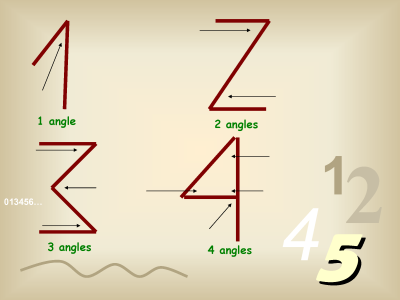

I received an e-mail forward the other day, which contained a PowerPoint presentation giving the supposed origin of Arabic numerals. It claimed that when each number is written with only straight lines, the number of angles created is the same as the quantity being represented. The text accompanying the presentation made the additional claim that these numerals have remained unchanged for thousands of years.

That explanation is completely false. I won’t go into detail on the origins of the numerals in this entry since there are already sources that cover this. There are several Wikipedia articles that overlap on this subject. The first one below is probably best for the history of the symbols. The second one has some good general information. The third one has a good picture of the first known use of Arabic numerals in Europe.

Hindu-Arabic Numeral System

Arabic Numerals

History of the Hindu-Arabic Numeral System

The unique feature of our numbering system, having each position represent a power of 10 (as opposed to a system like Roman numerals), developed some time between the first and sixth centuries. Most of the symbols in that early system came from Brahmi numerals (which themselves came from earlier sources), but a few seem to have come from other sources, such as Buddhist inscriptions. The symbol for zero is an exception, having been invented around the same time as the decimal numbering system. There’s some question to how those Brahmi symbols were developed and what they originally represented, but it certainly wasn’t for counting angles. One, two, and three are pretty easy, since, like Roman Numerals, they were simply one, two, or three lines (even in Arabic numerals, one, two, and three all seem to have been originally related to simple counting – follow those links). The other symbols may have come from their alphabet.

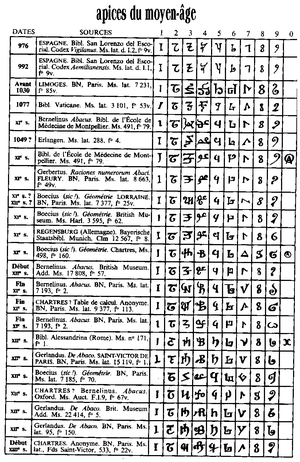

At any rate, the symbols have evolved quite a bit over the centuries, going down different paths in the different regions where they’ve been used. I’ve borrowed one of the images from Wikipedia and posted it below, a table compiled in 1757 showing various usages of numerals in European history (go to Wikipedia for a higher resolution image). Not only would we have a hard time reading the numbers from other regions of the world today, we’d have a hard time reading some of the earliest European uses.

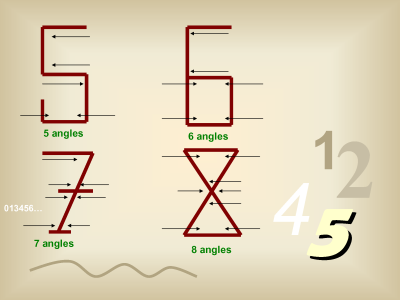

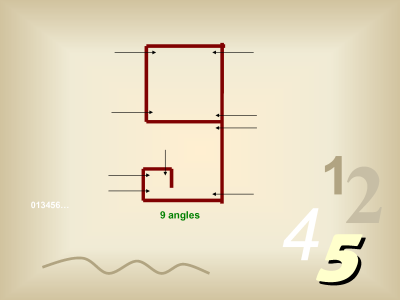

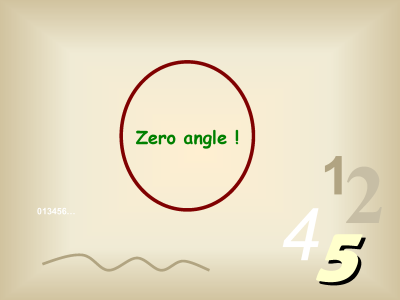

Here’s the full e-mail that I received, with the PowerPoint converted into a series of images. Scroll down for a bit more commentary following this.

How numerals 0 – 9 got their shape – Interesting

Do you know why numbers look like they do? Someone, at some point in time, had to create their shapes and meaning.

Watch this short presentation and then you will know how our Arabic numbers were originally created a very long time ago and what logic the people that created them used to determine their shapes. It is really very simple and quite creative? You have to admire the intelligence of a person that created something so simple and perfect that it has lasted for thousands and thousands of years and will probably never change?

When the presentation gets to the number “seven” you will notice that the 7 has a line through the middle of it. That was the way the Arabic 7 was originally written, and in Europe and certain other areas they still write the 7 that way. Also, in the military, they commonly write it that way. The nine has a kind of curly tail on it that has been reduced, for the most part nowadays, to a simple curve, but the logic involved still applies.

I’ve already given sources showing that this explanation is false, as are the claims in the accompanying text, but let’s have a bit of fun looking at the numbers.

First, look at the 4. That is how 4 is typed, but most people I know don’t write it by hand in that way. Most write it as:

![]()

On the 5, notice the little additional line on the lower left to make the count come out to 5.

Who writes their 7s that way? I know many people put the line through it, but who puts the serifs on the bottom?

The 9 takes the cake, though. It really takes some stretching to imagine that the ‘primitive’ form of 9 would look like that.

If there’s one thing that all our letters and numbers have in common, it’s that they’re relatively simply – just a few strokes to create each one. That’s the way you’d want it for an efficient handwriting system. It’s really tough to imagine that 9 ever having been commonly used.

I suppose that one reason this e-mail continues to make the rounds is summed up in the second sentence of the first paragraph in that e-mail, “Someone, at some point in time, had to create their shapes and meaning.” Many people like to think that something as important as our numerals had to be deliberately invented, that it couldn’t have come about by a haphazard process. But, that’s the way so many things have been developed, especially in language.

Jeff