Overflowing With Color, Energy And Optimism, Kongo’s Graffiti Art Speaks About Living In The Moment

Stepping into Bagnolet, just east of Paris, it’s evident that I’ve left the French capital. Graffiti surrounds me everywhere. No, this isn’t vandalism, but works of art that have been authorized by the forward-thinking city – recognizing the social dimension of the street art movement – which inject dramatic bursts of color into this otherwise dull, drab Parisian suburb. When I enter the studio of Cyril Phan,better known by his street name “Kongo”, I’m greeted by a medium-sized room, where a salvaged metro sign hangs on the wall and dozens of graffiti artworks by different artists who have worked there line the ceiling, and old, worn rugs and drops of paint adorn the floor. Doing laundry and sipping tea as he speaks to me, rock music blaring away in the background, the 46-year-old artist is dressed in a white lab coat over paint-splattered jeans and a heavy-knit cardigan. This atelier, nicknamed “Narvaland”, belongs to Kosmopolite – the name of the association he cofounded – so he shares it with other artists, and comes here to tackle large-format artworks, while his second smaller studio with large, light-filled windows in L’Haÿ-les-Roses in the southern suburbs of Paris, in which two assistants are busily working away, is where smaller pieces are diligently painted in a space he can call his own. The Kosmopolite atelier is a bit like a cultural crossroads to which graffiti artists from around the world come when they need to make a painting – they know they’ll have a place available for them to work.

The French-Vietnamese artist proudly shows me the quality of the materials he works with – many French or Swiss – which guarantee the long-term preservation of his paintings. “For me graffiti, painting a wall that’s repainted the next day doesn’t bother me. That’s the game. On the other hand, when I make paintings, there’s a procedure,” he explains. After a layer of Gesso extra-fine acrylic (base ensuring the paint doesn’t crack) to prepare the linen canvases (linen being a long-lasting material that doesn’t decompose or get moldy), he paints with Lasco or Golden acrylics or MTN spray paint, then finishes the artwork with a colorless Capaplex coating and a satin varnish. He points out the oversized wooden frames to which he fits his paintings, which allow canvases that have moved or slackened over time to be fully stretched out again with a single knock. “In Asia, I couldn’t find linen,” he says. “I like vintage materials, but the métier of weaving this cloth no longer exists. It’s a métier from the north of France that dates back to the 19th century, so this linen is very rare. This French touch is lacking for me in Asia. I had the chance to learn to paint in France and, like it or not, we have a savoir-faire whether it is in frames, canvases, weaving, paints, acrylics – the very basis of painting. In China, ink and porcelain are very good, but I couldn’t find what I was looking for in terms of painting materials, even though everything was much cheaper. In the end, I prefer to return to Paris to produce. I have everything within reach.”

Kongo creates here in France, then goes overseas to exhibit and sell. “People are much more reactive in Asia than here. In France, I stay in my atelier,” he says matter-of-factly. He did, however, previously have a studio-showroom in Hong Kong but shut it after realizing the people there didn’t quite understand graffiti. “Hong Kongers are very much followers at the end of the day. I thought they were the elite of Asia, culturally. And I was wrong. I realized that Singapore and Shanghai had recently overtaken Hong Kong culturally. You can mount projects very quickly in those two cities and, if you excite the market, they bite directly, whereas in Hong Kong, I did three exhibitions and it was all expenses for nothing. I set up projects, met a lot of people, did brunches, lunches, dinners, put on weight, but I couldn’t break through. It was hard.”

Outside the studio, Kongo wants to show me the street frescoes he has done nearby, but they aren’t around anymore, not because the authorities have painted over them but because such is the nature of graffiti, ephemeral artworks in urban spaces – here today, gone tomorrow – and his own philosophy of sharing, exchange and transmission, where established artists make way for younger talents who are given the opportunity to reinvent the walls and buildings of the city.Driving me around, he points out works of numerous styles and subjects, from fantastical wild creatures to cartoon-like American-Indian beauties, by Saile from Chile, Entes from Peru, Milu Correch from Argentina, Pwoz from Guadeloupe, Skio from Paris, Monkeys from Barcelona, Seyb and Alex from Paris, THTF from Lyon, Farm Prod from Brussels, Klash, Maeik, Peter and Markus from Amsterdam and Fenx from Paris. Then he talks about Kosmopolite, which is also the name of an annual street art festival organized by the M.A.C. crew to which he belongs – considered one of the best platforms for launching or promoting young graffiti artists from around the world. This urban color revolution started in Bagnolet – a city that has accompanied the festival since its origins in 2002 – has gone international since 2009 and is now celebrating its 13thanniversary.

Through graffiti, Kongo has been able to leave his mark on any medium – whether wall, canvas, shop window, trunk, bag, scarf or champagne bottle – and revisit it in his own way. He likes the idea of being able to hijack an everyday object and transform it into a work of art, like an old cinder block wall that is there to hide misery and turn it into something that makes life more beautiful. However, graffiti art isn’t something that you can just improvise, picking it up from one day to another. It takes years for a graffiti artist to find his visual identity, elaborate his writing and create the universe that will characterize his entire work. Having begun his career as a self-taught artist almost 30 years ago, Kongo’s style comes from years of experience painting graffiti in the street. The letter, which was a burden for him at school, became his source of inspiration, subject matter and purpose, and now he’s always pushing the limits of letters, words and writing.

His letters come alive and take on a life of their own. These pictorial alphabets reconciling painting and writing are sometimes legible, mysterious or dripping, sometimes round, angular, compressed, stretched, flexible, rigid, rising, falling, moving in all directions or jostling against each other, but always joyful and conveying ideas through their visual power. “Graffiti, it’s words,” he elaborates. “Words are poetry. They are shapes you can reinvent while linking a code. You can reinvent all these letters. I draw portraits through letters. I’m focused on words, letters, explosions, fireworks, flower bouquets, color, joy, optimism. In my way of painting, I want to express life and the desire to live without boundaries. It’s also why I paint on walls, as the canvas restricts me to a format. Painting graffiti on a wall is absolute freedom, especially when you use aerosol sprays, as you can paint on any rough surface.” Although he may have started painting on canvas in 1990, and now exhibits in galleries and sells at auction, he’s not worried about losing street cred, as he still works on the streets and will never stray from his roots.

As a young artist, Kongo’s then-subversive work graced building façades and walls from Paris and New York to Brazil and Hong Kong. Graffiti was not readily accepted and was considered a form of vandalism in the mid-’80s, thus he got into trouble with the police. However, despite years of receiving fines, he has never viewed graffiti painting as vandalism, but as a gift, since he paints on old walls, buys his own materials, gives his own time and beautifies the city through an artwork that the public can admire for free. Over time, graffiti became a form of community street art and the authorities have seen the positive side and started to cooperate with artists to create their art. Kongo made the transition from street to museum in 1991 when he exhibited with his friends at Centre Pompidou in Paris (they were young, naive and confident and didn’t realize the importance of showing at this famous contemporary art museum), which was followed up by many group shows, but it was only 20 years later in 2011 that he held his first solo exhibition at an art gallery.

Kongo’s life and artistic career have been the result of an endless series of encounters and experiences. He’s always lived the life of a nomad, picking up bits and pieces of different cultures as he goes, constantly in mutation, and today spends no more than six months a year in the Paris metropolitan area. Born in Toulouse in 1969 to a Vietnamese father and French mother, the family moved to Vietnam when he was only six months old thanks to his mother’s job as a civil servant. With the fall of Saigon, at the age of six, his father was imprisoned in a re-education camp and his mother smuggled him out of Vietnam under a false identity. He arrived in France three months later with no papers as a refugee of the Vietnam War and took up residence with his grandparents in a working-class neighborhood of Ariège in southern France, where they hadn’t seen an Asian person before. A shy kid who didn’t speak French very well, he was bullied with taunts of “gook” and “filthy Chinese” and constantly got into punch-ups at school – his only outlets for expression were drawing and fighting.

All that changed when his mother was transferred to Brazzaville in Congo, where he was introduced to hip-hop culture and wasn’t considered an immigrant or political refugee. He began to really live there and started having a cultural life. Having lived in Africa from the ages of 13 to 18, his tag “Kongo” is a way of paying tribute to the most cherished part of his childhood. Surrounded by African and mixed-race people who spoke many different languages, children of ambassadors and businessmen, people who travelled a lot, he felt good in his skin and loved the energy. “My experience in Brazzaville where I met people of another social standing allowed me to open my mind and have a different philosophy on life,” he recalls. Then he returned to France in the late 1980s and discovered graffiti art. He landed right smack in the middle of the hip-hop movement, and all his friends were dancers, singers, writers or DJs. Impressed with the graffiti art in Paris, he started expressing himself through graffiti, too – he needed to dream and live his imagination. Graffiti was perfect for him: Cyril was shy, while Kongo painted everywhere. So as one of the early proponents of the nascent French graffiti art scene – having been exported to Paris at the beginning of the 1980s – he began painting around 1987.

“The energy was so strong that I got stuck in it,” Kongo reminisces. “At the time, there was no Internet. A tiny photo from New York was worth more than gold to us. It was the era of magazines and fanzines. A black-and-white photocopy of a piece of graffiti was so meaningful. We weren’t trying to do the same thing, but to understand this energy a bit more. New York had something we didn’t have: they painted on subway trains, which were like mobile galleries that crossed the city 10 times a day, going from point A to point B, from the Bronx to Staten Island. At the time, in the late 1970s, the subway was bankrupt. The trains were dilapidated, so when an artist painted on them, they remained for one or two years like that, crossing the city with his name on it. It was amazing this energy to be able to scream in a creative, not destructive, way.” For him, the art created a real, positive vibe on the streets – it was a symbol of freedom and recognition of the ghetto, where poor people were engaged in healthy competition, driven by those around them to continue improving.

While trying to invent a new way of living, the high school dropout never imagined that this art would bring him all over the world and that the graffiti he painted in the waste grounds of Paris’ suburbs would be known beyond their frontiers, that he would become a respected artist, whose work sells today for around €5,000 per square meter, depending on the medium and rarity of the piece. Kongo and his crew had become famous for painting the largest walls in Paris and, very quickly, they had started to travel, being invited around Europeand to New York, meeting other graffiti artists globally. Every so often now, he visits Guadeloupe, where six of his eight children live. He doesn’t paint there, just spends time with his family, making his way to the volcano and the river every morning. It allows him to reflect, put things into perspective and recharge his batteries, needing this to balance out his life, otherwise he would run out of steam and ideas. He divulges, “This energy is really what compels me and allows me to keep going, and this energy is cultivated. It is ephemeral; the only thing that’s concrete is the end result on canvas, but it doesn’t exist without cultivating this energy.”

Travelling and painting (Kongo creates between 100 and 200 works per year) non-stop, it was in Hong Kong that he met Eric Delannoy, who asked him to customize his son’s baseball cap. Curious, loving to meet people and discuss, he agreed. They sat down, ordered pizza and beer, and the Frenchman wouldn’t stop asking him questions. Kongo thought he was a cop, but he said he was the director of Hermès Hong Kong and Macau. In the end, they exchanged details on coasters and Kongo went back to his friends who were painting in Lan Kwai Fong. He was convinced he had just met a mythomaniac. His friend who lived in Hong Kong retorted, “Cyril, stop talking with people. You speak with everyone. People will tell you anything here – they’re a bunch of talkers and liars. What were you thinking? The guy just wanted to get a cap from you, that’s all.” How wrong he was. Sometimes it pays to be nice to strangers.

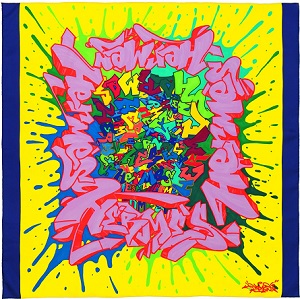

The Graff Hermès silk twill carré designed by Kongo (Photo Dominic Khoo)

The Graff Hermès silk twill carré designed by Kongo (Photo Dominic Khoo)

Kongo was given carte blanche to decorate a Hermès shop window in Hong Kong, then was summoned to a meeting with Pierre-Alexis Dumas, Bali Barret and Christine Duvigneau – the three creative minds of the House who understood graffiti better than some museum curators and immediately recognized the power of the letter and writing – where they asked if he was interested in designing a silk scarf for them.After three years working side by side, the Graff Hermès, a line of irreverent, vibrantly-colored scarves featuring an exclusive all-over signature tag by Kongo, was launched in 2011 and was an immediate sell-out success worldwide. The wearable street art pushed the boundaries of both graffiti and fashion, with Kongo and Hermès sharing a philosophy of quality, manual work, openness and the ability to surprise. For someone who knew nothing about luxury before this experience, Kongo had helped a brand that he thought was for “old ladies” become young again and, at the same time, people became interested in his art following the unlikely collaboration, as it allowed him to win the trust of potential collectors and Hermès gave graffiti the opportunity to be better understood by a wider audience.

Although Kongo’s work may be becoming more mainstream and commercial, when he paints graffiti, he’s not thinking about money, just about expressing himself and getting his name out on the streets. It’s not about politics, social commentary or rebellion either, but art and freedom of expression. He remarks, “Hermès’ logo is a horse-drawn carriage. It’s about the journey. Graffiti is also about travel. Hand-craftsmanship counts for a lot, and it’s spearheaded by the House. Graffiti is also about working by hand: the canvases, you can’t do them except by hand – I don’t use a computer or Photoshop. It’s really an exchange between a human being and an object. Then I’m looking for quality work – that’s why when I started to really work on canvas, I began looking for linen and frames. I began to really identify with the House simply because I saw the savoir-faire, the end result and what luxury really was, and the greatest luxuries are time, savoir-faire and quality.”

Kongo loves collaboration, whether it’s neon lights – a symbol of consumer society found in all the world’s financial and commercial hubs – with contemporary artist Thomas Lélu, a customized trunk-desk with Pinel & Pinel or writing in Aramaic on the body of Jesus sculpted by his artist friend Hacene Sadoune as a way of reappropriating a Christ stolen by religion and give it back to the people. “What interests me in collaboration are projects with substance and encountering other ways of working, meeting people who develop their art in various forms,” he divulges. He has also personalized a Dassault Rafale model airplane that he offered in benefit of the Antoine de Saint-Exupéry Youth Foundation that supports projects for disadvantaged youth worldwide, which went on sale at an Artcurial aeronautical auction in January last year. “Saint-Exupéry or Hermès, they have the same relationship with travel; they have a philosophy. Without a philosophy in life, you’re nothing,” he stresses. Thus his latest project in Bagnolet: “We don’t know where a word or idea can take us, so I want to create a meeting place to transmit to younger artists through graffiti, to show them by my experience or a passion, that you can manage to cross the world and meet fabulous people. Because of life’s mishaps, you may find yourself in difficulty, but that doesn’t mean you’re done for, so for me it is important to be able to convey this energy and philosophy. The common thread will be graffiti because it attracts young people, but the aim is to bring them to classical painting, culture, contemporary painting, to get them to understand the world in which they live a bit more and, the moment they have all these factors, then they can make their choice.”

Kongo is currently holding a solo exhibition, Mr Colorful, at Galerie Matignon in Paris until July 25, 2015.