The years 1964-1965 marked a crucial period in the Vietnam War. The Gulf of Tonkin Incident and subsequent U.S. escalation of war against North Vietnam represented a major turning point in the American approach to Indochina, as the Johnson Administration shifted its focus from Saigon to Hanoi as the best way to reverse the deteriorating trend in South Vietnam and to persuade the North Vietnamese leadership to desist from their increasing involvement in the South. How did Beijing react to Washington’s escalation of the conflict in Vietnam? How did Mao Zedong perceive U.S. intentions? Was there a “strategic debate” within the Chinese leadership over the American threat and over strategies that China should adopt in dealing with the United States? What was in Mao’s mind when he decided to commit China’s resources to Hanoi? How and why did a close relationship between Beijing and Hanoi turn sour during the fight against a common foe? Drawing upon recently available Chinese materials, this paper will address these questions.1 The first half of the article is primarily narrative, while the second half provides an analysis of the factors that contributed to China’s decision to commit itself to Hanoi, placing Chinese actions in their domestic and international context.

China’s Role in Vietnam, 1954-1963

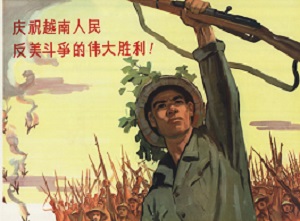

China played an important role in helping Ho Chi Minh win the Anti-French War and in concluding the Geneva Accords in 1954.2 In the decade after the Geneva Conference, Beijing continued to exert influence over developments in Vietnam. At the time of the Geneva Conference, the Vietnamese Communists asked the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to help them consolidate peace in the North, build the army, conduct land reform, rectify the Party, strengthen diplomatic work, administer cities, and restore the economy.3 Accordingly, Beijing sent Fang Yi to head a team of Chinese economic experts to North Vietnam.4 According to the official history of the Chinese Military Advisory Group (CMAG), on 27 June 1955, Vo Nguyen Giap headed a Vietnamese military delegation on a secret visit to Beijing accompanied by Wei Guoqing, head of the CMAG in Vietnam. The Vietnamese visitors held discussions with Chinese Defense Minister Peng Dehuai, and General Petroshevskii, a senior Soviet military advisor in China, regarding the Democratic Republic of Vietnam’s reconstruction of the army and the war plan for the future. The DRV delegation visited the Chinese North Sea Fleet before returning to Hanoi in mid-July. That fall, on 15 October 1955, Vo Nguyen Giap led another secret military delegation to China, where he talked with Peng Dehuai and Soviet General Gushev again about the DRV’s military development and war planning. The Vietnamese inspected Chinese military facilities and academies and watched a Chinese military exercise before traveling back to North Vietnam on December 11.5 The official CMAG history states that during both of Giap’s journeys to Beijing, he “reached agreement” with the Chinese and the Russians “on principal issues.” But it does not explain why Giap had to make a second visit to China shortly after his first tour and why the Soviet participants at the talks changed. Perhaps disagreement emerged during the discussions of Giap’s first trip, leaving some issues unresolved. In fact, according to the study by the researchers at the Guangxi Academy of Social Sciences, the Chinese and the Russians differed over strategies to reunify Vietnam. The Soviet advisors favored peaceful coexistence between North and South Vietnam, urging Hanoi to “reunify the country through peaceful means on the basis of independence and democracy.” The Chinese Communists, conversely, contended that because of imperialist sabotage it was impossible to reunify Vietnam through a general election in accordance with the Geneva Accords, and that consequently North Vietnam should prepare for a protracted struggle.6 On 24 December 1955, the Chinese government decided to withdraw the CMAG from Vietnam; Peng Dehuai notified Vo Nguyen Giap of this decision. By mid-March 1956, the last members of the CMAG had left the DRV. To replace the formal CMAG, Beijing appointed a smaller team of military experts headed by Wang Yanquan to assist the Vietnamese.7 These developments coincided with a major debate within the Vietnamese Communist leadership in 1956 over who should bear responsibility for mistakes committed during a land reform campaign which had been instituted since 1953 in an imitation of the Chinese model. Truong Chinh, General Secretary of the Vietnamese Workers’ Party (VWP), who was in charge of the land reform program, was removed from his position at a Central Committee Plenum held in September. Le Duan, who became General Secretary later in the year, accused Truong Chinh of applying China’s land reform experience in Vietnam without considering the Vietnamese reality.8 The failure of the land-reform program in the DRV dovetailed with a growing realization that the reunification of the whole of Vietnam, as promised by the Geneva Accords, would not materialize, primarily as a result of U.S. support for the anti-Communist South Vietnamese regime of Ngo Dinh Diem, who refused to hold elections in 1956. As hopes for an early reunification dimmed, the DRV had to face its own economic difficulties. The rice supply became a major problem as Hanoi, no longer able to count on incorporating the rice-producing South into its economy, was forced to seek alternative food sources for the North and to prepare the groundwork for a self-supporting economy. In this regard, leaders in Hanoi continued to seek Chinese advice despite the memory of the poorly-implemented land-reform program. There are indications that the Chinese themselves had drawn lessons from the debacle of the Vietnamese land reform and had become more sensitive to Vietnamese realities when offering suggestions. In April 1956, Deputy Premier Chen Yun, an economic specialist within the CCP, paid an unpublicized visit to Hanoi. At the request of Ho Chi Minh, Chen proposed the principle of “agriculture preceding industry and light industry ahead of heavy industry” in developing the Vietnamese economy. The Vietnamese leadership adopted Chen’s advice.9 Given the fact that the CCP was putting a high premium on the development of heavy industry at home during its First Five-Year Plan at this time, Chen’s emphasis on agriculture and light industry was very unusual, and demonstrated that the Chinese were paying more attention to Vietnamese conditions in their assistance to the DRV. Zhou Enlai echoed Chen’s counsel of caution in economic planning during his tour of Hanoi on 18-22 November 1956, when he told Ho Chi Minh to refrain from haste in collectivizing agriculture: “Such changes must come step by step.”10 Donald S. Zagoria argues in his book Vietnam Triangle that between 1957 and 1960, the DRV shifted its loyalties from Beijing to Moscow in order to obtain Soviet assistance for its economic development.11 In reality, the Hanoi leadership continued to consult the CCP closely on such major issues as economic consolidation in the North and the revolutionary struggle in the South. With the completion of its economic recovery in 1958, the VWP began to pay more attention to strengthening the revolutionary movement in the South. It sought Chinese advice. In the summer of 1958, the VWP presented to the CCP for comment two documents entitled “Our View on the Basic Tasks for Vietnam during the New Stage” and “Certain Opinions Concerning the Unification Line and the Revolutionary Line in the South.” After a careful study, the Chinese leadership responded with a written reply, which pointed out that “the most fundamental, the most crucial, and the most urgent task” for the Vietnamese revolution was to carry out socialist revolution and socialist construction in the North. As to the South, the Chinese reply continued, Hanoi’s task should be to promote “a national and democratic revolution.” But since it was impossible to realize such a revolution at the moment, the Chinese concluded, the VWP should “conduct a long-term underground work, accumulate strength, establish contact with the masses, and wait for opportunities.”12Clearly, Beijing did not wish to see the situation in Vietnam escalate into a major confrontation with the United States. Judging by subsequent developments, the VWP did not ignore the Chinese advice, for between 1958 and 1960 Hanoi concentrated on economic construction in the North, implementing the “Three-Year Plan” of a socialist transformation of the economy and society. The policy of returning to revolutionary war adopted by the VWP Central Committee in May 1959 did not outline any specific strategy to follow. The resolution had merely mentioned that a blend of political and military struggle would be required. During the next two years, debates over strategy and tactics continued within the Hanoi leadership.13 Ho Chi Minh continued to consult the Chinese. In May 1960, North Vietnamese and Chinese leaders held discussions in both Hanoi and Beijing over strategies to pursue in South Vietnam. Zhou Enlai and Deng Xiaoping argued that in general political struggle should be combined with armed conflict and that since specific conditions varied between the city and the countryside in South Vietnam, a flexible strategy of struggle should be adopted. In the city, the Chinese advised, political struggle would generally be recommended, but to deliver a final blow on the Diem regime, armed force would be necessary. Since there was an extensive mass base in the countryside, military struggle should be conducted there, but military struggle should include political struggle.14 The Chinese policymakers, preoccupied with recovery from the economic disasters caused by the Great Leap Forward, clearly did not encourage a major commitment of resources from the North in support of a general offensive in the South at this juncture. In September 1960, the VWP convened its Third National Congress, which made no major recommendations affecting existing strategy but simply stated that disintegration was replacing stability in the South. To take advantage of this new situation, the Congress urged the party to carry out both political and military struggle in the South and called for an increase of support from the North.15 This emphasis on a combination of political and military struggle in the South reflected to some degree the Chinese suggestion of caution. In the spring of 1961, U.S President John F. Kennedy approved an increase in the Military Assistance and Advisory Group (MAAG) of 100 advisers and sent to Vietnam 400 Special Forces troops to train the South Vietnamese in counterinsurgency techniques. This escalation of U.S. involvement in Indochina aroused Chinese leaders’ concern. During DRV Premier Pham Van Dong’s visit to Beijing in June 1961, Mao expressed a general support for the waging of an armed struggle by the South Vietnamese people while Zhou Enlai continued to stress flexibility in tactics and the importance of “blending legal and illegal struggle and combining political and military approaches.”16 1962 saw a major turning point in both U.S. involvement in Vietnam and in Chinese attitudes toward the conflict. In February, Washington established in Saigon the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MAC,V), to replace the MAAG. The Kennedy Administration coupled this move with a drastic increase in the number of American “advisers” and the amount of military hardware it was sending to the Diem regime, marking a new level of U.S. intervention in Vietnam. That spring, an important debate broke out within the Chinese leadership over the estimation of a world war, the possibility of peaceful coexistence with capitalist countries, and the degree of China’s support for national liberation movements. On February 27, Wang Jiaxiang, Director of the CCP Foreign Liaison Department, sent a letter to Zhou Enlai, Deng Xiaoping, and Chen Yi (the three PRC officials directly in charge of foreign policy), in which he criticized the tendency to overrate the danger of world war and to underestimate the possibility of peaceful coexistence with imperialism. In terms of support for national liberation movements, Wang emphasized restraint, calling attention to China’s own economic problems and limitations in resources. On the issue of Vietnam, he asked the party to “guard against a Korea-style war created by American imperialists,” and warned of the danger of “Khrushchev and his associates dragging us into the trap of war.” Wang proposed that in order to adjust and restore the economy and win time to tide over difficulties, China should adopt a policy of peace and conciliation in foreign affairs, and that in the area of foreign aid China should not do what it cannot afford.17 But Mao rejected Wang’s proposal, condemning Wang as promoting a “revisionist” foreign policy of “three appeasements and one reduction” (appeasement of imperialism, revisionism, and international reactionaries, and reduction of assistance to national liberation movements).18 The outcome of the debate had major implications for China’s policy toward Vietnam. If Wang’s moderate suggestions had been adopted, it would have meant a limited Chinese role in Indochina. But Mao had switched to a militant line, choosing confrontation with the United States. This turn to the left in foreign policy accorded with Mao’s reemphasis on class struggle and radical politics in Chinese domestic affairs in 1962. It also anticipated an active Chinese role in the unfolding crisis in Vietnam. With the rejection of Wang’s proposal, an opportunity to avert the later Sino-American hostility over Indochina was missed. In the summer of 1962, Ho Chi Minh and Nguyen Chi Thanh came to Beijing to discuss with Chinese leaders the serious situation created by the U.S. intervention in Vietnam and the possibility of an American attack against North Vietnam. Ho asked the Chinese to provide support for the guerrilla movement in South Vietnam. Beijing satisfied Ho’s demand by agreeing to give the DRV free of charge 90,000 rifles and guns that could equip 230 infantry battalions. These weapons would be used to support guerrilla warfare in the South.19 In March 1963, Luo Ruiqing, Chief of Staff of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA), visited the DRV and discussed with his hosts how China might support Hanoi if the United States attacked North Vietnam.20 Two months later, Liu Shaoqi, Chairman of the PRC, traveled to Hanoi, where he told Ho Chi Minh: “We are standing by your side, and if war broke out, you can regard China as your rear.”21 Clearly Beijing was making a major commitment to Hanoi in early 1963. Toward the end of the year, Chinese and North Vietnamese officials discussed Beijing’s assistance in constructing defense works and naval bases in the northeastern part of the DRV.22 According to a Chinese source, in 1963 China and the DRV made an agreement under which Beijing would send combat troops into North Vietnam if American soldiers crossed the Seventeenth Parallel to attack the North. The Chinese soldiers would stay and fight in the North to free the North Vietnamese troops to march to the South.23 But the precise date and details of this agreement remain unclear. In sum, between 1954 and 1963 China was closely involved in the development of Hanoi’s policy. The CCP urged Ho Chi Minh to concentrate on consolidating the DRV and to combine political and military struggles in the South. Although before 1962 Beijing policy makers were not eager to see a rapid intensification of the revolutionary war in South Vietnam, neither did they discourage their comrades in Hanoi from increasing military operations there. Between 1956 and 1963, China provided the DRV with 270,000 guns, over 10,000 pieces of artillery, nearly 200 million bullets, 2.02 million artillery shells, 15,000 wire transmitters, 5,000 radio transmitters, over 1,000 trucks, 15 aircraft, 28 war ships, and 1.18 million sets of uniforms. The total value of China’s assistance to Hanoi during this period amounted to 320 million yuan.24 1962 was a crucial year in the evolution of China’s attitudes toward Vietnam. Abandoning the cautious approach, Mao opted for confrontation with the United States and decided to commit China’s resources to Hanoi. Beijing’s massive supply of weapons to the DRV in 1962 helped Ho Chi Minh to intensify guerrilla warfare in the South, triggering greater U.S. intervention. By the end of 1963, Chinese leaders had become very nervous about American intentions in Vietnam but were ready to provide full support for the DRV in confronting the United States.

China’s Reaction to U.S. Escalation

In the first half of 1964, the attention of U.S. officials was shifting increasingly from South Vietnam toward Hanoi. This trend reflected mounting concern over the infiltration of men and supplies from the North and a growing dissatisfaction with a policy that allowed Hanoi to encourage the insurgency without punishment. In addition to expanding covert operations in North Vietnam, including intelligence overflights, the dropping of propaganda leaflets, and OPLAN 34A commando raids along the North Vietnamese coast, the Johnson Administration also conveyed to Pham Van Dong through a Canadian diplomat on June 17 the message that the United States was ready to exert increasingly heavy military pressure on the DRV to force it to reduce or terminate its encouragement of guerrilla activities in South Vietnam. But the North Vietnamese leader refused to yield to the American pressure, declaring that Hanoi would not stop its support for the struggle of liberation in the South.25 Mao watched these developments closely. Anticipating new trouble, the chairman told General Van Tien Dung, Chief of Staff of the (North) Vietnamese People’s Army, in June: “Our two parties and two countries must cooperate and fight the enemy together. Your business is my business and my business is your business. In other words, our two sides must deal with the enemy together without conditions.”26 Between July 5 and 8, Zhou Enlai led a CCP delegation to Hanoi, where he discussed with leaders from the DRV and Pathet Lao the situations in South Vietnam and Laos.27 Although the details of these talks are unknown, clearly the three Communist parties were stepping up their coordination to confront the increasing threat from the United States. Immediately after the Gulf of Tonkin Incident, Zhou Enlai and Luo Ruiqing sent a cable on August 5 to Ho Chi Minh, Pham Van Dong, and Van Tien Dung, asking them to “investigate the situation, work out countermeasures, and be prepared to fight.”28 In the meantime, Beijing instructed the Kunming and Guangzhou Military Regions and the air force and naval units stationed in south and south-west China to assume a state of combat-readiness. Four air divisions and one anti-aircraft division were dispatched into areas adjoining Vietnam and put on a heightened alert status.29 In August, China also sent approximately 15 MiG-15 and MiG-17 jets to Hanoi, agreed to train North Vietnamese pilots, and started to construct new airfields in areas adjacent to the Vietnamese border which would serve as sanctuary and repair and maintenance facilities for Hanoi’s jet fighters.30 By moving new air force units to the border area and building new airfields there, Beijing intended to deter further U.S. expansion of war in South Vietnam and bombardment against the DRV. Between August and September 1964, the PLA also sent an inspection team to the DRV to investigate the situation in case China later needed to dispatch support troops to Vietnam.31 The first months of 1965 witnessed a significant escalation of the American war in Vietnam. On February 7, 9 and 11, U.S. aircraft struck North Vietnamese military installations just across the 17th Parallel, ostensibly in retaliation for Vietcong attacks on American barracks near Pleiku and in Qui Nhon. On March 1, the Johnson Administration stopped claiming that its air attacks on North Vietnam were reprisals for specific Communist assaults in South Vietnam and began a continuous air bombing campaign against the DRV. On March 8, two battalions of Marines armed with tanks and 8-inch howitzers landed at Danang.32 Worried about the increasing U.S. involvement in Vietnam, Zhou Enlai on April 2 asked Pakistani President Ayub Khan to convey to President Johnson a four-point message: (1) China will not take the initiative to provoke a war with the United States. (2) The Chinese mean what they say. In other words, if any country in Asia, Africa, or elsewhere meets with aggression by the imperialists headed by the United States, the Chinese government and people will definitely give it support and assistance. Should such just action bring on American aggression against China, we will unhesitatingly rise in resistance and fight to the end. (3) China is prepared. Should the United States impose a war on China, it can be said with certainty that, once in China, the United States will not be able to pull out, however many men it may send over and whatever weapons it may use, nuclear weapons included. (4) Once the war breaks out, it will have no boundaries. If the American madmen bombard China without constraints, China will not sit there waiting to die. If they come from the sky, we will fight back on the ground. Bombing means war. The war can not have boundaries. It is impossible for the United States to finish the war simply by relying on a policy of bombing.33 This was the most serious warning issued by the Chinese government to the United States, and given the caution exercised by President Johnson in carrying out the “Rolling Thunder” operations against the DRV, it was one that Washington did not overlook. Clearly, U.S. leaders had drawn a lesson from the Korean War, when the Truman Administration’s failure to heed Beijing warning against crossing the 38th parallel led to a bloody confrontation between the United States and China. The U.S. escalation in early 1965 made the DRV desperate for help. Le Duan and Vo Nguyen Giap rushed to Beijing in early April to ask China to increase its aid and send troops to Vietnam. Le Duan told Chinese leaders that Hanoi needed “volunteer pilots, volunteer soldiers as well as other necessary personnel, including road and bridge engineers.” The Vietnamese envoys expected Chinese volunteer pilots to perform four functions: to limit U.S. bombing to the south of the 20th or 19th parallel, to defend Hanoi, to protect several major transportation lines, and to boost morale.34 On behalf of the Chinese leadership, Liu Shaoqi replied to the Vietnamese visitors on April 8 that “it is the obligation of the Chinese people and party” to support the Vietnamese struggle against the United States. “Our principle is,” Liu continued, “that we will do our best to provide you with whatever you need and whatever we have. If you do not invite us, we will not go to your place. We will send whatever part [of our troops] that you request.You have the complete initiative.”35 In April, China signed several agreements with the DRV concerning the dispatch of Chinese support troops to North Vietnam.36 Between April 21 and 22, Giap discussed with Luo Ruiqing and First Deputy Chief of Staff Yang Chengwu the arrangements for sending Chinese troops.37 In May, Ho Chi Minh paid a secret visit to Mao in Changsha, the chairman’s home province, where he asked Mao to help the DRV repair and build twelve roads in the area north of Hanoi. The Chinese leader accepted Ho’s request and instructed Zhou Enlai to see to the matter.38 In discussions with Luo Ruiqing and Yang Chengwu, Zhou said: “According to Pham Van Dong, U.S. blockade and bombing has reduced supplies to South Vietnam through sea shipment and road transportation. While trying to resume sea transportation, the DRV is also expanding the corridor in Lower Laos and roads in the South. Their troops would go to the South to build roads. Therefore they need our support to construct roads in the North.” Zhou decided that the Chinese military should be responsible for road repair and construction in North Vietnam. Yang suggested that since assistance to the DRV involved many military and government departments, a special leadership group should be created to coordinate the work of various agencies. Approving the proposal, Zhou immediately announced the establishment of the “Central Committee and State Council Aid Vietnam Group” with Yang and Li Tianyou (Deputy Chief of Staff) as Director and Vice Director.39 This episode demonstrates Zhou’s characteristic effectiveness in organization and efficiency in administration. In early June, Van Tien Dung held discussions with Luo Ruiqing in Beijing to flesh out the general Chinese plan to assist Vietnam. According to their agreement, if the war remained in the current conditions, the DRV would fight the war by itself and China would provide various kinds of support as the Vietnamese needed. If the United States used its navy and air force to support a South Vietnamese attack on the North, China would also provide naval and air force support to the DRV. If U.S. ground forces were directly used to attack the North, China would use its land forces as strategic reserves for the DRV and conduct military operations whenever necessary. As to the forms of Sino-Vietnamese air force cooperation, Dung and Luo agreed that China could send volunteer pilots to Vietnam to operate Vietnamese aircraft, station both pilots and aircraft in Vietnam airfields, or fly aircraft from bases in China to join combat in Vietnam and only land on Vietnamese bases temporarily for refueling. The third option was known as the “Andong model” (a reference to the pattern of Chinese air force operations during the Korean War). In terms of the methods of employing PRC ground troops, the two military leaders agreed that the Chinese forces would either help to strengthen the defensive position of the DRV troops to prepare for a North Vietnamese counter offensive or launch an offensive themselves to disrupt the enemy’s deployment and win the strategic initiative.40 But despite Liu Shaoqi’s April promise to Le Duan and Luo Ruiqing’s agreement with Van Tien Dung, China in the end failed to provide pilots to Hanoi. According to the Vietnamese “White Paper” of 1979, the Chinese General Staff on 16 July 1965 notified its Vietnamese counterpart that “the time was not appropriate” to send Chinese pilots to Vietnam.41 The PRC’s limited air force capacity may have caused Beijing to have second thoughts, perhaps reinforcing Beijing’s desire to avoid a direct confrontation with the United States. Whatever the reasons for China’s decision, the failure to satisfy Hanoi’s demand must have greatly disappointed the Vietnamese since the control of the air was so crucial for the DRV’s effort to protect itself from the ferocious U.S. bombing, and undoubtedly contributed to North Vietnam’s decision in 1965 to rely more on the Soviet Union for air defense. Beginning in June 1965, China sent ground-to-air missile, anti-aircraft artillery, railroad, engineering, mine-sweeping, and logistical units into North Vietnam to help Hanoi. The total number of Chinese troops in North Vietnam between June 1965 and March 1973 amounted to over 320,000.42 To facilitate supplies into South Vietnam, China created a secret coastal transportation line to ship goods to several islands off Central Vietnam for transit to the South. A secret harbor on China’s Hainan Island was constructed to serve this transportation route. Beijing also operated a costly transportation line through Cambodia to send weapons, munitions, food, and medical supplies into South Vietnam.43 When the last Chinese troops withdrew from Vietnam in August 1973, 1,100 soldiers had lost their lives and 4,200 had been wounded.44 The new materials from China indicate that Beijing provided extensive support (short of volunteer pilots) for Hanoi during the Vietnam War and risked war with the United States in helping the Vietnamese. As Allen S. Whiting has perceptively observed, the deployment of Chinese troops in Vietnam was not carried out under maximum security against detection by Washington. The Chinese troops wore regular uniforms and did not disguise themselves as civilians. The Chinese presence was intentionally communicated to U.S. intelligence through aerial photography and electronic intercepts. This evidence, along with the large base complex that China built at Yen Bai in northwest Vietnam, provided credible and successful deterrence against an American invasion of North Vietnam.45 The specter of a Chinese intervention in a manner similar to the Korean War was a major factor in shaping President Johnson’s gradual approach to the Vietnam War. Johnson wanted to forestall Chinese intervention by keeping the level of military actions against North Vietnam controlled, exact, and below the threshold that would provoke direct Chinese entry. This China-induced U.S. strategy of gradual escalation was a great help for Hanoi, for it gave the Vietnamese communists time to adjust to U.S. bombing and to develop strategies to frustrate American moves. As John Garver has aptly put it, “By helping to induce Washington to adopt this particular strategy, Beijing contributed substantially to Hanoi’s eventual victory over the United States.”46

Explaining PRC Support for the DRV

Mao’s decision to aid Hanoi was closely linked to his perception of U.S. threats to China’s security, his commitment to national liberation movements, his criticism of Soviet revisionist foreign policy, and his domestic need to transform the Chinese state and society. These four factors were mutually related and reinforcing. Sense of Insecurity: Between 1964 and 1965, Mao worried about the increasing American involvement in Vietnam and perceived the United States as posing a serious threat to China’s security. For him, support for North Vietnam was a way of countering the U.S. strategy of containment of China. The Communist success in South Vietnam would prevent the United States from moving closer to the Chinese southern border. On several occasions in 1964, Mao talked about U.S. threats to China and the need for China to prepare for war. During a Central Committee conference held between May 15 and June 17, the chairman contended that “so long as imperialism exists, the danger of war is there. We are not the chief of staff for imperialism and have no idea when it will launch a war. It is the conventional weapon, not the atomic bomb, that will determine the final victory of the war.”47 At first Mao did not expect that the United States would attack North Vietnam directly.48 The Gulf of Tonkin Incident came as a surprise to him. In the wake of the incident, Mao pointed out on October 22 that China must base its plans on war and make active preparations for an early, large-scale, and nuclear war.49 To deal with what he perceived as U.S. military threats, Mao took several domestic measures in 1964, the most important of which was the launching of the massive Third Front project. This program called for heavy investment in the remote provinces of southwestern and western China and envisioned the creation of a huge self-sustaining industrial base area to serve as a strategic reserve in the event China became involved in war. The project had a strong military orientation and was directly triggered by the U.S. escalation of war in Vietnam.50 On 25 April 1964, the War Department of the PLA General Staff drafted a report for Yang Chengwu on how to prevent an enemy surprise attack on China’s economic construction. The report listed four areas vulnerable to such an attack: (1) China’s industry was over-concentrated. About 60 percent of the civil machinery industry, 50 percent of the chemical industry, and 52 percent of the national defense industry were concentrated in 14 major cities with over one million people. (2) Too many people lived in cities. According to the 1962 census, in addition to 14 cities of above one million, 20 cities had a population between 500,000 and one million. Most of these cities were located in the coastal areas and very vulnerable to air strikes. No effective mechanisms existed at the moment to organize anti-air works, evacuate urban populations, continue production, and eliminate the damages of an air strike, especially a nuclear strike. (3) Principal railroad junctions, bridges, and harbors were situated near big and medium-size cities and could easily be destroyed when the enemy attacked the cities. No measures had been taken to protect these transportation points against an enemy attack. In the early stage of war, they could become paralyzed. (4) All of China’s reservoirs had a limited capacity to release water in an emergency. Among the country’s 232 large reservoirs, 52 were located near major transportation lines and 17 close to important cities. In conclusion, the report made it clear that “the problems mentioned above are directly related to the whole armed forces, to the whole people, and to the process of a national defense war.” It asked the State Council “to organize a special committee to study and adopt, in accordance with the possible conditions of the national economy, practical and effective measures to guard against an enemy surprise attack.”51 Yang Chengwu presented the report to Mao, who returned it to Luo Ruiqing and Yang on August 12 with the following comment: “It is an excellent report. It should be carefully studied and gradually implemented.” Mao urged the newly established State Council Special Committee in charge of the Third Front to begin its work immediately.52 Mao’s approval of the report marked the beginning of the Third Front project to relocate China’s industrial resources to the interior. It is important to note the timing of Mao’s reaction to the report–right after the Gulf of Tonkin Incident. The U.S. expansion of the war to North Vietnam had confirmed Mao’s worst suspicions about American intentions. Deputy Prime Minister Li Fuchun became Director, Deputy Prime Minister Bo Yibo and Luo Ruiqing became Vice Directors of the Special Committee. On August 19, they submitted to Mao a detailed proposal on how to implement the Third Front ideas.53 In the meantime, the CCP Secretariat met to discuss the issue. Mao made two speeches at the meetings on August 17 and 20. He asserted that China should be on guard against an aggressive war launched by imperialism. At present, factories were concentrated around big cities and coastal regions, a situation deleterious to war preparation. Factories should be broken into two parts. One part should be relocated to interior areas as early as possible. Every province should establish its own strategic rear base. Departments of industry and transportation should move, so should schools, science academies, and Beijing University. The three railroad lines between Chengdu and Kunming, Sichuan and Yunnan, and Yunnan and Guizhou should be completed as quickly as possible. If there were a shortage of rails, the chairman insisted, rails on other lines could be dismantled. To implement Mao’s instructions, the meetings decided to concentrate China’s financial, material, and human resources on the construction of the Third Front.54 While emphasizing the “big Third Front” plan on the national level, Mao also ordered provinces to proceed with their “small Third Front” projects. The chairman wanted each province to develop its own light armament industry capable of producing rifles, machine guns, canons, and munitions.55 The Third Five-Year Plan was revised to meet the strategic contingency of war preparation. In the modified plan, a total of three billion yuan was appropriated for small Third Front projects. This was a substantial figure, but less than 5 percent of the amount set aside for the big Third Front in this period.56 In sum, the Third Front was a major strategic action designed to provide an alternative industrial base that would enable China to continue production in the event of an attack on its large urban centers. In addition to his apprehension about a strike on China’s urban and coastal areas, Mao also feared that the enemy might deploy paratroop assault forces deep inside China. In a meeting with He Long, Deputy Chairman of the Central Military Commission, Luo Ruiqing, and Yang Chengwu on 28 April 1965, Mao called their attention to such a danger. He ordered them to prepare for the landing of enemy paratroopers in every interior region. The enemy might use paratroops, Mao contended, “to disrupt our rear areas, and to coordinate with a frontal assault. The number of paratroops may not be many. It may involve one or two divisions in each region, or it may involve a smaller unit. In all interior regions, we should build caves in mountains. If no mountain is around, hills should be created to construct defense works. We should be on guard against enemy paratroops deep inside our country and prevent the enemy from marching unstopped into China.”57 It appears that Mao’s attitudes toward the United States hardened between January and April 1965. In an interview with Edgar Snow on January 9, Mao had expressed confidence that Washington would not expand the war to North Vietnam because Secretary of State Dean Rusk had said so. He told Snow that there would be no war between China and the United States if Washington did not send troops to attack China.58 Two days later, the CCP Central Military Commission issued a “Six-Point Directive on the Struggle against U.S. Ships and Aircraft in the South China Sea,” in which it instructed the military not to attack American airplanes that intruded into Chinese airspace in order to avoid a direct military clash with the United States.59 In April, however, Mao rescinded the “Six Point Directive.” Between April 8 and 9, U.S. aircraft flew into China’s airspace over Hainan Island. On April 9, Yang Chengwu reported the incidents to Mao, suggesting that the order not to attack invading U.S. airplanes be lifted and that the air force command take control of the naval air units stationed on Hainan Island. Approving both of Yang’s requests, Mao said that China “should resolutely strike American aircraft that overfly Hainan Island.”60 It is quite possible that the further U.S. escalation of war in Vietnam in the intervening months caused Mao to abandon his earlier restrictions against engaging U.S. aircraft. It is important to point out that the entire Chinese leadership, not just Mao, took the strategic threat from the United States very seriously during this period. Zhou Enlai told Spiro Koleka, First Deputy Chairman of the Council of Ministers of Albania, on 9 May 1965 in Beijing that China was mobilizing its population for war. Although it seemed that the United States had not made up its mind to expand the war to China, the Chinese premier continued, war had its own law of development, usually in a way contrary to the wishes of people. Therefore China had to be prepared.61 Zhou’s remarks indicated that he was familiar with a common pattern in warfare: accidents and miscalculations rather than deliberate planning often lead to war between reluctant opponents. In an address to a Central Military Commission war planning meeting on 19 May 1965, Liu Shaoqi stated: If our preparations are faster and better, war can be delayed…. If we make excellent preparations, the enemy may even dare not to invade…. We must build the big Third Front and the small Third Front and do a good job on every front, including the atomic bomb, the hydrogen bomb, and long-distance missiles. Under such circumstances, even if the United States has bases in Japan, Taiwan, and the Philippines, its ships are big targets out on the sea and it is easy for us to strike them. We should develop as early as possible new technology to attack aircraft and warships so that we can knock out one enemy ship with a single missile. The enemy’s strength is in its navy, air force, atomic bombs, and missiles, but the strength in navy and air force has its limits. If the enemy sends ground troops to invade China, we are not afraid. Therefore, on the one hand we should be prepared for the enemy to come from all directions, including a joint invasion against China by many countries. On the other, we should realize that the enemy lacks justification in sending troops…. This will decide the difference between a just and an unjust war.62 Zhu De remarked at the same meeting that “so long as we have made good preparations on every front, the enemy may not dare to come. We must defend our offshore islands. With these islands in our hands, the enemy will find it difficult to land. If the enemy should launch an attack, we will lure them inside China and then wipe them out completely.”63 Scholars have argued over Beijing’s reaction to the threat posed by U.S. intervention in Vietnam. Much of this argument focuses on the hypothesis of a “strategic debate” in 1965 between Luo Ruiqing and Lin Biao. Various interpretations of this “debate” exist, but most contend that Luo was more sensitive to American actions in Indochina than either Lin or Mao, and that Luo demanded greater military preparations to deal with the threat, including accepting the Soviet proposal of a “united front.”64 However, there is nothing in the recently available Chinese materials to confirm the existence of the “strategic debate” in 1965.65 The often cited evidence to support the hypothesis of a strategic debate is the two articles supposedly written by Luo Ruiqing and Lin Biao on the occasion of the commemoration of V-J day in September 1965.66 In fact, the same writing group organized by Luo Ruiqing in the General Staff was responsible for the preparation of both articles. The final version of the “People’s War” article also incorporated opinions from the writing team led by Kang Sheng. (Operating in the Diaoyutai National Guest House, Kang’s team was famous for writing the nine polemics against Soviet revisionism). Although the article included some of Lin Biao’s previous statements, Lin himself was not involved in its writing. When Luo Ruiqing asked Lin for his instructions about the composition of the article, the Defense Minister said nothing. Zhou Enlai and other standing Politburo members read the piece before its publication.67 The article was approved by the Chinese leadership as a whole and was merely published in Lin Biao’s name. Luo Ruiqing was purged in December 1965 primarily because of his dispute with Lin Biao over domestic military organization rather than over foreign policy issues.68 Luo did not oppose Mao on Vietnam policy. In fact he carried out loyally every Vietnam-related order issued by the chairman. Mao completely dominated the decision making. The origins of the “People’s War” article point to the danger of relying on public pronouncements to gauge inner-party calculations and cast doubts on the utility of the faction model in explaining Chinese foreign policy making.69 Commitment to National Liberation Movements: The second factor that shaped Mao’s decision to support the DRV was his desire to form a broad international united front against both the United States and the Soviet Union. To Mao, national liberation movements in the Third World were the most important potential allies in the coalition that he wanted to establish. In the early 1960s, the chairman developed the concept of “Two Intermediate Zones.” The first zone referred to developed countries, including capitalist states in Europe, Canada, Japan, Australia, and New Zealand. The second zone referred to underdeveloped nations in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. These two zones existed between the two superpowers. Mao believed that countries in these two zones had contradictions with the United States and the Soviet Union and that China should make friends with them to create an international united front against Washington and Moscow.70 Mao initially developed the idea of the “intermediate zone” during the early years of the Cold War. In a discussion with Anna Louise Strong in 1946, the CCP leader first broached the idea. He claimed that the United States and the Soviet Union were “separated by a vast zone including many capitalist, colonial and semi-colonial countries in Europe, Asia, and Africa,” and that it was difficult for “the U.S. reactionaries to attack the Soviet Union before they could subjugate these countries.”71 In the late 1940s and throughout the greater part of the 1950s, Mao leaned to the side of the Soviet Union to balance against the perceived American threat. But beginning in the late 1950s, with the emergence of Sino-Soviet differences, Mao came to revise his characterization of the international situation. He saw China confronting two opponents: the United States and the Soviet Union. To oppose these two foes and break China’s international isolation, Mao proposed the formation of an international united front. Operating from the principle of making friends with countries in the “Two Intermediate Zones,” Mao promoted such anti-American tendencies as French President De Gaulle’s break with the United States in the first zone and championed national liberation movements in the second zone. For Mao, the Vietnam conflict constituted a part of a broader movement across Asia, Africa, and Latin America, which together represented a challenge to imperialism as a whole. China reached out to anti-colonial guerrillas in Angola and Mozambique, to the “progressive” Sihanouk in Cambodia, to the leftist regime under Sukarno in Indonesia, and to the anti-U.S. Castro in Cuba.72 Toward the former socialist camp dominated by the Soviet Union, Mao encouraged Albania to persuade other East European countries to separate from Moscow.73 During this increasingly radical period of Chinese foreign policy, Mao singled out three anti-imperialist heroes for emulation by Third World liberation movements: Ho Chi Minh, Castro, and Ben Bella, the Algerian nationalist leader. In a speech to a delegation of Chilean journalists on 23 June 1964, Mao remarked: “We oppose war, but we support the anti-imperialist war waged by oppressed peoples. We support the revolutionary war in Cuba and Algeria. We also support the anti-U.S.-imperialist war conducted by the South Vietnamese people.”74In another address to a group of visitors from Asia, Africa, and Oceania on July 9, Mao again mentioned the names of Ho Chi Minh, Castro, and Ben Bella as models of anti-colonial and anti-imperialist struggle.75 Envisioning China as a spokesman for the Third World independence cause, Mao believed that the Chinese revolutionary experience was relevant to the struggle of liberation movements in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. By firmly backing the Vietnamese struggle against the United States, he wanted to demonstrate to Third World countries and movements that China was their true friend. Victory for North Vietnam’s war of national unification with China’s support would show the political correctness of Mao’s more militant strategy for coping with U.S. imperialism and the incorrectness of Khrushchev’s policy of peaceful coexistence. A number of Chinese anti-imperialist initiatives, however, ended in a debacle in 1965. First Ben Bella was overthrown in Algeria in June, leading the Afro-Asian movement to lean in a more pro-Soviet direction due to the influence of Nehru in India and Tito in Yugoslavia. The fall of Ben Bella frustrated Mao’s bid for leadership in the Third World through the holding of a “second Bandung” conference of Afro-Asian leaders. Then in September, Sukarno was toppled in a right-wing counter-coup, derailing Beijing’s plan to promote a militant “united front” between Sukarno and the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI). The Chinese behavior, nevertheless, did convince leaders in Washington that Beijing was a dangerous gambler in international politics and that American intervention in Vietnam was necessary to undermine a Chinese plot of global subversion by proxy.76 Criticism of Soviet Revisionism: Mao’s firm commitment to North Vietnam also needs to be considered in the context of the unfolding Sino-Soviet split. By 1963, Beijing and Moscow had completely broken apart after three years of increasingly abusive polemics. The conclusion of the Soviet-American partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty in July 1963 was a major turning point in Sino-Soviet relations. Thereafter the Beijing leadership publicly denounced any suggestion that China was subject to any degree of Soviet protection and directly criticized Moscow for collaborating with Washington against China. The effect of the Sino-Soviet split on Vietnam soon manifested itself as Beijing and Moscow wooed Hanoi to take sides in their ideological dispute. After the ouster of Khrushchev in October 1964, the new leadership in the Kremlin invited the CCP to send a delegation to the October Revolution celebrations. Beijing dispatched Zhou Enlai and He Long to Moscow for the primary purpose of sounding out Leonid Brezhnev and Alexei Kosygin on the many issues in dispute: Khrushchev’s long-postponed plan to convene an international Communist meeting, support for revolutionary movements, peaceful coexistence with the United States, attitudes toward Tito, and “revisionist” domestic policies within the Soviet Union. The Chinese discovered during their tour on November 5-13 that nothing basic had changed in the Soviet position: the new leaders in Moscow desired an improvement in Sino-Soviet relations on the condition that Beijing stopped its criticisms and limited competition in foreign policy, probably in return for the resumption of Soviet economic aid.77 Instead of finding an opportunity to improve mutual understanding, the Chinese visitors found their stay in Moscow unpleasant and the relationship with the Soviet Union even worse. During a Soviet reception, Marshal Rodion Malinovsky suggested to Zhou Enlai and He Long that just like the Russians had ousted Khrushchev, the Chinese should overthrow Mao. The Chinese indignantly rejected this proposal: Zhou even registered a strong protest with the Soviet leadership, calling Malinovsky’s remarks “a serious political incident.”78 Zhou Enlai told the Cuban Communist delegation during a breakfast meeting in the Chinese Embassy on November 9 that Malinovsky “insulted Comrade Mao Zedong, the Chinese people, the Chinese party, and myself,” and that the current leadership in the Kremlin inherited “Khrushchev’s working and thought style.”79 Before Zhou’s journey to Moscow, the Chinese leadership had suggested to the Vietnamese Communists that they also send people to travel with Zhou to Moscow to see whether there were changes in the new Soviet leaders’ policy. Zhou told Ho Chi Minh and Le Duan later in Hanoi, on 1 March 1965, that he was “disappointed” with what he had seen in Moscow, and that “the new Soviet leaders are following nothing but Khrushchevism.”80 Clearly Zhou wanted the Hanoi leadership to side with the PRC in the continuing Sino-Soviet dispute, and Beijing’s extensive aid to the DRV was designed to draw Hanoi to China’s orbit. The collective leadership which succeeded Khrushchev was more forthcoming in support of the DRV. During his visit to Hanoi on 7-10 February 1965, Kosygin called for a total U.S. withdrawal from South Vietnam and promised Soviet material aid for Ho Chi Minh’s struggle. The fact that a group of missile experts accompanied Kosygin indicated that the Kremlin was providing support in that crucial area. The two sides concluded formal military and economic agreements on February 10.81 Clearly the Soviets were competing with the Chinese to win the allegiance of the Vietnamese Communists. Through its new gestures to Hanoi, Moscow wanted to offset Chinese influence and demonstrate its ideological rectitude on issues of national liberation. The new solidarity with Hanoi, however, complicated Soviet relations with the United States, and after 1965, the Soviet Union found itself at loggerheads with Washington. While Moscow gained greater influence in Hanoi because of the North Vietnamese need for Soviet material assistance against U.S. bombing, it at the same time lost flexibility because of the impossibility of retreat from the commitment to a brother Communist state under attack by imperialism. Before 1964, Hanoi was virtually on China’s side in the bifurcated international communist movement. After the fall of Khrushchev and the appearance of a more interventionist position under Kosygin and Brezhnev, however, Hanoi adopted a more balanced stand. Leaders in Beijing were nervous about the increase of Soviet influence in Vietnam. According to a Vietnamese source, Deng Xiaoping, Secretary General of the CCP, paid a secret visit to Hanoi shortly after the Gulf of Tonkin Incident in an attempt to wean the Vietnamese away from Moscow with the promise of US$1 billion aid per year.82 China’s strategy to discredit the Soviet Union was to emphasize the “plot” of Soviet-American collaboration at the expense of Vietnam. During his visit to Beijing on 11 February 1965, Kosygin asked the Chinese to help the United States to “find a way out of Vietnam.” Chinese leaders warned the Russians not to use the Vietnam issue to bargain with the Americans.83 Immediately after his return to Moscow, Kosygin proposed an international conference on Indochina. The Chinese condemned the Soviet move, asserting that the Russians wanted negotiation rather than continued struggle in Vietnam and were conspiring with the Americans to sell out Vietnam. But as R.B. Smith has observed, the Chinese “may have oversimplified a Soviet strategy which was… more subtle…. Moscow’s diplomatic initiative of mid-February may in fact have been timed to coincide with–rather than to constrain–the Communist offensive in South Vietnam.”84 The Chinese criticism of the Soviet peace initiative must have confirmed the American image of China as a warmonger. The Sino-Soviet rivalry over Vietnam certainly provided leaders in Hanoi an opportunity to obtain maximum support from their two Communist allies, but we should not overstate the case. Sometimes the benefits of the Sino-Soviet split for the DRV could be limited. For example, the Hanoi leadership sought a communist international united front to assist their war effort. They wanted Moscow and Beijing to agree on common support actions, particularly on a single integrated logistical system. They failed to achieve this objective primarily because of China’s objection.85 Domestic Need to Transform the Chinese State and Society: Beginning in the late 1950s, Mao became increasingly apprehensive about the potential development of the Chinese revolution. He feared that his life work had created a political structure that would eventually betray his principles and values and become as exploitative as the one it had replaced. His worry about the future of China’s development was closely related to his diagnosis of the degeneration of the Soviet political system and to his fear about the effects of U.S. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles’ strategy of “peaceful evolution.”86 Mao believed that Dulles’ approach to induce a peaceful evolution within the socialist world was taking effect in the Soviet Union, given Khrushchev’s fascination with peaceful coexistence with the capitalist West. Mao wanted to prevent that from happening in China. The problem of succession preoccupied Mao throughout the first half of the 1960s. His acute awareness of impending death contributed to his sense of urgency. The U.S. escalation of war in Vietnam made him all the more eager to the put his own house in order. He was afraid that if he did not nip in the bud what he perceived to be revisionist tendencies and if he did not choose a proper successor, after his death China would fall into the hands of Soviet-like revisionists, who would “change the color” of China, abandon support for national liberation struggles, and appease U.S. imperialism. Mao was a man who believed in dialectics. Negative things could be turned into positive matters. The American presence in Indochina was a threat to the Chinese revolution. But on the other hand, Mao found that he could turn the U.S. threat into an advantage, namely, he could use it to intensify domestic anti-imperialist feelings and mobilize the population against revisionists. Mao had successfully employed that strategy during the Civil War against Jiang Jieshi [Chiang Kai-shek]. Now he could apply it again to prepare the masses for the Great Cultural Revolution that he was going to launch. Accordingly, in the wake of the Gulf of Tonkin Incident, Mao unleashed a massive “Aid Vietnam and Resist America” campaign across China.87

Sino-Vietnamese Discord

In its heyday the Sino-Vietnamese friendship was described as “comrades plus brothers,” but shortly after the conclusion of the Vietnam War the two communist states went to war with each other in 1979. How did it happen? In fact signs of differences had already emerged in the early days of China’s intervention in the Vietnam conflict. Two major factors complicated Sino-Vietnamese relations. One was the historical pride and cultural sensitivity that the Vietnamese carried with them in dealing with the Chinese. The other was the effect of the Sino-Soviet split. Throughout their history, the Vietnamese have had a love-hate attitude toward their big northern neighbor. On the one hand, they were eager to borrow advanced institutions and technologies from China; on the other hand, they wanted to preserve their independence and cultural heritage. When they were internally weak and facing external aggression, they sought China’s help and intervention. When they were unified and free from foreign threats, they tended to resent China’s influence. A pattern seems to characterize Sino-Vietnamese relations: the Vietnamese would downplay their inherent differences with the Chinese when they needed China’s assistance to balance against a foreign menace; they would pay more attention to problems in the bilateral relations with China when they were strong and no longer facing an external threat. This pattern certainly applies to the Sino-Vietnamese relationship during the 1950s and the first half of the 1960s. The Vietnamese Communists during this period confronted formidable enemies, the French and the Americans, in their quest for national unification. When the Soviet Union was reluctant to help, China was the only source of support that Hanoi could count upon against the West. Thus Ho Chi Minh avidly sought advice and weapons from China. But sentiments of distrust were never far below the surface. Friction emerged between Chinese military advisers and Vietnamese commanders during the war against the French in the early 1950s.88 Vietnamese distrust of the Chinese also manifested itself when Chinese support troops entered Vietnam in the mid 1960s. When Chinese troops went to Vietnam in 1965, they found themselves in an awkward position. On the one hand, the Vietnamese leadership wanted their service in fighting U.S. aircraft and in building and repairing roads, bridges, and rail lines. On the other hand, the Vietnamese authorities tried to minimize their influence by restricting their contact with the local population. When a Chinese medical team offered medical service to save the life of a Vietnamese woman, Vietnamese officials blocked the effort.89 Informed of incidents like this, Mao urged the Chinese troops in Vietnam to “refrain from being too eager” to help the Vietnamese.90 While the Chinese soldiers were in Vietnam, the Vietnamese media reminded the public that in the past China had invaded Vietnam: the journal Historical Studies published articles in 1965 describing Vietnamese resistance against Chinese imperial dynasties.91 The increasing animosity between Beijing and Moscow and their efforts to win Hanoi’s allegiance put the Vietnamese in a dilemma. On the one hand, the change of Soviet attitudes toward Vietnam from reluctant to active assistance in late 1964 and early 1965 made the Vietnamese more unwilling to echo China’s criticisms of revisionism. On the other hand, they still needed China’s assistance and deterrence. Mao’s rejection of the Soviet proposal of a “united action” to support Vietnam alienated leaders in Hanoi. During Kosygin’s visit to Beijing in February 1965, he proposed to Mao and Zhou that Beijing and Moscow end their mutual criticisms and cooperate on the Vietnam issue. But Mao dismissed Kosygin’s suggestion, asserting that China’s argument with the Soviet Union would continue for another 9,000 years.92 During February and March, 1966, a Japanese Communist Party delegation led by Secretary General Miyamoto Kenji, visited China and the DRV, with the purpose of encouraging “joint action” by China and the Soviet Union to support Vietnam. Miyamoto first discussed the idea with a CCP delegation led by Zhou Enlai, Deng Xiaoping, and Peng Zhen in Beijing. The two sides worked out a communiqué that went part of the way toward the “united action” proposal. But when Miyamoto, accompanied by Deng, came to see Mao in Conghua, Guangdong, the chairman burst into a rage, insisting that the communiqué must stress a united front against both the United States and the Soviet Union. Miyamoto disagreed, so the Beijing communiqué was torn up.93 Clearly, Mao by this time had connected the criticism of Soviet revisionism with the domestic struggle against top party leaders headed by Liu, Deng, and Peng. It was no wonder that these officials soon became leading targets for attack when the Cultural Revolution swept across China a few months later. In the meantime the Vietnamese made their different attitude toward Moscow clear by deciding to send a delegation to attend the 23rd Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU), which was to be held between March 29 and April 8 and which the Chinese had already decided to boycott. The Vietnamese were walking a tightrope at this time. On the one hand they relied on the vital support of Soviet weapons; on the other hand, they did not want to damage their ties with China. Thus Le Duan and Nguyen Duy Trinh traveled from Hanoi to Beijing on March 22, on their way to Moscow. Although no sign of differences appeared in public during Duan’s talks with Zhou Enlai, China’s unhappiness about the Vietnamese participation in the 23rd Congress can be imagined.94 In sum, the Beijing-Hanoi relationship included both converging and diverging interests. The two countries shared a common ideological outlook and a common concern over American intervention in Indochina, but leaders in Hanoi wanted to avoid the danger of submitting to a dependent relationship with China. So long as policymakers in Hanoi and Beijing shared the common goal of ending the U.S. presence in the region, such divergent interests could be subordinated to their points of agreement. But the turning point came in 1968, when Sino-Soviet relations took a decisive turn for the worse just as Washington made its first tentative moves toward disengagement from South Vietnam. In the new situation, Beijing’s strategic interests began to differ fundamentally from those of Hanoi. Whereas the Chinese now regarded the United States as a potential counterbalance against the Soviet Union, their Vietnamese comrades continued to see Washington as the most dangerous enemy. After the withdrawal of U.S. troops from Vietnam and the unification of the country, Hanoi’s bilateral disputes with Beijing over Cambodia, a territorial disagreement in the South China Sea, and the treatment of Chinese nationals in Vietnam came to the fore, culminating in a direct clash in 1979.

Was China Bluffing During the War?

The fact that Beijing did not openly acknowledge its sizable presence in North Vietnam raised questions about the justification for Washington’s restraint in U.S. conduct of war, both at the time and in later years. Harry G. Summers, the most prominent of revisionist critics of President Johnson’s Vietnam policy, asserts that the United States drew a wrong lesson from the Korean War: “Instead of seeing that it was possible to fight and win a limited war in Asia regardless of Chinese intervention, we…took counsel of our fears and accepted as an article of faith the proposition that we should never again become involved in a land war in Asia. In so doing we allowed our fears to become a kind of self-imposed deterrent and surrendered the initiative to our enemies.” Summers contends that “whether the Soviets or the Chinese ever intended intervention is a matter of conjecture,” and that the United States allowed itself “to be bluffed by China throughout most of the war.” He cites Mao’s rejection of the Soviet 1965 proposal for a joint action to support Vietnam and Mao’s suspicions of Moscow’s plot to draw China into a war with the United States as evidence for the conclusion that Mao was more fearful of Moscow than Washington and, by implication, he was not serious about China’s threats to intervene to help Hanoi.95 Was China not serious in its threats to go to war with the United States in Indochina? As the preceding discussion has shown, Beijing perceived substantial security and ideological interests in Vietnam. From the security perspective, Mao and his associates were genuinely concerned about the American threat from Vietnam (although they did not realize that their own actions, such as the supply of weapons to Hanoi in 1962, had helped precipitate the U.S. escalation of the war) and adopted significant measures at home to prepare for war. China’s assistance to the DRV, to use John Garver’s words, “was Mao’s way of rolling back U.S. containment in Asia.”96 From the viewpoint of ideology, China’s support for North Vietnam served Mao’s purposes of demonstrating to the Third World that Beijing was a spokesman for national liberation struggles and of competing with Moscow for leadership in the international communist movement. If the actions recommended by Summers had been taken by Washington in Vietnam, there would have been a real danger of a Sino-American war with dire consequences for the world. In retrospect, it appears that Johnson had drawn the correct lesson from the Korean War and had been prudent in his approach to the Vietnam conflict.

New Chinese Documents on the Vietnam War Translated by Qiang Zhai

Document 1: Report by the War Department of the General Staff, 25 April 1964. Deputy Chief of Staff Yang97: According to your instruction, we have made a special investigation on the question of how our country’s economic construction should prepare itself for a surprise attack by the enemy. From the several areas that we have looked at, many problems emerge, and some of them are very serious. (1) The industry is over concentrated. About 60 percent of the civil machinery industry, 50 percent of the chemical industry, and 52 percent of the national defense industry (including 72.7 percent of the aircraft industry, 77.8 percent of the warship industry, 59 percent of the radio industry, and 44 percent of the weapons industry) are concentrated in 14 major cities with over one million population. (2) Too many people live in cities. According to the census conducted at the end of 1962, 14 cities in the country have a population over one million, and 20 cities a population between 500,000 and one million. Most of these cities are located in the coastal areas and are very vulnerable to air strikes. No effective mechanisms exist at the moment to organize anti-air works, evacuate urban population, guarantee the continuation of production, and eliminate the damages of an air strike, especially the fallout of a nuclear strike. (3) Principal railroad junctions, bridges, and harbors are situated near big and medium-size cities and can easily be destroyed when the enemy attacks cities. No measures have been taken to protect these transportation points against an enemy attack. In the early stage of war, they can become paralyzed. (4) All reservoirs have a limited capacity to release water in an emergency. Among the country’s 232 large reservoirs with a water holding capacity between 100 million and 350 billion cubic meter, 52 are located near major transportation lines and 17 close to important cities. There are also many small and medium-size reservoirs located near important political, economic, and military areas and key transportation lines. We believe that the problems mentioned above are important ones directly related to the whole armed forces, to the whole people, and to the process of a national defense war. We propose that the State Council organize a special committee to study and adopt, in accordance with the possible conditions of the national economy, practical and feasible measures to guard against an enemy surprise attack. Please tell us whether our report is appropriate.

The War Department of the General Staff, April 25, 1964.