Các diễn biến tại Trung Đông và Bắc Phi gần đây khiến những người ủng hộ dân chủ và nhân quyền bàn nhiều tới khả năng ‘Cách mạng Hoa Nhài’ sẽ lan tới Việt Nam.

Những bàn tán này càng rôm rả hơn sau khi có những cuộc tụ họp ở một số thành phố tại nước láng giềng Trung Quốc và kinh tế Việt Nam được đánh giá là thuộc hàng 18 nước dễ có nguy cơ vỡ nợ nhất, theo một bài trên Bấm Business Insider hôm 6/3.

Tuy nhiên, ông Carl Robinson một phóng viên kỳ cựu của hãng thông tấn Hoa Kỳ Associate Press, người đưa tin từ Việt Nam trong thời gian chiến tranh, nay sống ở Australia nói có nhiều lý do khiến cách mạng khó xảy ra ở Việt Nam.

Ông Robinson nay quản trị nhóm ‘Các Tay Săn tin thời Cuộc chiến Việt Nam’ dành cho những phóng viên và những người từng làm việc ở miền Nam Việt Nam trước năm 1975 và ông đã đi khắp các vùng miền ở Việt Nam trong 18 tháng qua.

Trong bài “Why Vietnam Won’t Fall”, đăng trên trang World Policy Blog, cựu phóng viên chiến tranh Việt Nam viết:

“Đơn giản là Việt Nam sẽ không sớm đi theo vết xe đổ của Tunisia, Ai Cập và có lẽ là cả Libya.

“Và lý do?

“Thật oái oăm đó cũng chính là những lý do mà Nam Việt Nam trước đây rơi vào tay những người cộng sản cứng rắn và không thỏa hiệp ở miền Bắc hồi năm 1975.

“Không ai muốn chiến đấu. Họ có nhiều thứ khác cần làm hơn.”

Cá nhân chủ nghĩa

Carl Robinson nói sau gần 60 năm cai trị của Đảng Cộng sản ở miền bắc và hơn 35 năm ở miền Nam, cả xã hội Việt Nam ngày nay “cực kỳ cá nhân chủ nghĩa”.

“Thay vì có sự đoàn kết và một mục tiêu chung, mỗi người đều vì chính bản thân, đều có tâm lý mạnh ai người ấy lo vốn dẫn tới sự sụp đổ bất ngờ của miền Nam và sau đó là cuộc bỏ chạy tuyệt vọng của Thuyền Nhân.

“Ví dụ so sánh tốt nhất là một trường đạo nội trú mà trong đó quy định đặt ra để người ta vi phạm hay là để cho người khác tuân theo mà không phải mình.

“Ai cũng bị coi như trẻ con và thường xuyên được dạy giáo lý qua các khẩu hiệu, các nghi lễ và các giấc mộng cao xa.”

Ông Robinson nói nhìn chung người Việt Nam cũng không để ý tới những rao giảng chính trị nhưng họ đủ hài lòng với thu nhập trung bình đang từ từ tăng lên ngưỡng 2000 đô la một năm.

Ông nói: “Dĩ nhiên lạm phát 12% là vấn đề nhưng cách đây ba năm nó lên tới 30%.

“Ai cũng giật gấu vá vai và chịu khó làm việc thêm.

“Chưa ai quên cuộc sống vất vả như thế nào sau năm 1975.”

“… và con cái họ chỉ biết hưởng thụ vật chất và chơi bời.

“Đơn giản là tôi không thể nghĩ ra được những hoàn cảnh mà người Việt Nam sẽ nổi dậy và lật đổ chế độ cộng sản.”

Tham nhũng

Nhưng cựu nhà báo AP cũng nói thực tế không ai ưa chính quyền và người dân đều “đoàn kết” trong chuyện không thích chính phủ.

Người ta nghĩ ra đủ các câu chuyện đùa về đề tài này.

Tham nhũng là vấn đề khác trong xã hội và đây là chủ đề mà các nhà báo được phép đưa tin.

Carl Robinson viết:

“…Trong cuộc sống hàng ngày, mỗi người đều đồng lõa [với tham nhũng] bắt đầu với khoản hối lộ 15 đô la để khỏi bị phạt hay đưa tiền lót tay để nhanh có giấy phép cơi nới nhà.

“Tiền trở lại [xã hội] khi những viên chức tham nhũng, mà lương trung bình chỉ 150 đô la một tháng, tới quán ăn mà tiêu những đồng hối lộ khó kiếm.

“Ai cũng gian giảo theo một cách nào đấy.”

Phản ứng

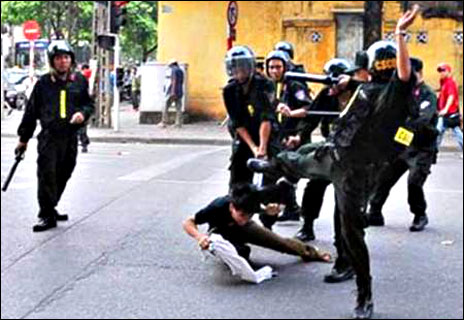

Ông Robinson nói công an Việt nam theo dõi chặt các diễn biến trong xã hội và ra tay một cách “có chọn lựa”, nhất là đối với những cựu đảng viên cộng sản bỏ hàng ngũ và kêu gọi đa nguyên và dân chủ.

Nhưng Việt Nam, ông nói, có ít hơn 100 nhà bất đồng chính kiến bị tù giam hoặc quản thúc tại gia và người ta cũng ít nghe nói tới việc tra tấn người có hệ thống.

Ngoài ra khi người dân tức giận xuống đường, chính quyền cũng có phản ứng và ông Robinson dẫn ra ví dụ về vụ cảnh sát Bấm đánh chết người tại Bắc Giang.

Một khía cạnh nữa mà cựu nhà báo AP đưa ra là những người có khả năng gây ra các vấn đề trong xã hội đã được Việt Nam “xuất khẩu” đi.

Họ đã đi trong giai đoạn Thuyền Nhân và và hàng ngàn cựu quân nhân của miền Nam Việt Nam trước đây đã sang Hoa Kỳ theo thỏa thuận đạt được sau khi quan hệ giữa Hà Nội và Washington bình thường hóa.

Carl Robinson nói ngoại trừ có những bất ngờ lớn, ông tin rằng Việt Nam sẽ tiếp tục thay đổi từ từ và chính quyền cũng quan tâm hơn tới dư luận trong khi Quốc hội bắt đầu thể hiện quyền lực.

Ông Robinson kết luận:

“Sau tất cả những xáo trộn ở Việt Nam trong 60 năm qua, một cuộc cách mạng nữa – hay thậm chí chỉ là nổi loạn – đơn giản là sẽ không xảy ra”.

[Theo BBC]

Why Vietnam Won’t Fall

By Carl Robinson

Long-time Vietnamese dissident Dr. Nguyen Dan Que has no doubt enjoyed his few moments of worldwide attention. Inspired by events in the Middle East, the physician published an Op-Ed piece in The Washington Post last week calling on Hanoi’s diehard Communist regime to become “free and democratic.” Almost immediately, the police arrested and charged him with calling for the overthrow of the government. But just a couple days later, doubtless after a word from Washington, he was released on bail and allowed to return to his home in southern Ho Chi Minh City, the former Saigon.

The 68-year old must be quite chuffed at poking Hanoi’s hornet nest—and seemingly getting away with it. (“Let’s dismantle the Politburo” and “assemble in the streets,” he said recently on the Internet, according to AFP.) He’s been sniping away on human rights and political pluralism since 1978, three years after the collapse of South Vietnam. He’s been arrested four times and spent 20 years in prison. In 1998, Dr Que was amnestied on condition he migrate to the United States. But he refused to leave. Not many Vietnamese would turn down an offer like that.

But just how concerned should Vietnam’s ruling communists be about a contagion from the Middle East suddenly striking their country? After all, their political pre-eminence is guaranteed by the country’s constitution. In early January, Vietnam’s Communist Party Congress re-affirmed that supremacy and vowed never to introduce political pluralism. Hanoi gets lectured on a human rights on a regular basis by Washington and groups like Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International keep a close eye on dissidents with the latter “adopting” several, including Dr Que.

After traveling extensively around Vietnam over the past 18 months, I can report that Hanoi doesn’t have much to worry about. Quite simply, Vietnam isn’t going to follow Tunisia, Egypt and perhaps Libya into collapsing any time soon. And the reason? Why, perversely, for the very same reasons the old South Vietnam fell to the hard-line, no-compromise communists from the North in 1975. Nobody wants to fight. They have better things to do.

After nearly 60 years of Communist Party rule in the North and over 35 years in the South, all of Vietnam today is extremely individualistic. Instead of a common sense of purpose and unity, it’s every person for him- or herself, the sauve qui peux mentality that led to the South’s sudden collapse and later desperate escape of the Boat People. The best analogy is to a church-run boarding school where rules are made to be broken or for others to follow, not me. Everyone is treated like children and receive regular religious teachings in the form of constant slogans, anniversaries and grandiose dreams. When I complained about the dreadful echo of the early morning propaganda loudspeakers to a group of Vietnamese in a coastal town recently, one laughed and said, “That’s just political noise. I don’t hear or see anything!”

Basically, the Vietnamese are satisfied enough with their lot with average incomes steadily rising towards $2000 a year. Sure, 12 precent inflation is a problem, but three years ago it was running close to 30 percent. Everyone makes do, skimping and scrounging, while hustling a bit harder at work. No one has forgotten how tough life was after 1975. Hanoi’s failed socialist economy experiment morphed into today’s free-for-all “market economy” and no one is ready to risk putting where they are today in jeopardy. And their children are totally obsessed with materialism and having fun. I simply cannot imagine any circumstances under which the Vietnamese would rebel and overthrow the communist regime.

Of course, nobody really likes the government. In fact, they are quite united in their dislike, which provides a constant source of conversation—and jokes—over coffee, both a constant of Vietnamese life. Young people easily crack through the firewall around Facebook and post as inanely as their counterparts in the West. With its constant challenges managing a diverse country now over 80 million people, compared to only 30 million at war’s end, the government is a soft target for ridicule as people simply get on with their lives.

Corruption is indeed a serious problem and, within certain bounds, a topic the government-controlled media is allowed to explore. Big scandals erupt with regularity. But in their day-to-day lives, everyone is complicit, starting with $15 bribes to avoid speeding tickets or something under the table to speed up that application for a home extension. The money comes back around when these same corrupt officials, whose average wage is only $150 a month, sit down in a local restaurant to spend their hard-earned bribes. Everyone is on a fiddle of some kind. With so many privately-owned businesses, tax avoidance is rife. Outside the depressing statistics, Vietnam has a huge and thriving secondary economy that runs on US dollars and gold bars.

And so, Vietnam’s dissenters continue to get the headlines. And in the absence of government and business transparency bloggers continue to peddle hearsay. But everything takes place under the watchful eyes and ears of Vietnam’s internal police. Occasionally, they swoop in—but always very selectively, reserving a special ire for former communists who’ve left the tent to call for more pluralism or democracy. The people get the message.

Of course, even one political prisoner is too many. But realistically, Vietnam has fewer than 100 dissidents in jail or house arrest. One rarely hears of systematic torture as in other hard-line regimes. Plus, the regime has been able to export its potential malcontents, first as Boat People and, as the price of normalizing relations with the United States in the 1990’s, visas for the thousands of former South Vietnamese military who spent time in re-education camps after 1975. Another price Washington demanded was freedom of travel, and today, Vietnamese can travel overseas. Some never return, but usually for economic rather than political reasons.

In urging his hard line against the communist regime, Dr Que pointed out in his Post piece that “Hanoi needs Washington much more than Washington needs Hanoi,” especially as tensions rise over Chinese hegemony into the South China Sea and disputes over two island archipelagos. Hanoi complains vehemently when Washington raises human rights issues, particularly in the State Department’s annual reports. But then Vietnam has modified its behaviour, particularly when it comes to religious freedom. Overall, Vietnam is much more open and less restrictive than 15 years ago. Gradual rather than dramatic change is the way things happen in Vietnam.

Barring some monstrous and unforeseen stuff-up, I believe Vietnam will continue down the path of gradual change. The long docile National Assembly has started flexing its muscles in recent years, halting a high-speed North-South rail link on cost grounds and speaking out on a Chinese-run bauxite mining project. The selection of candidates for next year’s election will be interesting to watch. Authorities are also paying closer attention to public opinion, such as cancelling a huge fireworks display last October marking Hanoi’s 1000th birthday after ravishing floods struck central Vietnam. And when people do get angry enough to take to the streets, such as the death of a motorcyclist in police custody in northeast Vietnam last year, the government does respond. After all Vietnam’s upheavals of the past 60 years, another revolution—even rebellion—is simply not in the cards.

Carl Robinson was an Associated Press correspondent in Vietnam during the war. He now runs the Google Group “Vietnam Old Hacks” for former correspondents and others who worked in South Vietnam during the war. Living in Australia since the war, he is also the author of Mongolia: Nomad Empire of Eternal Blue Skies.

Photo Courtesy of Flickr user Noodlepie

Correction (March 11, 10:23 AM): An earlier version of this post misspelled the name of a prominent Vietnamese dissident. His name is Dr. Nguyen Dan Que, not Dr. Nguyen Van Que

3 Comments

Trần Việt

Nói thẳng ra là “thằng dân VN nó hèn lắm”, chỉ mượn cái ngôn ngữ trong lịch sử xa xưa, để tự che đậy cái hèn của mình trong hoàn cảnh “rùa rút cổ” mà thôi ! Cái gì cũng phải trả một giá ! Nói cho cùng, cũng không trách được cái thằng dân mình ở trong nước, tin vào ai được mà “đứng dậy”? Cứ xem hoàn cảnh đáng thương cua Lybia thì thấy ngay, mấy thằng lớn chỉ xui trẻ ăn c… gà, rồi đánh trống bỏ dùi, còn mất thằng chính khách salon chỉ ngồi bàn, câu giờ, lấy cớ này, cớ nọ, còn tính lợi ít lợi nhiều, trong lúc dân Libya vẫn tiếp tục đổ máu hàng nngày !! Miệng thì hô hào dân chủ, cơ hội đến, mà không yểm trợ (như ông tổng Pháp), thì biết bao giờ cho dân chủ được đây ? Chỉ đáng trách và đáng phỉ nhổ vào cái thằng Việt kiều, còn hô hoán, về nước bưng bô cho bạo quyền tiếp tục dầy xéo dân mình. Cái nhục là ở chỗ đó .

Nguyễn Thanh Tùng

Người Việt ở ngoại quốc không sống trong nhà tù lớn ( cả nước Việt hiện nay ) nên không hiểu được tình trạng người dân trong nước . Nên nói điều gì cũng ngon lành cả .

Ngay như TT Dũng công khai tuyên bố vô hiệu vàng và đôla tài sản của dân mà còn không ai dám nói gì kia . Mặc dù nhiều tên cấp dưới của hắn cũng “có quyền nói” đã nói ngược với hắn cũng chẳng được hoặc mất gì ! Hắn vẫn ngang nhiên hủy bỏ tài sản lưu giữ phòng thân của người dân bằng một giọng điệu cả quyết đấy . Có ai dám nói gì đâu ?!

Kim Xuan

Bai nay thuc te va hay qua.

Cam on nguoi viet