Dr. Khoi Nguyen’s speech

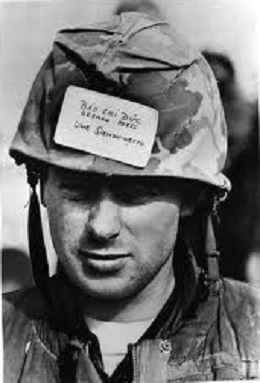

at the May 4, 2013 book signing of Đức

Ladies and Gentlemen,

Dear Uwe and Gillian,

Dear brothers in arms,

Growing up in a war-torn country, one is anxious to discover the root causes of a protracted war in this nation: Why did we have to fight the Communists? Why couldn’t we overcome them in spite of the material aid from western superpowers such as France and the United States? These questions became a constant obsession to me.

Very early in my youth, I pored over literature about the French Indochina war. I got acquainted with names like Jean Lartéguy and Jules Roy describing the tragic destruction of the French Expeditionary forces on Route Coloniale 4 in 1950 when they tried to withdraw from frontier towns of Cao Bang, Lang Son, or the bloody siege of Dien Bien Phu in 1954.

At that age, I could not grasp the fact that the highly technological warfare of the West is no match to the strategy of Mao Tse Tung wasting human lives, waging a long war that will eventually wear out the enemy.

Uwe has brilliantly quoted Mao’s statement in his book: “ He who cannot win the insurrectional war, loses. He who does not lose a protracted insurrectional war, wins”. This seems to be a lesson the West — and we — never learn.

You notice that I mention Mao, not Ho Chi Minh or Vo Nguyen Giap, because right in the beginning, the enemy’s strategy is Mao’s. At the RC4 battles, Chinese military and political advisors such as Cheng Geng and Luo Gui Bo were already present alongside Ho Chi Minh and Vo Nguyen Giap.

Later on, after Dien Bien Phu, our country was divided along the 17th parallel into North and South Viet Nam. Then came the Americans. This time I had all the reasons to rejoice.

“John Wayne is coming to our rescue. How can we lose?” I thought.

Well, several years later, I happened upon a book written by the genius Bernard Fall. At that time this volume was titled, La Guerre d’Indochine 1945-1954. I still keep a copy of it. Only much later, it was translated into English and became renowned under the title, The Street Without Joy. Thereafter, I read other books by Fall, for example The Two Vietnams, Hell in a Small Place, and Last Reflections on a War, the last one written shortly before his death on Highway 1 between Quang Tri and Hue.

Somehow, reading Fall always made me uncomfortable: the truth is that when he noticed the massive involvement of the U.S. conventional armed forces and the way the AFRVN were trained for conventional warfare rather than a long tedious counter-insurrectional warfare, Fall already predicted the downfall of the country. And that make me so uncomfortable for years, until the end.

Not very long after the U.S. involvement began, came Woodstock and the Hippies. With them came leftist anti-war newsmen, for example Neil Sheehan, David Halberstam, Stanley Karnow.

Neil Sheehan wrote The Shining Lie, Halberstam The Best and the Brightest and Stanley Karnow: Viet Nam, a History.

In these books that became much acclaimed, they threw truth and objectivity out of the window.

None of them cared about the Vietnamese soldiers, except in derogatory terms.

None of them cared about the massacre of Hue during the Tet Offensive in 1968.

In his 1,500-page tome, Neil Sheehan glorified John Paul Vann, the American military advisor who never hesitated sacrificing the lives of South Vietnamese soldiers for his own glory.

Later we discovered that Neil Sheehan and David Halberstam had relied on information from Phạm Xuân Ẩn, a top North Vietnamese agent.

And when Stanley Karnow directed the TV series totled, Vietnam, a history, guess whom he used as Vietnamese advisor? Ngô Vĩnh Long, a notorious Communist sympathizer living in Boston.

Only recently, we have begun seeing some of the books written by the former U.S. military advisors to the South Vietnamese army. They praised the South Vietnamese soldiers, which is already a significant improvement on what we had read before. Yet none of these authors mentioned the sufferings of Vietnamese civilians.

Given this state of affairs, Uwe Siemon-Netto’s book, Đức, comes along today as a catharsis at long last, a soothing wound-healing process for all of us, because we find he does actually focus on us; we matter to him.

I just finished this volume a week ago. You will be disappointed if you try to look for statistics of the bloody war. You don’t even find a map. You will be disappointed if are looking for a rationale for the war in this volume or a political statement.

Đức just relates raw experiences, the personal experiences of a decent journalist connecting with the people. It takes a man who grew up in the aftermath of World War II, among the ruins of a devastated Germany, to feel compassion for the misery of the Vietnamese people.

I will not say that you will “enjoy” the book because it will give you pains, flashbacks. It will force you to face the violence and the absolute efficiency of the enemy’s brutality and ruthlessness. Only then, after shedding tears for the utmost sacrifices of the war victims, only then comes finally awakening and redemption.

You will cry and laugh when you read Uwe’s book.

Unlike most of us who were assigned to a battalion or a field hospital, witnessing the war only in a restricted area of a military corps or a city or town, a journalist like Uwe has a bird’s eye view.

One day he might be in the middle of a battle, and on the following afternoon he might attend the so-called five o’clock follies, the daily press conference of the US military. There he experiences a media Theater of the Absurd, where nothing made sense. He is given meaningless statistics: numbers wedded to acronyms such as of KIA, WIA and MIA (killed, wounded and missing in action).

One day, Uwe is with a platoon, patrolling a sector controlled by the enemy, the next day he would be in an airplane interviewing Prime Minister Nguyen Cao Ky.

You will cry with him when he recounts the execution of the whole family of a South Vietnamese village chief, all hanged, the chief with his genitals cut off and stuffed into his mouth.

You will cry and smile with him at the same time when he talks about the urchins of Saigon, kids who lived on the streets of Saigon, the ones we used to call Trẻ Bụi Đời or “Children of life dust”.

You will cry with him at the mass grave of the victims in Hue during the Tet offensive.

Against my will, I shed tears when I stumbled on an observation of his, which is so identical of mine, yet we never met each other until today. Some how we came to the same conclusion on one unique fact: that a young soldier, when he is dying, first cries out to his MOM. Strange coincidence! Not his sweetheart, but his MOM. I can still vividly remember all these young guys who gave their last breath, calling out to their mothers before I could admit them to the operating room.

Then I burst out of laughing when Uwe quoted Graham Greene, the author of the novel, The Quiet American.

“To take a Annamite to bed with you is like taking a bird,” Green wrote, “They sing and twitter on your pillow.“

I wish that Graham Greene could have a second life right now. Nowadays, a Vietnamese lady would go to bed with you with a huge and loud karaoke machine deafening you with her song.

But I am not going to describe everything Uwe wrote in his book. I strongly recommend you to buy the book both in English and its translation into Vietnamese so brilliantly done by Ly Van Quy and Nguyen Hien. You should not buy one book. You should get at least 10 like me so you can send to your friends.

There is something else the author doesn’t mention in the book: in spite of all the pain and suffering he witnessed, he kept his Christian faith; indeed it became stronger. After the war, he gave pastoral care to American GIs suffering from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. And he earned a Ph.D. in theology, which I find outstanding.

I myself must admit I had my faith shaken.

Recently I read a book from Phan Nhật Nam, ex airborne and renowned South Vietnamese war reporter whom I respect and admire. I have to quote him since he seems to echo innermost feelings after the war, even though I did not have to go through the Calvary Phan Nhật Nam endured: more than 10 years in a North Vietnamese Communist concentration camp for the POWs.

Let me try to translate what Phan Nhật Nam wrote in one of his most recent book: “God is omnipresent and omnipotent, but sometimes I feel that he seems to be indifferent if not to say unfair.

God exists, but so does the devil, who is not God’s equal, but sometimes seems at lest as powerful”.

So Uwe, let me express my gratitude to you for having written this book. The Vietnamese people will appreciate you and love you, in the words of one of the characters in your book, comme la mer, comme le ciel.

May I have one more minute to honor the most admirable person who is with us today: Gillian Siemon-Netto, Gillian can you stand up so we can honor you?

On behalf of everybody here I thank you for the boundless love you give to Uwe, your unfathomable dedication and trust in him and your so generous understanding during his difficult time.

For you gave Uwe a lot of space so that he could experience, mature and harvest the wisdom during his journey through hell. Only then he was he able to write such a powerful book.

So, my friends, take out your checkbooks and buy Uwe’s chef d’oeuvre. I can guarantee it will be on your nightstand for a while as it has been on mine.

Nguyễn Ngọc Khôi, MD

Dr. Khoi Nguyen’s speech

at the May 4, 2013 book signing of Đức

Click & Watch Video

Đức: A reporter’s love for the wounded people of Vietnam

By Uwe Siemon-Netto

Đức is the Vietnamese word for German, and Đức was Uwe Siemon-Netto’s nickname during his time as a Vietnam War correspondent. Exactly four decades after America’s withdrawal from that conflict, Siemon-Netto has chosen Đức as the title for his book about his five years of covering the war for Germany’slargest publishing house.

In the words of Peter R. Kann, the former publisher of the Wall Street Journal, “Uwe Siemon-Netto, the distinguished German journalist, has written a masterful memoir… He captures, as very few others have, the pathos and absurdities, the combat, cruelties and human cost of a conflict, which — as he unflinchingly and correctly argues — the wrong side won.

“From the street cafes of Saigon to special forces outposts in the central highlands, from villages where terror comes at night to the carnage and war crimes visited on the city of Hue at Tet, 1968, Uwe brings a brilliant reportorial talent and touch. Above all, Uwe writes about the Vietnamese people: street urchins and buffalo boys, courageous warriors and hapless war victims, and the full human panoply of a society at war.

“As a German, Uwe had, as he puts it, ‘no dog in this fight’, but he understood the rights and wrongs of this war better than almost anyone and his heart, throughout the powerful and moving volume, is always and ardently with the Vietnamese people.”

Bestseller author Barbara Taylor Bradford called Đức “one of the most touching and moving books I have read in a long time. It is also hilarious… I did cry at times, but I also laughed.” Former UPI editor-in-chief John O’Sullivan, described Đức ” as an “angry account of a betrayal of a nation,” adding, “But there is hope about people on every page too.”

Partly as a result of his Vietnam experiences, Siemon-Netto turned to theology, earning an MA and a Ph.D. in this field and writing a textbook on pastoral care to former warriors, titled,“The Acquittal of God, A Theology for Vietnam Veterans.”

Written in English, Duc will be available on Amazon.com by the end of May. It is also on offer in Vietnamese and a German edition is expected to be ready by early 2014. “This brilliant book reminds me of Theodore White’s In Search of History,” commented Maj. Gen. H.R. McMaster, author of Dereliction of Duty: Lyndon Johnson, Robert McNamara, the Joint Chiefs and the Lies that Led to Vietnam. “Uwe Siemon-Netto challenges facets of our flawed historical memory of the Vietnam War,” McMaster continued.

In his epilogue, Uwe Siemon-Netto raises the timely question of whether contemporary democracies are politically and psychologically equipped and patient enough to fight guerrilla wars to a victorious conclusion. Citing the former North Vietnamese defense minister Vo Nguyen Giap’s assessment that they are not, Siemon-Netto observes in Đức with an eye on Afghanistan, “Even more dangerous totalitarians [than the Vietnamese Communists] are taking note today.”

www.vietthuc.org