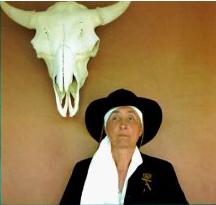

| Georgia O’Keeffe (1887-1986) With a unique, innovative and original style, Georgia O’Keeffe stamped her independent mark on 20th century art and culture. Born into a Wisconsin farming family, which supported and appreciated individuality, Georgia knew her destiny as a teenager. “After we are through school,” she told her classmates, “I am going to give up everything for my art. I am going to live a different kind of life from the rest of you girls.” This collection is from a series of flower paintings in the 20s and 30s. |

She said “The men liked to put me down as the best woman painter. I think I’m one of the best painters” Georgia died in 1986 at the age of 98. She left behind her over 900 paintings, watercolours and drawings. She left a world transformed by technology and war. Most of all, she left a legacy of originality that few have followed. |

|

|||||||||||

When she grew up, women were constrained by American society, in their dress, their education, in their opportunities. Georgia O’Keeffe did not care about these restraints. She dressed in plain, loose clothes, tied her hair back in a braid. She took her own ideas into her art, creating simple paintings with broad areas of smooth, delicate colours. A superb handling of few colours gave her work a lustre and life that matched the organic subjects. She spoke of why she painted flowers; “Nobody sees a flower – really – it is so small – we haven’t time – and to see takes time like to have a friend takes time…So I said to myself – I’ll paint what I see – what the flower is to me, but I’ll paint it big and they will be surprised into taking time to look at it – I will make even busy New Yorkers take time to see what I see of flowers.”

|

|

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|

Tonight I walked into the sunset

Tonight I walked into the sunset

“O’Keeffe’s art refers to determinants, to those things or events that have caused her, provoked her, to create. These necessities obliged her to make art, as she tried to portray sensations, ideas, and situations that for her could be expressed no other way. She wrote to William M. Milliken in 1930, “I see no reason for painting anything that can be put into any other form as well-” To her aesthetic world she was compelled to bring her life and actual experiences, expressed through her direct phenomenological point of view. She leaves us the record of all this in her art. Rarely a strict narrative, her art allows us to remember things she had seen, experienced, or sensed, images grounded in authenticity. She consciously nurtured her memories of events, giving them new life as art.

“A phrase O’Keeffe used in a letter to Anita Pollitzer, “Tonight I walked into the sunset”. (11 September 1916), is like all of her best art: immediate, concrete, all-encompassing, with a surprising syntax. Sunset is the time when the world appears least structured, when forms tend to dissolve and are replaced by new colors and sensations. O’Keeffe acted to suspend time, producing art that would capture the transient. For example, O’Keeffe made of a flower, with all its fragility, a permanent image without season, wilt, or decay. Enlarged and reconstructed in oil on canvas or pastel on paper, it is a vehicle for pure expression rather than an example of botanical illustration. In her art, fleeting effects of natural phenomena or personal emotion become symbols, permanent points of reference.

“O’Keeffe preferred to distance herself from critics, biographers, art historians, or others who probed. Each work represented an intense and above all, personal investment. With her closest friends, however, she was more open. In the letter to Anita Pollitzer, she described an event, but with an extension to the fantastic. O’Keeffe’s imagery is concrete, but the consequence of her concise recounting shocks us to a new awareness. We quickly see her entering the vividly colored sky, becoming one with its greater forces. She does not write of the dust of the trail, the rocks on the road, the length or toil of the walk, but of an effortless, transcendent event. The same happens in her best art – as she suspends the mundane laws of reality and reason. Then she reveals new edges of vision, new attitudes of direct experience, put down in rich color with energetic line in carefully ordered brushstrokes or markings. Each work is self-sufficient, a miniature world with its own rules, bending to her own will. Contrasts of the near and far, both in time and space, distinguish O’Keeffe’s art. She has no aerial perspective, but treats everything in focus, ignoring impressionistic values, the actual envelope of the air, or the limits of human (and even mechanical) vision. O’Keeffe gives us a new world made sharp in all of its large and small parts. The strong ordering, a result of her clear optical and mental vision, can intimidate as well as inspire and challenge.

“Although O’Keeffe has been an influential figure in American art history for the past seven decades, she has also been a target for criticism by outrageous, outraged critics and writers over the years. She had superior internal resolve to withstand Clement Greenberg’s words, “. . . the greatest part of her work adds up to little more than tinted photography. The lapidarian patience she has expended in trimming, breathing upon, and polishing these bits of opaque cellophane betrays a concern that has less to do with art than with private worship and the embellishment of private fetishes with secret and arbitrary meanings” (review, 15 June 1946). She endured a lifetime of sycophants’ and novelists’ fascination with her personal life, her relationships, her status as role model, her every deep or shallow breath.

“Even now the critics are divided in their views on O’Keeffe’s art. Some admire her abstractions, others esteem her figurative works. The former group presents the artist as a progressive. The latter places her within the honored, conservative tradition. The two groups challenge each other for critical control, and there is a struggle within O’Keeffe’s work as well. She herself alternated, blending abstraction and representation, to arrive at a mature, dynamic synthesis, calling it “that memory or dream thing I do that for me comes nearer reality than my objective kind of work” (letter to Dorothy Brett, 15? February 1932). In late February 1924 she wrote to Sherwood Anderson, “My work this year is very much on the ground-There will be only two abstract things-or three at the most-all the rest is objective-as objective as I can make it- . . . I suppose the reason I got down to an effort to be objective is that I didn’t like the interpretations of my other things-” She felt the abstractions allowed too much room for misinterpretation, as the critics wrote their own fixations or autobiographies into hers. She felt “invaded,” unable to accept the point of view that art can also be a resonating membrane for the viewer, who holds the lasting right to its reflections.

“O’Keeffe’s art experienced a distinctly New World freedom, largely in response to the open spaces of rural America. After the claustrophobic beauty of Lake George, she would freely occupy and explore wide-open stretches of the Southwest. This was at a time when the roads of New Mexico were treacherous, if they existed at all, and electricity, telephones, or other utility services were years away. She would test her physical and psychological independence by living beyond the fringe of civilization. This almost biblical exile was her fundamental path to sustained revelation. It was as if she were laying claim to the “faraway” regions, taking hold of their remarkable presences, seeking discoveries for her art. In the Southwest she was free to pursue the fantastic effects of nature, the forces of the elements, and the geological history so dramatically evident in its canyons and stratified hills. She could travel for miles without human contact or traces of development, accepting the risks posed by weather and wild animals. She could also experience the contradictory overlapping of the rituals of the native Americans and those of the colonial Spanish. In this exotic, foreign atmosphere, the artist was, simultaneously, daredevil, participant, and voyeur.

“Her art is memorable. A clear, indelible core image of each work is retained in our mind’s eye after even the briefest glimpse. This is not to say, however, that we remember the profusion of her nuanced details or artful manipulations. O’Keeffe often obscured the hard work and intense thinking that preceded the finished object. These were subordinated to the direct hard punch of the form, the astonishing key of her color, and the unprecedented juxtapositions. It is not enough to quote Alon Bement or Arthur Dow whose teachings and writings influenced the young artist and who held that the highest goal of art was to fill space in a beautiful way. Neither can one credit everything to the emergence of modern photographic vision, despite the notable contributions of Imogen Cunningham, Edward Steichen, Paul Strand, or the turn-of-the-century German Karl Blossfeldt. Despite O’Keeffe’s deep pleasure in Chinese and Japanese art and, indeed, much of the history of art, one still lacks an explanation why her work remains so memorable. Perhaps it is because it is ecstatic, as ecstatic as her relationship to the very real, very visible world around her. To this she adds a distinctive, urgent, and disciplined personal vision. This inner eye of the artist controlled, tightened, made taut the best of her works. O’Keeffe was mad for work. She was adventurous and she had the egotistic notion that she could, in fact, capture an unknown and make it known. Whether O’Keeffe’s work was the result of naive folly or inspired genius, her art bears dramatic witness to her wonder in life and the world.

“In its visual scale relative to literal size, O’Keeffe’s art deceives us. She brilliantly monumentalized her subjects, whether she treated them in a 48 X 40-inch or a 5 X 7-inch canvas. Her small works, though, are among her best and most striking ones. … In each we find emphatic color, composition, clear conception, and visible signs of execution-the trace of her brush, the delicate ridges of pigment. These elements are then put down without compromise or contrivance.

“Her art also speaks about color and its effects. Even the early black-and-white charcoals have a full range, from the highlit whites to the velvety blacks. We supply our own polychromy as we plunge into these charcoals, alluding to her self-described mental visions. The forms are like flickering flames or jewels held aloft by waterspouts. They become animated by our imagination, stimulated by O’Keeffe’s curious effects. The academic tradition of monochrome drawing before the use of color is followed, but a quick shift to expressive color comes in the early 1917 paintings, the so-called “Specials.” These works are abstract swirls, fantasy renderings, strong forces with multiple associations to states of being, dream influences, and the birth of abstraction in early twentieth-century art. O’Keeffe used her color both to seduce and repel. There are paintings, pastels, and watercolors of overwhelming beauty, where delicate hues delight our eye and a luxurious feeling permeates. But in an equal number of works she created harsh collisions of saturated colors whose initial garish appearances deny our appreciation. These recall the spirit of her words to Waldo Frank, “I would like the next [exhibition] to be so magnificently vulgar that all the people who have liked what I have been doing would stop speaking to me – My feeling today is that if I could do that I would be a great success to myself” (letter 10 January 1927).

“O’Keeffe admitted carrying shapes around in her mind for a very long time until she could find the proper colors for them. When found, those colors would release an image from her mental catalogue and allow it to become a painting. O’Keeffe used color as emotion. Through color she would transfer the power and effects of music to canvas. In her abstractions, O’Keeffe wrapped color around the ethereal. Whether her images are abstract or figurative, O’Keeffe gives the viewer a profound lesson in emotional and intellectual coloring. No reproduction will ever do justice to the intensity, the solidity, or the high pitch of these colors, for the notion of local or topical color in her work is only relative, just the beginning point. Indeed, as we return to reality after looking at O’Keeffe’s depictions of landscapes, sunsets, rocks, shells, flowers, any of these natural determinants, we are disappointed. We have come to appreciate and think about those things around us under the spell of her work, but the truth becomes less impressive, milder.

“The artist was finely attuned to the sounds of the natural world. In her letters she describes the wild, blowing wind, the deep stillness, the animal sounds, the rustling of trees. All these seem to penetrate the senses of the artist and find expression in her work. These formed for O’Keeffe a kind of natural music, made up of the life and rhythms of the earth. She made art that alludes to sounds, with references to the audible world, from the din of Manhattan to the pure songs of the prairie. She accomplished this through the form and dynamics of her composition and the pitch of her colors.

“O’Keeffe’s earliest mature works, after c. 1915, are abstractions, dreams and visions made concrete. She would enter periods of mad, crazy work, periods when she knew she had “something to say and feel[ing] as if the whole side of the wall wouldn’t be big enough to say it on and then sitt[ing] down on the floor and try[ing] to get it on a sheet of charcoal paper” (letter to Anita Pollitzer, 13 December 1915). As she followed a compulsive need to get something down in paint, watercolor, or charcoal, she questioned her art and formulated long, rhetorical letters, devaluing, revaluing, looking for the point of personal balance, wondering whether she was to be master or slave.

“The open-ended, exhausting, but exciting works of her period of artistic sclf-discovery found a point of focus by the early 1920S. Now her observations of landscapes, flowers, or other natural shapes were made inventively ambivalent. They became both abstract and figurative, with elements merged so that colored streaks played across the plains, water rose in a siphon contrail, botanical details suggested human anatomy. O’Keeffe, standing firmly behind her work, found the balance that would inform, fuel speculation, and inspire. The strength of these marriages of forms remains evident in all the best work, regardless of date.

“By 1929 O’Keeffe confirmed that her truest, most consistent visual sources were in the American Southwest. These sources refreshed her physically, mentally, artistically. The sky, the vastness, the sounds, the danger of the plains, Badlands, canyons, rocks, and bleached bones of the desert, struck her as authentic and essential to her life as well as to her art. She wrote to Henry McBride from Taos in 1929, “You know I never feel at home in the East like I do out here-and finally feeling in the right place again-I feel like myself-and I like it- . . . Out the very large window to rich green alfalfa fields-then the sage brush and beyond-a most perfect mountain-it makes me feel like flying-and I don’t care what becomes of art”. In the Southwest she found primal mystery, foreign even to this daughter of Sun Prairie, Wisconsin. And it was from the Southwest that O’Keeffe would so forcefully try to capture the wild, unusual essences in her art as it turned more figurative. In search of the marvelous, she advised Russell Vernon Hunter, “Try to paint your world as though you are the first man looking at it-The wind and the licat-and the cold-The dust-and the vast starlit night … When the spring comes I think I must go back to [the Southwest] I sometimes wish I had never seen it-The pull is so strong-so give my greetings to the sky” (21 October 1933). Her letters mention Taos, Abiquiu, the Chama River, the Pedernal, “Black Place … .. Red Hills … .. Gray Hill,” “Lawrence Tree,” all particular sites, points of personal experience that O’Keeffe wove into her art. She wanted to show her wonder. Indeed, it is her wonder, her razor-sharp vision, and her response to that vision that continue to astonish us.

“No artist has seen and painted like O’Keeffe, whose spiritual communion with her subject was of a special quality, unparallelled, and irreducible. In the 1930s and 1940s, her ceaseless searching out and intelligent use of the materials of the Southwest enlivened the potentials of her art. The best of her works cross over to abstraction (“that dream thing,” as O’Keeffe called it), and then loop back to the figurative, engaging the viewer’s full imagination regardless of one’s regional bias. In the 1950s and 1960s O’Keeffe’s sources would become her immediate world of the Abiquiu patio door, the Ghost Ranch post ends, the courtyard flagstones, and her airplane flights above the clouds. She increased her scale to make a number of six-foot-wide paintings and the striking twenty-four-foot wide mural Sky Above Clouds IV. The artist was responding to the younger generation of post-World War 11 artists as they, too, expanded their works to an environmental proportion. Through the late 1960s and 1970s O’Keeffe’s large sky and river paintings, and smaller still-life images of rocks or other natural forms, plus her colorful and broadly brushed watercolors, document her still-vital creative energy.

“Throughout her life, O’Keeffe was as demanding of herself as she was of others. She forcefully edited her oeuvre, critically “grading” the paintings and works on paper. Her highest mark was a star with her initials in the center written on the backboard of the painting. Less favored works were accorded just initials or her signature. She destroyed new work as well as old if it failed to satisfy. Works on paper must have undergone the same judgment process. It was her right, of course, and such acts were consonant with her wish to be mentioned “first or not at all.” If the art did not stand the test of time then O’Keeffe might have, could have made herself disappear.”

Jack Cowart

One Comment

physician assistant

nice post. thanks.