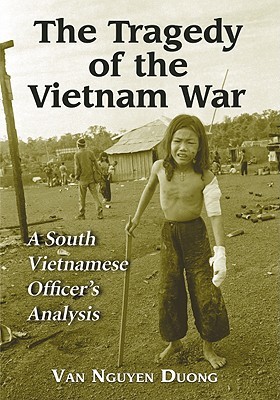

In the acknowledgements of my book The Tragedy of the Vietnam War, I wrote,

In the acknowledgements of my book The Tragedy of the Vietnam War, I wrote,

“We maintain our pride for having once served in our Armed Forces to pursue aspirations of independence, justice, and freedom for our people. An army may be disbanded but its spirit is eternal. Such is the case of the Republic of Vietnam Armed Forces.(1)

Unfortunately we could not realize our dream and aspiration. On that bitter day of April 30th, 1975, we were forced to give up our arms. We agonizingly suffered the disbanding of our armed forces and the collapse of our democracy. The war was lost.

More than 34 years after the end of the war, even overloaded with misfortune, many of us have still survive tediously haunted by the traumas of the past. I myself have experienced nightmares from the irritant war loss for thirteen years in different communist “reeducation camps.” I have learned from these painful days that we could not change the past but had to get through it for a better change in the future. We have to learn our lessons from the past in order to build the future. It is also a better way for us to get away from traumas and to heal our wounded minds. I became determined to penetrate to the heart of these war matters for the purpose of clarifying my mind.

I was released from these communist concentration camps in April 1988 and came to America in 1991. This blessed opportunity allowed me to realize my longing. Since September 1994, I have put myself into studying English, researching documents, and finding facts. I began to draft my first manuscript on the war in Vietnam. Fortunately after 15 years of hard work, determination, resilience and patience, I have achieved my goal. My work was published by McFarland & Company in September 2008.

THE HAUNT OF THE PAST: THE ATROCIOUS SOCIALIST REVOLUTION IN SOUTH VIETNAM

THE HAUNT OF THE PAST: THE ATROCIOUS SOCIALIST REVOLUTION IN SOUTH VIETNAM

Immediately after seizing power in South Vietnam on April 30, 1975, the Vietnamese communist leaders sent more than 250,000 South Vietnamese officers, policemen and officials to their “reeducation camps” around the country for years. Thousands died of exhaustion from hard labor, hunger and illnesses. Others were killed by torture and execution in these camps unknown to the world. The communists chased out 300,000 of our disabled veterans and wounded soldiers from every military sanatorium or hospital transforming them into homeless people who have –since then– dragged their miserable lives in all corners of South Vietnam. Almost a million RVNAF officers’ wives and children were forced to relocate to remote “new economic zones” to endure hard labor for living. Moreover, a few months later, they ordered people to dig up the graves of our heroes at cemeteries in Saigon, Biên Hòa and throughout the South and to discard the remains so that plots could be used for the burial of communist soldiers. We suffered our pain in silence. It was tragic.

However, the outcome of the war would lead to a greater tragedy for the South Vietnamese – some 26 million of them. With the so-called “Social Socialist Revolution” -Cách Mạng xã hội Xã Hội Chủ Nghĩa- Vietnamese communist leaders tried to uproot all vestiges of the formerly free society of South Vietnam in all domains, both physically and spiritually. In other words, they took fierce measures to transform the southern society by taking revenge on anyone associated in any form with the free regime of the South. Their victims were not only South Vietnamese officers and officials, but also leaders of all religions: Buddhist, Catholic, Christian, Cao Đài, Hòa Hảo; leaders of nationalist parties; intellectuals in the world of letters: writers, poets, novelists, professors, theoreticians, philosophers, and people from the press circles, owners, publishers, editors, journalists, columnists, and reporters. Most of them from 90,000 to 100,000 were arrested and put in jails or reeducation camps for various duration.

In the economic, agricultural, and industrial sectors, Vietnamese communist leaders confiscated all private lands, industrial factories, means of production, commercial establishments and stores–large or small–and properties of landowners, merchants and rich people around South Vietnam then transformed them into state properties and state factories. The communist policy of eradicating the comprador bourgeoisie –tư sản và mại bản– was vigorously executed swelling their concentration camps of more than 100,000 additional people. Social activities seriously stagnated after millions of people lost their properties and tens of millions of others lost their incomes, because of unemployment and prohibition of practicing free commerce, business, and wholesale or retail trade. In rural areas, collective farms and in urban sectors state enterprises were incapable of producing food and furnishing commodities for the people. Stagnation of the national economy was inevitable and the poverty of the Vietnamese people was visible, all of which would hinder the nation for decades.

The red deluge of April 1975 in South Vietnam has not only destroyed the young and free southern regime, but also uprooted its society, which was founded on national traditions, Confucianism, Buddhism, Taoism, and religious beliefs for thousands of years. Public fear emerged from every corner of the land: fear of doing, fear of talking, fear of being accused of being anti-regime, and so on. Whether a soldier or a peasant, a teacher or a student, a man or a woman, an elderly person or a young child, all of their lives were exposed to danger every minute of the day. And we, people of the South did have the guts to face a new regime, which was based on idiocy, atrocity and immorality.

The vindictive measures of the Vietnamese communist leaders in their “Socialist revolution” would result in, first, the exodus of nearly three million of South Vietnamese. One third of them lost their lives in Indochinese forests or at seas. The word “boat people” was heard around the world. It has multiple meanings although the most lofty one was the “deadly-vote” against the heartless despotism of the Vietnamese communist leaders and the atrocious totalitarianism of their regime. These waves of Vietnamese exodus would have been the largest and most tragic in mankind’s history.

Second, these vindictive measures of the Vietnamese communist leaders led to a deeper division between the Vietnamese for generations. Last but not least, was the sorrowful loss of human resources–intellectuals and elites were killed, imprisoned or maltreated in the South or dispersed overseas. A country would eventually fade away if it got rid of its intelligentsia. This is the case of Vietnam today. If national power remains in the hands of a class of corrupt, narrow-minded and blind-sided communist leaders, Vietnam would meet greater catastrophes in the future.

All of these disastrous consequences resulted from the loss of South Vietnam, the collapse of its regime, and the disbanding of its armed forces. We, South Vietnamese people, should accept our defeat and learn our lessons.

Vietnamese communist leaders’ atrocity, cruelty and inhumanity present at every stage of the war had seriously affected its outcome. Hồ Chí Minh and his comrades of the Vietnamese Workers’ Party (VWP) had waged “an armed struggle” to seize the power according to communist dogmas. Proletarian revolution thus was neither a war fought for a “people’s liberation,” nor for a “class liberation.” These beautiful terms were merely communist propaganda’s catchphrases.

Yes, brutal armed struggle to establish the totalitarian communist regime in Vietnam was the true nature and real cause of Hồ Chí Minh and Party’s leaders in their protracted war (chiến tranh trường kỳ).

LESSONS LEARNED FROM THE FIRST VIETNAM WAR

After two American atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki respectively on August 6 and 9, 1945, Japan collapsed and declared its intentions to surrender to Allied Forces on August 10. In Vietnam, the Japanese surrendered on August 15 and moved to a state of “inaction” waiting for the disarmament.

According to the Potsdam Agreements in July 1945, from August 18, 1945, the Chinese Nationalist Forces of Chang Kei-Shek would occupy North Vietnam and part of Central Vietnam north of the 16th parallel while British forces would control the southern half of the Indochinese peninsula.

-On August 17, the Vietnamese communists in North Vietnam staged a brief uprising and two days later seized control of Hanoi.

-On August 23, Prime Minister Trần Trọng Kim of the central government in Hue resigned and his cabinet disbanded.

-On August 24, Emperor Bảo Đại abdicated the throne under Hồ Chí Minh’s entreaty.(2)

-On August 26, Hồ returned to Hanoi accompanied by the armed propaganda unit of Võ Nguyên Giáp and the American OSS Deer Team (OSS: Office of Strategic Services, the forerunner of the CIA) of Major Archimedes Patti who had closed relations with Hồ, trained Giáp’s 200 military cadres, and armed them with modern weapons in Pắc Bó.

-On September 2, in a festive ceremony at Hanoi’s Ba Đình Square Hồ Chí Minh declared the independence for the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) and formed a cabinet with all members of his Indochinese Communist Party. His Việt Minh front –or Mặt trận Việt Minh– immediately organized their “administrative committees and guerilla units” in provinces, districts and villages throughout the country.

However, just days after his declaration of independence, Hồ began to show his dogmatic and inhumane character of a communist leader by ordering those newly formed regional committees and guerillas to kill, execute and murder those who had worked for the French and Japanese or previously had any relations with them and those suspected of being traitors –Việt gian. Most executions were barbarously performed. Victims were tied alive separately or together in bundles like logs and thrown into rivers to float along waters for a slow drowning –mò tôm (literally hunting for shrimp); buried alive–chôn sống; beheaded with their heads dangling from bamboo poles and bodies cut into ribbons; beaten to death with arms and legs broken and skulls cracked. This was the case of Ngô Đình Khôi –President Diệm’s brother– and scholar Phạm Quỳnh, Bảo Đại’s Prime Minister (Lại Bộ Thượng Thư). Both Khôi and Quỳnh were arrested by the Việt Minh in Huế and murdered at Hắc Thú forest in Quảng Trị on September 6. This was the first phase of the Vietnamese communists’ mass butchery.

In South Vietnam, with the support of the British Royal Forces, which came to disarm the Japanese in the southern part of Indochina on September 12, 1945, a French company of paratroopers accompanied the British Gurkha Division to Saigon. The British commander, Brigadier General Douglas Gracey ordered the freeing of all French prisoners held by the Japanese and rearmed them for the protection of their compatriots. Skirmishes occurred at several places in Saigon between these French elements and Viet Minh guerillas. The French Expeditionary Forces (FEF) of General Jacques Philippe Leclerc with the support of British Admiral (Sir) Louis Mountbatten, Supreme allied commander in Southeast Asia came back to South Vietnam on September 21 and moved to recapture Saigon. They faced fierce resistance from Trần Văn Giàu’s Viet Minh guerilla units. This experienced communist leader in South Vietnam immediately changed his South Vietnamese Administrative Committee –Ủy ban hành chánh Nam Bộ– into the Committee for Resistance and Administration –Ủy ban hành chánh kháng chiến.

On September 23, 1945, Giàu and his deputy Nguyễn Bình (later Major General) declared a “scorched earth policy” –sách lược tiêu thổ kháng chiến and led their guerilla forces to the maquis -bưng biền– for a long standing resistance against the French. That day was considered to be the starting point of the First Vietnam War and Giàu’s strategy became stereotypical war, which was adapted by provincial committees for resistance and administrations in South Vietnam. French forces would easily capture empty or burned down cities because of tản cư –evacuation of residents– and tiêu thổ –scorched earth. In the Mekong delta in their pacification march, the French had incorporated local Cambodians into partisan units and let them cắp duồn –behead or stab to death– every Vietnamese, even children and women, in any of their operations. At the time, the scariest terms that frightened southern villagers ever heard were “mò tôm” of the Viet Minh and “cắp duồn” of the French-Cambodian partisans. Vietnamese innocents were caught between the two forces and tried to hide from both. By the end of 1945, the FEF controlled the majority of provinces in South and central Vietnam, except the countryside where guerilla warfare continued and lasted for many more years. French newly assigned High Commissioner in Indochina, Admiral d’Argenlieu through agreements would control Cambodia and Laos but Commander-in-chief of the FEF, General Leclerc would not send his units to pacify North Vietnam because Chinese nationalist forces of General Lu Han still camped in Hanoi, Hải Phòng and several provinces in North Vietnam. Thus these two highest French authorities in Indochina had to face a second front in their war for recovering the old Indochinese colonies and transforming them into the “associated states” of the French Union–a new form of colonialism. This was the triangular diplomatic and political front between the French, Chinese Nationalists, and the Viet Minh government.

A significant event happened, however, disrupted Hồ’s hope to lean on U.S. support and changed the course of the First Vietnam War. On September 4, eight days before the arrival of the British forces, the OSS sent its 404 Team to Saigon to free more than 200 American prisoners of war held in Japanese camps. This intelligence team satisfactorily accomplished its mission. Three weeks later, its leader Major Dewey was mistakenly killed in an ambush by Giàu’s guerillas. In mid-December 1945, all American intelligence teams–Patti’s Deer Team OSS 202 in Hanoi and the OSS 404 Team in Saigon–were ordered to leave Vietnam. Hồ then faced a dilemma. In the South, he could not control the war between the French and Giàu’s troops. In the North, he had to endure the crude requests by General Lu Han’s greedy Chinese army. Diplomatic and political negotiations with the French and Chinese were his last resort after the Americans had quietly abandoned him.

The triangular political games between the three parties began in the first quarter of 1946 and had produced incredible consequences:

-On February 28, France signed an agreement with the Chinese Nationalist government whereby all Chinese forces would withdraw from North Vietnam and allow the French to return to Indochina in exchange for the “restoration of various concessions, including the renunciation of French extra-territorial claims in China” (and an unknown quantity of ingot gold as compensation for Lu Han’s withdrawal from North Vietnam).(3)

-On March 3, 1946, after serious deals with General Lu Han, Hồ agreed to form a coalition government with the participation of the Vietnam Revolutionary United Association (Việt Nam Cách Mệnh Đồng Minh Hội) and the Vietnamese Nationalist Party’s (Việt Nam Quốc Dân Đảng or VNQDD) leaders such as Nguyễn Hải Thần, Huỳnh Thúc Kháng, Nguyễn Tường Tam and Vũ Hồng Khanh. He also offered the nationalists 70 seats in the National Assembly.

-On March 6, Hồ and Vũ Hồng Khanh signed with Jean Sainteny, French official delegate a “preliminary agreement” (hiệp định sơ bộ) which recognized Vietnam as a free state and member of the French Indochinese Federation in exchange for allowing French forces to relieve Chinese troops in North Vietnam. The agreement stated that it “would enter into effect immediately upon exchange of signatures.”(4)

In signing the agreement, Hồ displayed his subtle aim to join hands with the French “to kill two birds with a stone”–sending Chinese troops back to China and annihilating nationalist armed forces in North Vietnam. The French attained their goals and could immediately move troops to the North. Only Vũ Hồng Khanh, the VNQDĐ’s leader, was lured into Hồ’s trap. Vũ had under his command a division of several thousand troops camped in various locations in North Vietnam. They soon became targets to be destroyed by French forces. The term “free state” would lead to more talks between the DRVN’s delegates and French authorities at the Dalat Conference (April-May 1946) and Fontainebleau’s (June-August 1946). Both conferences failed simply because France did not want to relinquish its colonial rules and interests in the three countries of Indochina but instead wanted to transform them into a new form of colonialism. Indeed on May 6, before leaving Dalat, French chief of delegation Max Andre gave to Giáp–second to Nguyễn Tường Tam at the conference–a letter addressed to Hồ, which read:

The New France does not intend to dominate Indochina. But she wants to be present there. She does not consider her work done yet. She refuses to abdicate her cultural mission. She feels that only she can regulate and coordinate technology, economy, diplomacy and defense.

Finally she will preserve the moral and material interests of the nationals.

All this within respect of the national traits and with the active and friendly participation of the Indochinese people.

Dalat, April 5, 1946 (5)

Words in this letter were persistent, disdainful, and arrogant. But Hồ did not seem to care. He continued to send another delegation to France and got involved himself in the last phase of the Fontainebleau Independence Talks. Prior to his departure, Hồ ordered his legal collaborators in Hanoi, Huế and Saigon to liquidate all nationalist parties’ leaders and members who had cooperated with the communists in the coalition government in the National Assembly and at all regional levels. Other classes of intellectuals and sects’ leaders were included.

Tens of thousands of non communist people were killed in this communist second phase of mass butchery. Nguyễn Hải Thần, Huỳnh Thúc Kháng, Nguyễn Tường Tam and Vũ Hồng Khanh fled to China. Those who escaped the communist purge had few choices: to disperse and regroup their parties later on or to turn to the French.

The armed forces of the VNQDD were broken into pieces by the French forces of General Jean Etienne Valuy. By the end of October, Valuy had established a series of garrisons and outposts on the Sino-Vietnamese border and along colonial route #4 from Cao Bằng to Lạng Sơn and Lào Kay in North Vietnam. On November 26, 1946, his forces suddenly bombarded, attacked and seized the seaport of Hải Phòng. The fighting moved to Hanoi. On the night of December 19, Giáp ordered the Việt Minh forces to launch an attack on the French in Hanoi and Hồ returned to Pắc Bó to begin the “long war of resistance” against the French. The First Vietnam War had exploded.

In the next eight years, the French not only faced the Việt Minh on the military front, but also the Vietnamese nationalists on the political and diplomatic fronts and finally with their uneasy ally–the Americans on the political, diplomatic and economic fronts.

On the military front, the French had the upper hand over the Việt Minh throughout Vietnam from South to North from September 1945 to December 1949. In North Vietnam from November 7 to 22, 1947, General Valuy conducted the Lee operation in Việt Bắc with an operational force of 20 battalions. His paratrooper units almost captured Hồ and Giáp in Bắc Kạn or Chợ Mới. The Việt Minh forces suffered 9,500 casualties and many of their supply depots were destroyed.

However, once the Red Army–Hồng Quân–of Mao Tse-tung had defeated and pushed the Nationalist Army of Chang Kai-shek to Formosa (December 7, 1949) and Mao established the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in mainland China on October 1st, 1949, the French had lost any hope to win the war in Vietnam. Mao offered to the People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN) of Giáp safe sanctuaries in several provinces bordering North Vietnam. There, Giáp’s large units could be trained, armed and supplied by the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA). Mao also ordered the formation of two important groups to help and supervise Ho’s communist party and Giap’s army: the Chinese Political Advisory Group (CPAG) and the Chinese Military Advisory Group (CMAG). These two groups arrived at Giap’s headquarters at Quảng Uyên in Việt Bắc on August 12, 1950 and Chinese advisory groups were assigned to all levels of Giáp’s army. (6) The PAVN thus became the first armed forces in Vietnam to have foreign advisors at its headquarters and combat units–more than a decade before the army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN). In the 1960’s, the number of these Chinese political, military advisors, specialists and technicians grew to more than 300,000 men in North Vietnam. The famous Chinese General Chen Geng–Trần Canh–assigned to Giáp’s headquarters was ready for the Việt Minh’s first offensive campaign.

– After losing base camp Đông Khê and two large forces sent from Lạng Sơn and Cao Bằng to rescue it, French General Marcel Carpentier ordered the abandonment of French garrisons and base camps along the Sino-Vietnamese border. Việt Bắc had completely fallen to the Việt Minh. The French switched back to the defensive mode. In December, General de Lattre de Tassigny arrived in Saigon as High Commissioner in Indochina and commander-in-chief of French forces. He immediately ordered the establishment of a defensive system– de Lattre Line–to protect Hanoi, Hải Phòng and several populous and wealthy provinces in the Red River delta. The general expected to defeat the communists in Vietnam in fifteen months and “save it from Peking and Moscow.” (7) But he failed and died of cancer on November 20, 1951.

-On January 13, 1951, Giáp launched the second offensive campaign targeting the Red River delta and the de Lattre line. His forces suffered huge losses in Vĩnh Yên and Mao Khê when de Lattre counterattacked with napalm bombs and paratrooper units. However, Giáp was able to maintain more than three divisions in the delta and conducted several large attacks on French positions in Phú Lý, Ninh Bình, Nam Định and Phát Diệm, etc… within the de Lattre line.

-On October 24, 1952, Giáp moved eight regiments to the northwest region of North Vietnam to attack French garrisons in Nghĩa Lộ, Sơn La and Lai Châu in order to pave the way for his large forces to invade Laos. French General Raoul Salan, who replaced de Lattre, conducted the Lorraine operation in Việt Bắc in November to prevent Giáp’s forces from entering Laos, but failed.

-In April 1953, three PAVN divisions were sent to Laos. In combination with small Pathet Lao units, these divisions waged war by attacking French positions in the south of Luang Prabang and in the Plain of Jars–Cánh Đồng Chum. In May, Paris appointed General Henri Navarre as commander-in chief of French forces in Indochina.

-In the summer of 1953, the communist party and the PAVN planned a winter-spring campaign (1953-1954) in the Red River delta and cancelled their campaign in Laos.

-On August 27 and 29, Beijing leaders sent two messages to Hồ through their CPAG’s senior advisor Luo Guibo. One of these read, “Eliminate the enemy in Lai Châu, liberate the northern and central parts of Laos, then expand the battleground to southern Laos and Cambodia to threaten Saigon.”(8)

-In mid-November 1953, Giáp sent two infantry divisions and part of an artillery division to Lai Châu to invade Laos. General Navarre promptly decided to occupy Điện Biên Phủ, a small valley village in a remote area straddling the crossroads between Vietnamese and Laotian borders some 188 miles west of Hanoi. He sent 10,000 troops to transform the valley into a strong garrison and serve as bait to entice Giáp’s troops in order to destroy them with his crack infantry and superior air power. He expected to confront Giáp’s two divisions but ended up facing four divisions with the most modern Chinese artillery guns.

-At 1700 hours on March 13, 1954, the Việt Minh began to attack Điện Biên Phủ. In the meantime, Giáp continued to send several divisions to wage war in Laos. But all eyes were concentrated on Điện Biên Phủ. Navarre had to reinforce the garrison with his last reserve of 5,000 paratroopers.

At the same time, on the political front, the French were dealing with South Vietnamese Nationalists who firmly demanded independence from France. After being crushed by the combined action of the French and the Viet Minh from July to November 1946, the Đồng Minh Hội had disintegrated, the VNQDD split off into five branches and the Đại Việt into four with their new leaders, being mostly intellectuals. (9) Meanwhile a dozen of newly formed political parties, associations and groups overly or secretly emerged in Hanoi, Hue, and Saigon and other large cities. While a small number of intellectuals cooperated with the French, in Nam Kỳ (South Vietnam) under the temporary government of Prime Minister Nguyễn Văn Thinh, the majority of Vietnamese intellectuals and nationalist parties’ leaders and members struggled for Vietnam’s reunification and independence.

-On February 17, 1947, leaders and members of several nationalist parties in exile formed the National United Front in Nanking, China–Mặt Trận Quốc Gia Thống Nhứt Toàn Quốc. It received participation from other nationalist parties’ leaders and intellectuals in the country.

-On March 17, 1947, the National United Front issued a manifesto advocating the return of former Emperor Bảo Đại and the creation of a Republic in Vietnam. Bảo Đại had abdicated his throne in September 1945 and was honored by Hồ as his “Supreme Advisor.” Six months later, on March 18, 1946, while leading a delegation to China, Bảo Đại sent his resignation to Hồ and remained in exile in Hong Kong.

-On September 9, 1947, the National United Front sent a delegation of 24 delegates to meet Bảo Đại and to present to him their manifesto. Notable figures in this delegation included Ngô Đình Diệm, Nguyễn Văn Sâm, Đinh Xuân Quảng, Nguyễn Tường Tam, Phan Quang Đán, Trần Văn Tuyên, and Trần Văn Lý (governor of central Vietnam).

-On May 27, 1948, Bảo Đại cabled to Saigon and appointed General Nguyễn Văn Xuân as prime minister.

-On June 5, 1948, Prime Minister Nguyễn Văn Xuân, as Bảo Đại’s official delegate, signed with French High commissioner in Indochina–Cao Ủy Đông Dương–Emile Bollaert the “Ha Long Agreement” on the reunification and independence for Vietnam in the presence of Bảo Đại.

-On March 8, 1949, Bảo Đại signed with French President Vincent Auriol the “Elysée Agreement” concerning the formation of a Vietnamese National Army, a self-governing foreign affairs and domestic affairs.

-On June 13, 1949, Bảo Đại returned to Vietnam as Chief of State and formed the first cabinet of the Republic of Vietnam with himself as prime minister and Nguyễn Văn Xuân as deputy prime minister and defense minister. The Elysée Agreement was ratified by the French National Assembly on January 29, 1950. Though France “yielded control of neither Vietnam’s army nor its foreign relations,” the U.S. began to view the Bảo Đại solution with greater sense of urgency.(10)

-On February 7, 1950, the U.S. formally recognized the Republic of Vietnam. Britain and Australia also recognized Vietnam as an associate state within the French Union. In the following months, Vietnam became a member of six United Nations’ specialized agencies and was recognized by 37 other nations in the free world.

The political lines were finally drawn within Vietnam. Hồ with his DRV was recognized by the communist bloc and Bảo Đại with the Republic of Vietnam or Government of Vietnam (GVN) by the free world.

However, both Hồ and Bảo Đại were deceived by the new French colonialists. With the temporary March 6, 1946 Agreement, they could join forces with the Việt Minh to pacify North Vietnam and eliminate nationalist parties–particularly the VNQDD and its armed force, which had been supported by the nationalist forces of Chang Kei-shek. Then with the Elysée Agreement, they could use Bảo Đại’s government and army to fight the Việt Minh. Indeed after the formation of the Army of Vietnam (ARVN) from May 1951 to December 1953, all Vietnamese units from battalion-size were placed under the command of French forces to fight the war. Even in May 1952, when the ARVN had a Joint General Staff, the French promoted a Vietnamese-born-French Air force colonel, Nguyen Văn Hinh to Lt General and commander-in-chief of the ARVN. After appointing four consecutive prime ministers (Nguyễn Phan Long, Trần Văn Hữu, Nguyễn Văn Tâm, and Bữu Lộc) to deal with the French, Bảo Đại left Vietnam and returned to France. He finally offered Ngô Đình Diệm the post of Prime Minister, which Diệm accepted with the backing of the U.S.

Finally, the most dangerous opponents the French had to face in Vietnam were their uneasy ally, the Americans.

U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt had his own view on colonialism. On many occasions, he refused to help the French to fight the Japanese and attempted to push France out of its colonies. After the end of WWII, the U.S. changed its policy in Indochina. President Harry S. Truman ordered all Americans and two OSS intelligence teams out of Vietnam. With the application of the “Truman Doctrine and Marshall’s Plan” and the “Deterrence Strategy,” Truman considered the cooperation of Great Britain and France in Europe vital for the U.S. to meet the growing Soviet threat. In May and June 1945, French Foreign Affairs Georges Bidault was informed that he U.S. would not interfere with French foreign policy towards its colonies in Indochina. France reluctantly accepted the Marshall plan to rebuild western European countries including West Germany.

In Indochina, the FEF’s pacification operations to reoccupy their old colonies progressed favorably until the end of 1949. But, by January 1950 after Mao had established the PRC in mainland China, supported North Korean Army in its invasion of South Korea, and transformed Việt Minh’s small units into a well trained army in sanctuaries along the Sino-Vietnamese borders, the U.S. had a different view of French role in Orient.

-On May 1st, 1950, Truman approved US$10 million for urgently needed war materials for the French in Indochina.

-In July 1950, French authorities in Saigon unwillingly welcomed the arrival of the U.S. Military Assistance Advisory Group-Indochina (MAAG-I) led by Brigadier General Francis G. Brink. By the end of 1950, U.S. military aid to Indochina rose to US$100 millions after French General Carpentier lost Việt Bắc in September 1950, particularly after more than 300,000 Red Chinese troops fought alongside the North Korean Army.

Communist China’s threat became clear in East and Southeast Asia, especially in Vietnam. By providing military aid to French forces in Indochina, the U.S. began to commit itself to the war in Vietnam. The fighting in Vietnam was seen in a new light–transforming it from a colonial war into an anti-communist war; and the FEF was seen as a force fighting “a mandate war” (một cuộc chiến ủy nhiệm) for the United States. French leaders knew of this concealment but they thought they could win the war by exploiting American aid. Since then, divergence, misunderstanding and discredit had silently emerged between these two allies at every echelon. The wise and prominent General de Lattre de Tassigny once openly declared, “In our universe, and especially in our world today, there can be no nation absolutely independent. There are only fruitful interdependencies and harmful dependencies…” However, after his death, it became clear the French could not win the war when, supported by Red China, several Viet Minh divisions came up to Lai Châu in December 1952 and waged war in Laos in April 1953. Laos then became an important strategic arena receiving attention from both Beijing and Washington.

-In March 1953, French Prime Minister René Mayer, minister of Foreign Affairs Georges Bidault and minister of the Associated States of Indochina Jean Letourneau came to Washington to ask for additional military aid for Indochina. They were granted US$385 million. By the end of 1952, the US had paid 40% of the US$700 million French war’s cost in Vietnam. The French were recommended to send two divisions to Vietnam, draw pacification plans to win the war, and develop the Army of Vietnam. Returning to Vietnam, Letourneau drew the so called “Letourneau plan.” He did nothing with his plan, but displayed his “super king’s power” over the real kings of Indochina. In mid-November 1953, Giáp sent three divisions to invade Laos and four other divisions to attack the French at Điện Biên Phủ. Within two weeks, the garrison was cut off from the rest of the world, except for unreliable parachute supplies.

-On April 1954, President Dwight D. Eisenhower in a speech to Congress declared that the loss to Indochina would cause the fall of Southeast Asia like “a set of dominoes.”(12) In the meantime, the Pentagon formulated a massive bombing scenario under the code name “Operation Guernica Vulture” to save Điện Biên Phủ. However, relying on U.S. Congress’ indecision, the advice of the Army’s Chief of Staff, and Great Britain’s opposition to such a perilous intervention, Eisenhower refused to consider a military commitment to Indochina, cancelled the Guernica Vulture operation and abandoned the French to their own fate. Once the U.S. had made its decision, Điện Biên Phủ fell. When the Viet Minh violently attacked the central command of the garrison, its commander, Brigadier General de Castries was ordered by General Navarre to surrender to the enemy at 1700 hours on May 7, 1954.

-On May 8, 1954 at the Geneva Convention, a political solution for Vietnam was negotiated. A temporary partition of Vietnam was to be created and on July 20 at 2400 hours, the Geneva Accords were signed between French Brigadier General Henri Delteil and DRV’s deputy minister of defense Tạ Quang Bữu. Delegates of Great Britain, the USSR, Cambodia, and Laos signed the accords while the U.S. and the State of Vietnam refused to sign. The 17th parallel became the border between the communist North and the Republican South.

By the time the war came to an end in July 1954, the U.S. had paid to the French US$1 billion for war expenditures in Indochina and another billion through the Marshall Plan for economic aid and reconstruction of France. The French were the big losers. They not only had to pull out of North Vietnam, but also had to leave South Vietnam a year later under the aggressive demand of Prime Minister Ngô Đình Diệm and U.S. pressure.

General Navarre claimed that the U.S. should not have abandoned Điện Biên Phủ. Had it intervened, it would not have had to become involved later in the Vietnam war. However, the U.S. could not let South Vietnam and the rest of Indochina fall into the hands of the communists. Eisenhower had combined Roosevelt’s and Truman’s policies: “termination of French role in Indochina by whatever means” and “containment of communist expansion” in Southeast Asia and crystallized these into a new one: “Replacing the French in Indochina and holding it.”(13)

Later, De Gaulle warned Eisenhower’s successor, “The ideology that you invoke will not change anything…You Americans wanted, yesterday, to take our place in Indochina. You want to assure a succession, to rekindle a war that we have ended. I predict to you that, step by step, you will be sucked into a bottomless military and political quagmire.” (14) This statement from the French President was not only a warning, but also an expression of resentment and anger against the U.S. government. Relationship between the two governments had not been smooth since the end of the first Vietnam War.

I would like to apologize for keeping you too long with details about the First Vietnam War. But the latter teaches us many lessons. It is like a Pandora box which lures people with its charming appearance but contains every sin, misery and misfortune. Indeed, behind every beautiful word is hidden a device that would lead to catastrophe or death.

A day after declaring “independence” in 1945, Hồ ordered the killing of tens of thousands of people. A week after forming a “coalition government” with leaders of nationalist parties (March 3, 1946), Hồ signed with Sainteny a temporary agreement on March 6 and joined forces with the French to annihilate other nationalist parties and massacre their leaders (July-October 1946). More than 40,000 people lost their lives in this second phase of communist mass killing. The Vietnamese communists had never tolerated intellectuals who did not work for them, especially those who were well known; Phạm Quỳnh, Huỳnh Phú Sổ, Nguyễn An Ninh were the examples. Many who fought within the Viet Minh ranks were not communists. They were neither mesmerized by Hồ’s oratory or hypnotic qualities nor overwhelmed by communists’ propaganda catch phrases, but by threats of death or ” isolation” of themselves and their families. These practices will emerge with more ferocity in the next phase of the war.

From the French, we have learned that their beautiful terms such as “independence,” “free state,” “agreement” have no value but only conceal schemes of bondage, compulsion, and deception. By signing agreements with Hồ, they were able to move troops to North Vietnam. By signing the Ha Long and Elysée agreements, they could temporarily solve chaotic political problems and demand more military aid from the U.S.

We have learned little from the U.S. in the First Vietnam War. The biggest lesson the U.S. had learned was that the “abandonment” of the Chinese Nationalist Army of Chang Kei-shek led to the loss of mainland China to Mao’s communists. After the Japanese surrendered on August 14, 1945, civil war between these forces renewed immediately. As commander of the U.S. “China Theater” and Chief of Staff of Chang Kei-shek, General Albert C. Wedemeyer successfully helped to reorganize Chang’s troops into a well trained and well equipped army and provided sea and airlift to move the 500,000 troops to north and central China.(15) The outcome of the war looked bright for the Nationalist Army in these regions.

-In August 1945, U.S. Ambassador to China Patrick J. Hurley personally escorted Mao to Chung King (Trùng Khánh) to meet Chang for a peace talk. But the conference broke down and the Ambassador resigned. Returning to America, he blamed his failure on the “destructive efforts of pro-communist American Foreign Service Officers.”(16)

-On December 14, 1945, Truman sent General George C. Marshall to China as his personal representative with full powers to mediate the dispute between Mao and Chang. Under pressure, Chang and Mao signed an agreement in February 1946 to unify their main forces into one national army of 50 divisions (40 nationalist and 10 communist). The agreement broke down within a few weeks after Soviet forces leaving Manchuria left all captured Japanese military equipment to the Chinese communists–enough to equip the entire communist army of Mao.

The war broadened violently and Chang’s forces pushed Mao’s forces back to their strongholds in North China. Chang’s offensive campaigns were successful from March to July 1946.

-On July 29, 1946, Marshall “annoyed by the nationalist offensive and under strong communist propaganda against U.S. assistance to the Nationalists, ordered an embargo on all U.S. military supplies to both sides. This actually only affected the Nationalist army since the communists had received captured Japanese military equipment.”(17)

-In September 1946, U.S. Marines and other large combat units began withdrawing from China. This was further interpreted as a U.S. abandonment of the Nationalist government. On November 8, Chang informed General Marshall about his willingness to talk to Mao on peace. The communists rejected Chang’s overture and Marshall’s mediation.

-On January 6, 1947, Marshall reported the failure of his peace missions and was recalled to Washington. A contingent of 12,000 US Marines were also ordered to withdraw from China. Since October 1947, the communist army regained its ability on the battlefield. Elsewhere in Manchuria, North and central China, they held the initiative. Since November 1948, many field armies of Chang had desperately fought without supplies and ammunitions. In two years (October 1947-August 1949), Chang suffered the consecutive losses of many large provinces in North and central China, the northern bank of the Yangtze River, including Peking.

-In February 1949, the last U.S. 3rd Marine Regiment in China was ordered back to America, confirming the abandonment of the Nationalist government. On April 20, two field armies of Mao crossed the Yangtze River and captured Nanking two days later.

-On August 5, 1949, the fatal coup came when the U.S. State Department issued the “White Paper” criticizing the Nationalist government of Chang and formally cutting off further military aid. (18) The rest of mainland China fell to the communists a few months later.

-On December 7, Chang’s government and remaining troops completed their withdrawal to Formosa. Although the U.S. resumed economic and military assistance to Chang’s government, it was too late, Mao and his CCP had established a rigid totalitarian communist regime in mainland China. Their socialist revolution had smashed the four-thousand year-old Confucian society. In foreign affairs, Mao’s ambition was clear, “We must by all means seize Southeast Asia including Vietnam, Thailand, Burma, Malaysia and Singapore.”(19)

Thus the U.S. greatest strategist Marshall who had “been annoyed” in 1946 by Chang’s temporary victories over the communists contributed a great part to the loss of mainland China to the communists in 1949. Since that time, Red China has been a dangerous threat to its neighbors and the U.S.

Sometimes, I wonder how much the U.S. has learned from its policies of “supporting and abandoning its ally?” Had the U.S. not abandoned Chang’s army, China would not have turned red and the First Vietnam War would not have happened. Or at least, France would have easily controlled the Viet Minh. Had the U.S. continued to support France at Điện Biên Phủ, there would not have been a second Vietnam War. And the three Indochinese countries would have changed differently, perhaps with less bloodshed, destruction and resentment.

LESSONS LEARNED FROM THE PERIOD OF CONSOLIDATION AND THE SECOND VIETNAM WAR

There was a period of nine years (October 1954-Oct 1963) during which the DRV and the Republic of Vietnam (RVN) consolidated their regimes. It could be called the “Ethical War between North and South.” Indeed, immorality and morality were the characteristic features of the northern and southern doctrines of the time.

In North Vietnam, Hồ and leaders of the communist party, strongly supported by the Soviet Union and Red China, erected their totalitarian regime with extreme ferocity and immorality. After the Viet Minh’s take-over of Hanoi in mid-October 1954 and while the exodus of one million people was not yet completed, Hồ and other leaders of the VWP immediately formulated a new strategy “to consolidate the North and to aim for the South” (cũng cố miền Bắc và chiếu cố miền Nam).

To consolidate the North, Hồ strengthened the internal organization of the party, the government and the people’s army by purging possible reactionaries; established a “parallel hierarchy” from the top down to all executive and administrative levels and in the army; created organizations to control personnel at all levels. Other organizations were also created to control all the Vietnamese people, such as the Mặt Trận Liên Việt–the National United Front, which was composed of youth groups, farmers, workers, war veterans, and other associations. The “Social Socialist reform” was strictly executed as we have learned in the first part of the paper. These audacious measures transformed every wealthy person into an empty-handed man, every store owner into a tax debtor and any intellectual into a prisoner for life. All of French’s former employees, officers, soldiers and influential people, who for whatever reason could not migrate to South Vietnam during the 300-day “official evacuation” from August 1954 to May 1955, were silently sent to isolated reeducation camps in forested areas in Tây Bắc and Việt Bắc. Their families were forced to relocate to remote new economic zones. It was estimated that about 300,000 people were forced to leave Hanoi and other cities and towns to endure a harsh and miserable life. The number of those who were secretly liquidated was unknown. However, the most horrible crime committed by Hồ and his men was the “land reform.”

The Land Reform program was adopted from Mao’s. Hồ formally applied the first campaign in 1953-1954 in Việt Bắc. This campaign was premature as the VWP controlled only half of North Vietnam’s territory. Decrees were issued to reclassify peasants into five classes: landlords, rich farmers, medium farmers, poor peasants, and laborers. Landlords were further classified into three categories: 1) traitors, reactionaries, and cruel landlords; 2) ordinary landlords; 3) resistance landlords or those who participated in the resistance against the French (1949-1954). Trường Chinh, Secretary General of the VWP, was named President of the Land Reform Central Committee. He sent his expert cadres, who had learned the procedures from the Chinese to experimental sites to lead poor and landless peasants (bần cố nông) in enacting the reform. The reform was inhumane because the landlord was arrested, treated like a mad dog, then badly tortured before being dragged to an open area to be denounced for any imaginary crime by the mass. If sentenced to death, he was immediately shot after the trial. The process was also immoral since the crime-denouncer, who had been selected and coached in advance by the cadres, would be a son, daughter, sibling or relative of the “criminal.” Properties of the condemned landlord were then confiscated.

The most atrocious policies of the land reform were its “isolation” and “connection.” Isolation meant that family members of the condemned landlord were isolated in his home and forbidden to leave for any reason, to work or purchase food. The period lasted three or four months. As a result, most of the victims died by starvation, children and elderly first. Connection meant that those related to the condemned landlord were punished like the landlord or isolated with their family members. Resistance landlords were similarly punished like the other landlords.

The land reform campaign, which started on March 11, 1955 was cancelled by Hồ in March 1956 when the number of victims rose to 500,000 or more. (21) Võ Nguyên Giáp was assigned to rectify the program through the so-called “Rectification of Errors campaigns.” Although Trường Chinh was dismissed from his position, he was not disciplined. The reform campaign and the purge of reactionaries in cities and towns ignited violent peasant revolts in Nam Định, Ninh Bình, Nam Đàn and Quỳnh Lưu. These revolts were bloodily suppressed by the people’s army, which killed or executed thousands of peasants. While coverage of the land reform’s revolts was minimal, the literary revolt of intellectuals and men of letters in Hanoi was known in several Asian and European countries. The real cause of this revolt was the VWP’s humiliation and oppression of intellectuals combined with the purge of nationalists, reactionaries and landowners.

The literary revolt started in Hanoi in February 1956 with the appearance of “Giải Phẩm Mùa Xuân,” or the “Spring Selection of Literary Pieces” from a group of talented composers, artists, writers, and poets. The short poem Mr. Lime Pot compared the aging Hồ–who had become more cruel and less discerning as years passed by–to a lime pot, the opening of which narrowed day by day by the accumulation of dehydrated lime. The author was Lê Đạt, a cadre of the Center for Propaganda and Training Directorate (Cục Tuyên Huấn Trung Ưong). The other two editors of the Giải Phẩm were poet Hoàng Cầm and poet and composer Văn Cao. The other contributors were notable writers and poets in North Vietnam. All of them had participated in the resistance against the French. The 500 verse- poem by Trần Dần entitled Nhất Định Thắng (To win at all cost) hinted that Hồ had stabbed people in the back during his commitment to cut Vietnam in half. This led to the migration of one million people to the South transforming Hanoi into a sullen and oppressive place drowned by a multitude of red flags. In the following issues of the Giải Phẩm, other writers people contributed many anti-regime articles. They included Nguyễn Hữu Đang, former Hồ’s intimate and DRVN’s deputy minister of propaganda; Professor Trương Tửu, a Marxist critic; Professor Đào Duy Anh, a notable scholar and lexicographer; Professor Trần Đức Thảo, a philosopher who taught for a time at the Sorbonne in Paris; and Phan Khôi, an advanced Confucian scholar, journalist, writer, and poet. Phan Khôi was also the editor of the Bán Nguyệt San Nhân Văn–biweekly Humanities–the first issue appearing in Hanoi on September 15, 1956. Nhân Văn and Giải Phẩm became the anti-regime literary movement.

The Nhân Văn contained more political articles than the Giải Phẩm, although both papers revealed the dark side of an unjust communist society. They attacked the VWP leaders of corruption and nepotism and the communist regime for its atrocities and totalitarianism. All issues of Giải Phẩm and Nhân Văn were warmly received by the public. In a short fiction, Trần Duy described the VWP leaders as “giants without heart.” Như Mai insinuated that the VWP literary cadres who wrote with the monotonous style of Tô Hữu–director of the Center of Propaganda and Training directorate–were “robot poets.” Phùng Cùng alluded that every faded talent such as Nguyễn Đình Thi, Huy Cận, Huy Thông, Xuân Diệu, Nguyễn Công Hoan, Nguyễn Tuân, and so on…was like the “old horse of Lord Trịnh.”

Reactions to these literary cadres was firm. Professor Nguyễn Mạnh Tường–who had obtained a double doctorate degree in laws and letters in Paris at the age of 22 and returned to Vietnam to serve the DRVN under the direct appeal of Hồ–gave a speech against the VWP’s policy and pledged more individual freedom and the return of the rule of law. He was also considered a reactionary of the Nhân Văn and Giải Phẩm movement. The latter lasted until December 1956 when Hanoi students became involved in the revolt with the publication of Đất Mới–the New Land magazine. The VWP took immediate action by seizing all issues of the magazine. Hồ signed a decree on December 9, 1956, banning freedom of press. On December 15, the VWP ordered the closing of the Nhân Văn and Giải Phẩm magazines. The literary movement had come to an end. All founders, contributors, supporters and anyone who had any connection with the magazines were expulsed from the associations, sent to remote labor camps or taken into custody. Trần Đức Thảo and Nguyễn Mạnh Tường who had come back from France to serve the Hanoi government were sent to reeducation camps and spent the rest of their lives in miserable condition. The majority of people arrested were students; many never returned home and others committed suicide. Thereafter, the VWP regained control of all arts and letters associations and activities.

With the purge of all “internal enemies” who belonged to the classes of intellectuals, capitalists, and landowners within the party, government, Hồ and the VWP took total control of the population and consolidated the bases of a socialist society in North Vietnam. By the end of 1960, they began to strategize their conquest of the South.

The biggest lesson we have learned was that these “giants without hearts” had won the war against their people in North Vietnam not by winning their “hearts and minds” but by their inhumane and immoral oppression. We have also learned that these giants never tolerated intellectuals who opposed them on any political issue and always considered them as “internal enemies” simply because they were intellectuals. Nowadays, overseas intellectuals wishing to serve the giants have to learn more about the cases of Professors Trần Đức Thảo and Nguyễn Mạnh Tường.

In South Vietnam, Prime Minister Ngô Đình Diệm when facing with the severe social, military and political impacts of the post division turbulent period, always maintained his wisdom and toughness in order to solve problems. His dominance was clearly shown by his ethical behavior and his natural leadership.

In the social domain, with the aid of U.S. Colonel Landsdale–his advisor–Diệm received nearly one million refugees from North Vietnam with benevolence. Refugees–79 percent Catholics, 11 percent Buddhists, and 10 percent others–were resettled in several large cities or fertile lands in the Mekong delta according to their classes or careers. However, they were free to choose the means to rebuild their lives. People who had lived in Hanoi were resettled in Saigon, Gia Định, Gò Vấp or Biên Hòa. Each family received an allowance of 800-1000 đồng (about $US300). Families resettling in the provinces–for example in Nha Trang–were given one house per family. The United States in 1955 and 1956 contributed more than $US129 million to the refugees. Those who wanted to further their studies could go back to school and apply for jobs in government’s organizations or private businesses. Schooling was free for children.

In just a few years, these northern refugees began contributing to the consolidation of the first free political regime in the South, the development of the army and the building of South Vietnam. New literary pieces were written by Doãn Quốc Sĩ, Dương Nghiễm Mâu, Mai Thảo, Nguyễn Mạnh Côn, Thảo Trường, Nguyên Sa, Cung Trầm Tưởng, Thanh Tâm Tuyền and so on…

In the military domain, after the 1954 Geneva Accords went into effect, the French who withdrew completely from North Vietnam wanted to remain in South Vietnam. General Paul Ely became High Commissioner in Indochina and FEF’s Commander-in-chief. Lt. Colonel Nguyễn Văn Hinh–a naturalized Frenchman–was promoted Lt. General and made Chief of Staff of the South Vietnamese National Army. Diệm asked Bảo Đại–who lived in France–to release General Hinh and transfer the National Army to the Saigon government. Under pressure from Washington, the French withdrew from Vietnam in April 1956 allowing Diệm to realize his plans of reuniting the different nationalist forces into a unique army. The first military campaign to sweep the Bình Xuyên forces out of Saigon was successfully accomplished by the end of April. In the following months, two other Cao Đài and Hòa Hảo armed forces were also pacified and their soldiers were integrated into the National Army (ARVN). With the help of Lt. General Samuel Williams, U.S. MAAG’s Commander, Diệm by December 1956 transformed the ARVN into a force–eight divisions–capable of withstanding a North Vietnamese invasion long enough to allow U.S. intervention within the framework of SEATO (Southeast Asia Treaty Organization). From 1956 to the end of 1960, in conjunction with the strategic hamlets’ program, the ARVN had neutralized 16,000 Việt Minh cadres who had remained in South Vietnam. South Vietnamese territory from the demilitarized zone on the southern bank of the Bến Hải River to the point of Camau was controlled by that army.

On the political arena, ten days before Ho’s troops entered Hanoi to take control of North Vietnam from the French, President Eisenhower sent a letter to Prime Minister Diệm expressing his willingness “to assist the Government of Vietnam in developing and maintaining a strong, viable state capable of resisting attempted subversion or aggression through military means…”(22) It was clear that the U.S. supported South Vietnam against any communist aggression. Diệm was then elected President in October 1955. In March 1956, 123 members were elected to the Congress under a Republican constitution. A regime based on democracy and “spiritual Personalism” began.

One might want to compare the two dogmatic doctrines of two leaders of North and South Vietnam.

Hồ turned out to be an atrociously evil leader who consolidated his power in the North and transformed it into a socialist society. Communism, which highlighted the proletariat behave like an absolute dictatorship with Hồ appearing like an image of death holding a sickle.

Diệm was a virtuous moralist and leader who molded the South with benevolence and morality. “Spiritual Personalism” (Chủ Thuyết Cần Lao Nhân Vị) was a philosophy applicable to the building of a better humane society. It emphasized the dignity of human beings or humanism which contrasted with communism. This political and social philosophy was, however, unknown to political makers in Washington and South Vietnam. Only members of the Spiritual Personalist Party (Đảng Cần Lao Nhân Vị) who assembled around President Diệm’s brothers—Adviser Ngô Đình Nhu in Saigon, Monsignor Ngô Đình Thục in the Mekong Delta, Ngô Đình Cẩn in Huế–would know its doctrinal dogmas and perhaps only intellectuals within the party would know how to combine these doctrines with democratic practices. As a result, only a small group of people was handling national power for years causing problems for Diệm and his family. The regime was accused of autocracy, nepotism, corruption, and anti-Buddhism that led to the November 1960 and 1963 coups d’état. The second coup disrupted the First Republic killing President Diệm and his brother Nhu.

The biggest lesson we have learned from that period of consolidation was the propaganda and the ethics in politics. In North Vietnam, Hồ and the VWP’s leaders were expert in appealing to patriotism, national pride, and traditional xenophobia to lure people into a war against “white invaders” and their puppets. On the other hand, they forced the populace to do whatever they wanted with their atrocious measures. The lack of propaganda in the South would topple the democratic regime and cost the lives of President Diệm and his brother Nhu. Sometimes, I wonder why Nhu, the erudite strategist of South Vietnam, did not spread the dogmas of Spiritual Personalism widely into the populace, but secretly kept them with members of the party? Why did Diệm not explain clearly these dogmas to his supporters in Washington and suggest the use of Personalism as the main theory for confronting Communism? Although Washington misunderstood or did not understand Diệm’s philosophy, I personally appreciate his morality in politics and adore his dignity as a true leader of Vietnam. He lives eternally in our hearts and minds.

The Second Vietnam War has taught us many valuable lessons and clarified some paradoxes. One of the mysteries of U.S. foreign policy toward Vietnam, Southeast Asia and China during that period has rekindled numerous debates, discussions, and symposia for decades after the war’s end. Although international historians, observers, politicians and strategists have dissected American strategies and policies of U.S. Presidents, no satisfactory answer has emerged. The answer rests in the study of U.S. policies toward Red China, which was the key that unlocked the war. Vietnamese authors have written thousands of pages on this subject. I have devoted 200 pages of my 270-page book on this matter. In this paper, I would like to just make a few remarks.

American foreign policy was based on containing Chinese communist aggression. The U.S. took the lead in forming an anti-communist regional organization: SEATO, which comprised Australia, New Zealand, Indonesia, Thailand, the Philippines, France, United Kingdom, and the US. South Vietnam being the front line of deterrence against the communists was strongly supported by the Eisenhower administration. The objectives were “to prevent North Vietnam from overthrowing the anti-communist Saigon regime and to allow the South Vietnamese to live in freedom under a government of their choice.” The stability and growth of South Vietnam during the Eisenhower’s period demonstrated the success of his foreign policy. From 1955 to 1960, President Diệm had reestablished order over a fractional and chaotic South Vietnam and consolidated it into a republican constitutional nation.

Unfortunately, the situation dramatically changed under the Kennedy administration, which wanted to transform this anti-communist fortress into a testing ground for a counter-insurgency war. This led to a “military escalation” in South Vietnam as the new president declared on a press conference in May 5, 1961 that the U.S. might consider the use of forces if necessary to help South Vietnam resist communist pressure. (24) Diệm and Nhu let the U.S. Ambassador in Saigon unambiguously know that the “people of South Vietnam did not want U.S. combat troops.” (25) In spite of their opposition, counterinsurgency was applied in South Vietnam. MAAG changed into MACV (Military Assistance Command Vietnam). The “Eagle flights”–first helicopter units were dispatched to South Vietnam. The Green Beret Corps was organized and several large units were sent to central Vietnam to train South Vietnamese Special Forces and to carry secret missions in North Vietnam and Laos.

The “Eleven Point Program” was signed between Saigon and Washington on January 2, 1962 to implement pacification plans in the central highlands and the Mekong Delta. On February 15, 1962, Senator Robert F. Kennedy said,

“We are going to win in Vietnam; we will remain there until we do win.” (26).

American military advisors in South Vietnam increased from 900 to more than 22,000 by the end of 1962. Although the “Eleven Point Program” was excellent, committing combat troops to South Vietnam was Kennedy’s first big mistake. His second mistake was to neutralize Laos. According to Averell Harriman, the U.S. should keep the Laotian Royal Force to safeguard Louang Prabang and Vientiane and concede the eastern part of Laos to the communist Pathet-Lao. The January 23, 1962 Geneva Accords, which benefited the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) allowed it to develop the Hồ Chí Minh trail in order to infiltrate and transport supplies and war equipment to South Vietnam. At least 35,000 men and women of the NVN 559th Special Group were placed under the command of Colonels Võ Bầm and Đồng Sĩ Nguyên to develop the trail. Had the trail not existed, the Second Vietnam War would not have existed in South Vietnam.

However, Kennedy’s biggest mistake was his arbitrary and brutal handling of the South Vietnamese leadership and his allowing ARVN generals to foment a coup d’état that killed Diệm and Nhu. President Diệm was the last strong leader South Vietnam ever had. His death became a tragedy for South Vietnam as well as for the United States.

Three weeks later, Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas. New President Lyndon Johnson inherited his predecessor’s legacy along with several problems:

1) the tacit war in Laos, which resulted from the 1962 Geneva Accords,

2) the Harriman line in Laos that allowed North Vietnam to exploit and develop the trail;

3) the chaotic, political, and economic situation and the anarchy in Saigon;

4) the U.S. military engagement in South Vietnam.

While in South Vietnam, the arc of communist insurgency approached closer to Saigon and several cities in the central highlands and central Vietnam, in Washington, Johnson faced the painful reality of reconciling his Vietnam’s nightmare with his dream of a “greater society” in America. He was determined to handle both issues at the same time.

Johnson continued Kennedy’s strategy by maintaining almost all of Kennedy’s team of advisers who had formulated war strategies for Vietnam. These politicians and bureaucrats, known as the “lunch bunch powers,” soon devised strategies and tactics for South and North Vietnam and Laos. North Vietnam continued to send tens of thousands of troops through the trail while in Saigon, the struggle for national power continued with several coups d’état between generals. The French derisively called it “La Guerre des Capitaines”–the War of the Captains. In such a chaotic situation, the U.S. carried out the strategy of “high profile defensive war,” which meant more combat troops to protect the DMZ, important seaports and airports. After the Maddox crisis produced the Gulf of Tonkin resolution (August 7, 1964), the Second Vietnam War really exploded with the first American air campaign “Operation Plan 37-64” bombing against North Vietnam. MACV commander, General William Westmoreland argued that the bombing of North Vietnam would not be enough. Since Hanoi would logically retaliate in South Vietnam, he requested more combat troops for the battlefield. However, the war Westmoreland wanted was not in South Vietnam, but in the southern part of Laos. In early 1966, he sent his plans to Washington with the main goal of repairing and developing the international highway 9 from Quảng Trị in central Vietnam through the central part of the Laotian panhandle to Savannaket on the east bank of the Mekong River. This Westmoreland’s line would be held by a U.S. corps-sized unit, which would block the Hồ Chi Minh trail and become the front line war. Westmoreland’s proposal was supported by U.S. Ambassador Ellsworth Bunker. Unfortunately, it was rejected by the “lunch bunch powers.” Later Bunker disclosed,

“Shortly after I arrived, I sent a message to the President urging that we go into Laos. If we cut the trail, the Viet Cong, I thought, would wither on the wine. What kept them going were supplies, weapons, and ammunitions from Hanoi.”(27)

Two years earlier, U.S. Admirals Grant Sharp and Thomas Moorer had respectively proposed to destroy the Nanning-Hanoi and Kumming-Hanoi railroads and to blockade Hải Phòng seaport to control supplies of war materials from Red China and the USSR. These proposals were also rejected.

As a result, the war could not be won by air campaigns alone with restricted objectives based on Washington’s “limited war” concept. Indeed, CIA and DIA (Defense Intelligence Agency of the U.S. Department of Defense) had concluded that the Rolling Thunder air campaigns against North Vietnam (March 1965-March 1968) and the Igloo-White, which targeted the Hồ Chi Minh trail, could not deter the flow of North Vietnamese manpower and supplies to South Vietnam. Consequently, Westmoreland had to fight a “Search and Destroy” mission within the boundaries of the South Vietnamese territory. NVA sanctuaries along Vietnamese- Laotian and Cambodian borders were left untouched. By the end of 1967, he had under his command more than 500,000 U.S. troops, 60,000 Allied combat units (Australia, New Zealand, South Korea, Thailand, the Philippines) and 500,000 South Vietnamese troops. With all these forces in hand, he still could not destroy NVA and VC divisions in South Vietnam. We know better what a limited war was and why the war could not be won under these circumstances.

Had the proposed Westmoreland’s line materialized and the Hồ Chí Minh trail cut, there would not have been a Khe Sanh and a Tết Offensive to defeat Johnson. And the Second Vietnam War would have been solved differently.

Then the best designs envisioned by the Johnson administration would have materialized for South Vietnam including the creation of Second Republic of Vietnam and the development of its armed forces. The ARVN became the RVNAF (Republic of Vietnam Armed Forces) on June 19, 1965. This armed forces later showed that it could fiercely face the strong and skillful NVA anytime and on any front. South Vietnamese people were deeply indebted to their armed force, which protected them and defeated the ferocious NVA in small or large battles during the Second Vietnam War until a fateful political solution disposed it from existence.

After Johnson turned down his party’s nomination for a second presidency, Americans began to oppose the long, costly and deadly war in Vietnam. The anti-war movements amplified their voices across America. General Frederic C. Weyand, former U.S. Army Chief of Staff, once stated,

“Vietnam was a reaffirmation of the particular relationship between the American Army and the American people. The American Army really is a people’s army in the sense that it belongs to the American people who take a jealous and proprietary interest in its involvement. When the Army is committed, the American people is committed; when the American people lose their commitment, it is futile to try to keep the Army’s commitment.”(28)

After the communist 1968 Tết Offensive, the American people lost their commitment. Thus, this important offensive should be considered as the turning point of the war.

1) Everywhere, during the first minutes of this offensive, surprise was complete. The most serious psychological event was the attack on the U.S. Embassy building that shocked Washington and caused more problems for South Vietnam despite the fact it was a suicidal strike and the NVA had suffered heavy casualties.

2) The RVNAF proved its ability, reliability, and competence in fighting the enemy. Communist troops were either held in place, crushed to pieces, or pushed back. Overall, more than 60,000 NVA troops had been killed, several thousand others surrendered or rallied to our side. The morale of communist units were at all time low and VC forces were almost completely annihilated.

3) Perhaps this disastrous disruption of the NVA and VC in the South was not reported to Westmoreland in detail causing him to ask Washington for an additional 200,000 combat troops for Vietnam. On March 10, 1969 the New York Times by disclosing the request sent a shock wave to the nation. On March 19, the House of Representatives passed a resolution calling for an immediate review by Congress of U.S. war policy in Vietnam. On March 22, Johnson announced that Westmoreland was promoted to Army Chief of Staff and would leave Vietnam in June.

Had Westmoreland not asked for additional troops for Vietnam, he would have won the war without discussion or suspicion. And if Johnson, in retaliation for the NVA’s Tet Offensive, had taken decisions to destroy sanctuaries along the borders and stiffen the Rolling Thunder air campaign against Hanoi without target restriction in addition to blockading Hai Phong seaport, the war would have been won. How could the USSR and China intervene for a retaliation to the communists’ attack on the U.S. Embassy in Saigon?

Other facts deserve consideration.

According to Johnson’s newly assigned Secretary of Defense and Chief of the “Tet Inquiry Task Force” Melvin Laird, the Pentagon had no plan to “win the war.” (29) No plan meant that the U.S. had no intention to win the war against North Vietnam by force. Had the U.S. decided to win the war, it could have done in one of the two opportunities I have cited above by using its air power and manpower in an offensive war.

The war was no longer “absolutely winnable” under Nixon administration because three factors had tilted in favor of the NVA: 1) Thời Cơ: time and opportunities; 2) Nhân Hoà: The United States lost its populace support; 3) Địa Lợi: geographical advantage (the NVA had completed the Ho Chi Minh trail and a number of sanctuaries along South Vietnam’s border). In addition, the Nixon administration had opened diplomatic relations with Red China and abandoned South Vietnam by using “Vietnamization” to withdraw its troops and “Peace with Honor” to open peace talks with North Vietnam and to surrender through the January 1973 Paris Accords. President Ford inherited the previous legacy and completed it with the policy “Forget about Vietnam.” The architect of these policies was Henry Kissinger.

One may ask why Nixon and Kissinger had escalated the war in Cambodia, Laos and North Vietnam while pursuing the peace policies. Winston Lord, one of Kissinger’s aides mentioned, “The President (Nixon) felt that he had to demonstrate that he couldn’t be trifled with–and frankly, to demonstrate our toughness to Thiệu.” (30) In fact, the air campaign not only forced Hanoi to come back to the Paris talks, but also threatened President Thiệu to accept the coming peace treaty being negotiated between Kissinger and Thọ. Two other incursions of the ARVN into Cambodian and Laotian territories respectively in April 1970 and January 1971were also Kissinger’s designs, his experiments prior to making a final decision. However, under the brilliant command of their clever, illustrious, and spirited commanders and generals, ARVN units had always shown their fierce, intense and sprightly competence at the battleground. Their ability and effectiveness were also widely highlighted during the Red Summer communist offensive of 1972, when communists again and again exposed their inhumanity and immorality by killing en masse innocent refugees on the “Avenue of Horror” (Highway 1 in Quang Tri) and on route 13 south of An Loc and by randomly shelling cities causing thousands of dead and wounded civilians. Likewise, an immoral politician would ponder how to destroy an impediment that would obstruct his nastily political scheme. The RVNAF was that impediment. The Peace treaty was hastily signed causing this heroic armed forces to fight an imbalanced war without supplies and ammunition like Chang Kei shek’s Nationalist Army did in 1948-1949 in China. That was Kissinger’s scheme.

Had Kissinger not planned to abandon South Vietnam in 1973 during the Vietnamization period, but instead helped the RVNAF to build up at least six more infantry divisions and two more air force divisions and continued military aid, South Vietnam would have survived. However, this was an ILLUSION. The fate of South Vietnam had been sealed on January 21, 1969 when the White House heard echoes of anti-war demonstrators from the Lincoln Memorial.

In conclusion, we have learned many lessons from the 30-year Vietnam War. A last important issue is worthy of note. John Ehrlichman, Nixon’s domestic affairs adviser commented that Nixon had “won a prize in opening China and in forging some kind of alliance with China and Russia–and if the price of that was a cynical peace in Vietnam, then historians are going to have to weigh the morality and pragmatism and all these things that historians like to weigh.”(31)

Though I am not a historian, I thought and agreed with some American historians and strategists that by losing South Vietnam, the United States had closed the Red Chinese Tiger in its den and saved Southeast Asia. Now I know I was WRONG. After several decades of cajoling China, the latter has become a fearsome tiger with two strong wings that would not allow it to stay still. In the last decade, its first wing–a vibrant economy–has established its soft power (quyền lực mềm) in Africa and large parts of the world; and its second wing–its armed force, especially the Navy–has begun to challenge U.S. Navy for the control of South Pacific Ocean and to become a new threat for Indochina, Southeast Asia including Brunei and Borneo. Its hard power will soon come to Vietnam first. In the next decade, the “Yellow Peril” (hoàng hoạ) will become a worldwide threat.

The losses of mainland China in 1949 and South Vietnam in 1975 are the biggest lessons we should learn. The last thing I would like to mention is,

“Ethics in politics brings less misfortune for mankind.”

VAN NGUYEN DUONG

[VAN NGUYEN DUONG’s PAPER at the SACEI’s Conference in Dulles, VA, 9/ 26/ 2009]

NOTES

1. Van Nguyen Duong. The Tragedy of the Vietnam War. Jefferson, NC, McFarland. 2008: v.

2. Ưng Trình. Ngoại Giao Sử. Tân Văn Magazine #23. CA, Little Saigon Pub, May 2009 p. 23.

3. Hoàng Xuân Hản. Một vài kỷ niệm về Hội Nghị Dalat 1946. Tân Văn Magazine #10. CA, Little Saigon Pub, May 2008, pp. 20-25.

4. The Pentagon Papers: Senator Gravel Edition. Boston, MA, Beacon Press. Vol 1, pp 18-19.

5. Hoàng Xuân Hản ,Tân văn Magazine # 10, p. 43.

“La France nouvelle ne cherche pas à domineer l’Indochine. Mais elle entend y demeurer présente. Elle ne considère pas son oeuvre comme terminée. Elle refuse d’abdiquer sa mission culturelle. Elle estime qu’elle seule est en mesure d’assurer l’impulsion et la cơordination de la technique et de l’économie, de la diplomatie et de la defense.

Enfin elle sauvegardera les intérêts moraux et materiels des nationaux.

Tout ceci, dans le plein respect de la personalité nationale et avec la participation active et amicale des peoples Indochinois.”

Dalat le 5 Avril 1946

6. Qiang Zhai. China and the Vietnam War, 1950-1975. Chapel Hill, NC, University of NC Press. 2000: pp. 10-42.

7. The Pentagon Papers, pp. 53-75.

8. Qiang Zhai (2000), p. 44.

9. Hoàng Ngọc Nguyên. Trần Văn Tuyên: Đời Người và Vận Nước. Tân Văn Magazine #4, Nov 2009, p. 66.

10. The Pentagon Papers, pp. 53-75.

11. Ibid

12. Van Nguyen Duong (2008) p. 36.

13. ibid p. 37.

14. Maclear M. The Ten-thousand Day War. New York, NY, St Martin Press. 1981: 59.

15. Dypuy RE, Dupuy TN. The Harper Encyclopedia of Military History. New York, NY, Harper Collins. 1993: p. 1424.

16. Ibid

17. Ibid p. 1425.

18. Ibid

19. Van Nguyen Duong, p.23

20. Nguyễn Kiên Giang. Les grandes Dates du Parti de la Classe Ouvriere du Vietnam. Hanoi, Vietnam, Foreign Languages Publishing House. pp 46-53.

21. Hoàng Văn Chí. From Colonialism to Communism. New Delhi, India, Allied Pub. 1964: p. 13.

22. Van Nguyen Duong p 41.

23. Ibid p. 44

24. Ibid p. 59

25. Ibid

26. Ibid p. 67.

27. Maclear p. 75.

28. Van Nguyen Duong p 127-128

29. Ibid p. 123.

30. Ibid p. 171.

31. Maclear, M. p. 311.

One Comment

Nguyen Ngoc Bich

A good and solid piece, Anh Duong!

Thank you.

Nguyen Ngoc Bich