings, and sketches. Some of his paintings were public spectacles which measured over 200 sq. meters (2,000 sq. feet.) He didn’t care much for being sensible or social respect; he signed one of his last works as “The Art-Crazy Old Man”. In his 89 years, Hokusai changed his name some thirty times (Hokusai wasn’t his real name) and lived in at least ninety homes. We laugh and recognize him as an artist, but wait, that’s because we see him as a Western artist, long before the West arrived in Japan.

“From the age of six I had a mania for drawing the shapes of things. When I was fifty I had published a universe of designs. but all I have done before the the age of seventy is not worth bothering with. At seventy five I’ll have learned something of the pattern of nature, of animals, of plants, of trees, birds, fish and insects. When I am eighty you will see real progress. At ninety I shall have cut my way deeply into the mystery of life itself. At a hundred I shall be a marvelous artist. At a hundred and ten everything I create; a dot, a line, will jump to life as never before. To all of you who are going to live as long as I do, I promise to keep my word. I am writing this in my old age. I used to call myself Hokosai, but today I sign my self ‘The Old Man Mad About Drawing.” — Hokusai

Hokusai started out as a art student of woodblocks and paintings. During the 600-year Shogun period, Japan had sealed itself off from the rest of the world. Contact with Western culture was forbidden. Nevertheless, Hokusai discovered and studied the European copper-plate engravings that were being smuggled into the country. Here he learned about shading, coloring, realism, and landscape perspective. He introduced all of these elements into woodblock and ukiyo-e art and thus revolutionized and invigorated Japanese art.

Although Chinese and Japanese paintings had been using long distance landscape views for 1,500 years, this style had never entered the woodblock print. Ukiyo-e woodblocks were produced for bourgeoisie city gentry who wanted images of street life, sumo wrestlers, and geishas. The countryside and peasants were ignored.

What was the influence on Hokusai?

In Holland in the late 1500s, artists such as Claes Jansz Visscher and Willem Buytewech developed landscape art, which focused on topographically-correct landscape representation. Landscape art reached its peak between 1630 and 1660 through Rembrandt van Rijn, Jacob van Ruisdael, and Jan van Goyen. By the late 1700s, these Dutch paintings had become so common that the etchings were used as cheap illustrations. Dutch merchants smuggled their goods into Japan. These wares were often wrapped in paper that had been illustrated with these etchings. For Hokusai and other artists, the thrown-away wrappers were more interesting than the imports.

Hokusai learned from Dutch and French pastoral landscapes with their perspective, shading, and realistic shadows and turned them into Japanese landscapes. More importantly, he introduced the serenity of nature and the unity of man and his surroundings into Japanese popular art. Instead of shoguns, samurai, and their geishas, which were the common topics of Japanese illustrative art at the time, Hokusai placed the common man into his woodblocks, moving the emphasis away from the aristocrats and to the rest of humanity. In The Great Wave, tiny humans are tossed around under giant waves, while enormous Mt. Fuji is a hill in the distance.

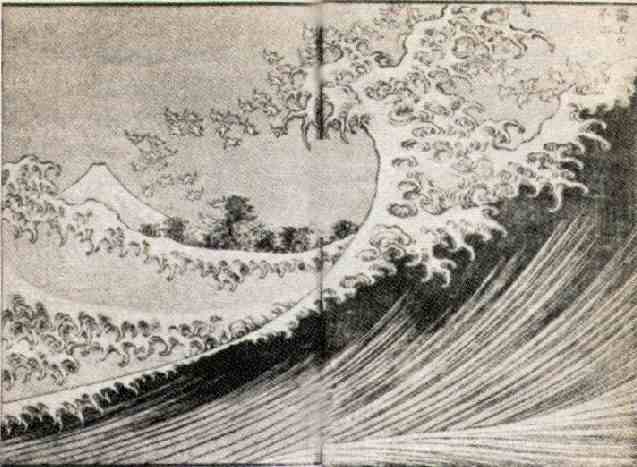

The Breaking Wave Off Kanagawa. Also called The Great Wave. Woodblock print from Hokusai’s series Thirty-six Views of Fuji, which are the high point of Japanese prints. The original is at the Hakone Museum in Japan.

Hokusai’s most famous picture and easily Japan’s most famous image is a seascape with Mt. Fuji. The waves form a frame through which we see Mt. Fuji in the distance. Hokusai loved to depict water in motion: the foam of the wave is breaking into claws which grasp for the fishermen. The large wave forms a massive yin to the yang of empty space under it. The impending crash of the wave brings tension into the painting. In the foreground, a small peaked wave forms a miniature Mt. Fuji, which is repeated hundreds of miles away in the enormous Mt. Fuji which shrinks through perspective; the wavelet is larger than the mountain. Instead of shoguns and nobility, we see tiny fishermen huddled into their sleek crafts as they slide down a wave and dive straight into the next wave to get to the other side. The yin violence of Nature is counterbalanced by the yang relaxed confidence of expert fishermen. Although it’s a sea storm, the sun is shining.

To Westerners, this woodblock seems to be the quintessential Japanese image, yet it’s quite un-Japanese. Traditional Japanese would have never painted lower-class fishermen (at the time, fishermen were one of the lowest and most despised of Japanese social classes); Japanese ignored nature; they would not have used perspective; they wouldn’t have paid much attention to the subtle shading of the sky. We like the woodblock print because it’s familiar to us. The elements of this Japanese pastoral painting originated in Western art: it includes landscape, long-distance perspective, nature, and ordinary humans, all of which were foreign to Japanese art at the time. The Giant Wave is actually a Western painting, seen through Japanese eyes.

Hokusai didn’t merely use Western art. He transformed Dutch pastoral paintings by adding the Japanese style of flattening and the use of color surfaces as a element. By the the 1880’s, Japanese prints were the rage in Western culture and Hokusai’s prints were studied by young European artists, such as Van Gogh and Whistler, in a style called Japonaiserie. Thus Western painting returned to the West.

The Great Wave is from Hokusai’s later years. He did a similar work many years before:

Fuji Seen From the Sea. 1834. Woodblock. From the series A Hundred Views of Mt. Fuji.

In this wave, the foam breaks up into a flock of birds. This wave is quite humorous; it disperses itself into wind. Without the boats and the width of the other print, this work is not as dramatic. The tension of the sea is drawn out through lines up the side of the wave.

Peonies and Canary. Woodblock. National Museum at Tokyo. Click for larger image.

Before Hokusai, ukiyo-e artists such as Utamaro and Kunsai drew birds and flowers as illustrations in books. Hokusai was the first artist to make these bird-and-flower artworks primarily as prints.

Flock of Chickens. Woodblock. 1830-1844. National Museum at Tokyo.

With a swirl of plumes, the flock of roosters form a circle of motion, similar to many of Hokusai’s water paintings. The birds are precise and realistic. The woodblock could be a technical illustration to a ornithologist’s text on breeds of roosters. Hokusai was inspired by European scientific illustrations and the European respect for the beauty of Nature. The rooster at the right-middle has a very happy, contented expression. This is an example of Hokusai’s bird-and-flowers illustrations.

The Hanging Lantern of Kaya Temple. Woodblock. Collection of Shozaburo Watanabe.

This is an early example of Hokusai’s landscapes. First of all, it’s set at a real location, the Sumida River. The trees are done with chiarscuro shading in the European style. But it’s not entirely realistic: the water’s waves are still in the Chinese stylized fashion. The perspective is also wrong: the tail of the boat is higher than the houses behind it, and the boat appears to be above the house at the front of the illustration. Hokusai is still experimenting and learning various elements, and hasn’t yet begun to unify them. Note the playful extension of the birdhouse out of the picture at the upper left.

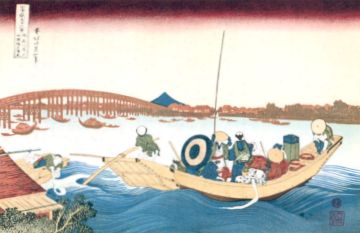

Sunset over Ryogoku Bridge. From 36 Views of Mt. Fuji. Woodblock. Hakone Museum.

By the time Hokusai began his Mt. Fuji series, he was able to unify vast persepectives into calm paintings. Here, a boatload of passangers gaze at Mt. Fuji, in a quiet, plebian scene of ordinary people in their daily life. This realism is Hokusai’s unique contribution to Japanese art. This print is from the 1840s, when Hokusai was already in his 70s and fully developed in his artistic skill.

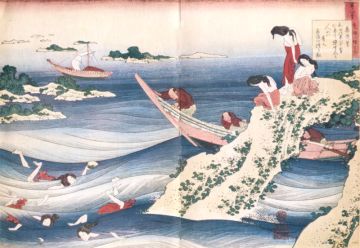

Sangi Takamura. Women diving for abalone. From Hundred Poems Explained by a Nurse. Woodblock. National Museum, Tokyo.

This is from the late 1840s. A group of women dive for abalone. Click the image and study the women at the lower left in the large version. They are interlaced through waves and water.

Courtesan. Painting on silk. 1812-1821. Collection of Moshichi Yoshiara.

The courtesan is almost buried the weight of her luxuriously textured and detailed kimono. Hokusai pays attention to precision and detail of the cloth. The important issue is the flattening of surfaces and the use of color fields. This became a major influence on Western artists in the late 1800s into the 1900s.

Fighting Cocks. Painting on silk. Hakone Museum.

Hokusai also did freehand paintings on paper and silk. Very few Japanese artists were able to work in both woodblock and painting. Note the rooster’s very proud and agressive stance.

Hokusai Manga. Sketch on paper.

Hokusai also drew thousands of small sketches. These are called Manga in Japanese. There are more than 15 volumes of Hokusai manga. The fisherman and his load of tuna are delicately drawn in three-dimensional perspective.