In the past month Egypt witnessed a change of leadership within the existing regime, not regime change. Egypt has been, and still is, a military regime with a civilian layer of politicians who administer the day-to-day affairs of the country. The popular revolt that brought down Mubarak has merely stripped the civilian veneer from the main pillar of the regime, the military. But the same people and institutions that repressed and stifled Egyptians for the past 30 years are still in power. The revolution is incomplete

Gene Sharp, a scholar on nonviolent social change, and whose ideas influenced demonstrators in Tunis and Egypt, says that power, even that of the most brutal and oppressive kind, ultimately stems not only from the active support of state institutions but also from the passive support of the people it oppresses. According to Sharp, authoritarian regimes, like Mubarak’s in Egypt, also manage power from the people through the general population’s passive compliance and cooperation with the regime’s expectations. On January 25, 2010, hundreds of thousands of Egyptians finally stopped cooperating with a regime they hated. The result has been revolutionary, but not yet a complete revolution.

The military council that now directly rules Egypt has been unequivocal in its desire to hand the day-to-day administration of state affairs back to a civilian government. With growing labor demands, bottled up frustrations of millions of citizens and high expectations for rapid change it is not surprising that they want to pass this toxic brew back to politicians as fast as possible. In fact, critics say the military is rushing a handover to civilians too quickly, before democratic processes and institutions can take hold. But completing the process of democratization of an authoritarian regime is a process that will take time, as political parties are rehabilitated or formed, election rules are determined and people given a chance to debate the transitional process so that it reflects the needs and desires of a broad range of Egyptian views and opinions.

The question of how this transformation will occur is of the utmost importance. Will this regime continue to exercises power behind a newly woven curtain of civilian rule hastily installed before sound democratic processes and institutions can be established, or actually take the necessary steps to develop a functioning democratic regime. More importantly, will Egyptians return to their habit of passive cooperation with the regime, or are they prepared to force real change for real democratic reform if the military are not up to the task?

The military currently enjoys broad and deep popularity among ordinary Egyptians. This support stems in part due to a popular belief among ordinary Egyptians that the military is, due to conscription, most representative of the population, but also due to their perceived neutrality during recent demonstrations. But now in power, the military will have to show that they are not just concerned with preserving the regime, but in taking the side of democracy activists by pushing through genuine democratic reform.

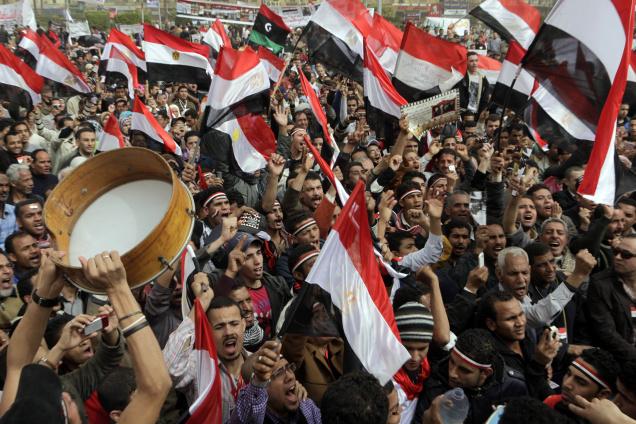

The Independent quotes one Egyptian, Jihad Jibran, in Tahrir saying, “We stood by the army in their revolution,” referring to the 1952 coup that brought down the monarchy and led to the creation of the current regime, adding, “They need to stand with us in ours.” And the military has stood with the people, but more to preserve security, stability and their own perks than out of genuine support for the demonstrators. The army has not intervened in support of a democratic revolution, and must now prove that they really will oversee the development of a process of democratization that ushers in a whole new period in Egypt’s political and social development.

Jibran did not stop at wanting to depose Mubarak. “The goal was never just to get rid of Mubarak. The system is totally corrupt and we won’t go until we see some real reforms… Egypt is too precious to walk away now.” For the popular revolt to become a democratic revolution he should keep a copy of Sharp’s writings close, in case Egyptians have to again cease cooperating with those who now rule Egypt, as the future of of democracy in Egypt always did, and still does, rest in his and his compatriots hands.

Jason Erb