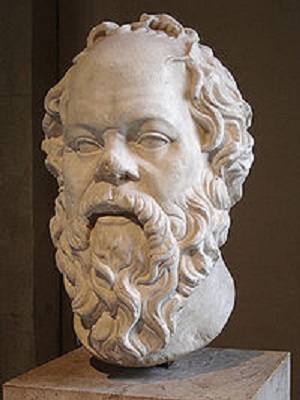

Socrates lived in Athens Greece his entire life (469-399 BC), cajoling his fellow citizens to think hard about questions of truth and justice, convinced as he was that “the unexamined life is not worth living.” While claiming that his wisdom consisted merely in “knowing that he knew nothing,” Socrates did have certain beliefs, chief among them that happiness is obtainable by human effort. Specifically, he recommended gaining rational control over your desires and harmonizing the different parts of your soul. Doing so would produce a divine-like state of inner tranquility that the external would could not effect. True to his word, he cheerfully faced his own death, discussing philosophy right up to the moments before he took the lethal hemlock. Through his influence on Plato and Aristotle, a new era of philosophy was inaugurated and the course of western civilization was decisively shaped.

A LITTLE BACKGROUND

Socrates has a unique place in the history of happiness, as he is the first known figure in the West to argue that happiness is actually obtainable through human effort. He was born in Athens, Greece in 460 BC; like most ancient peoples, the Greeks had a rather pessimistic view of human existence. Happiness was deemed a rare occurrence and reserved only for those whom the gods favored. The idea that one could obtain happiness for oneself was considered hubris, a kind of overreaching pride, and was to be met with harsh punishment.

Against this bleak backdrop the optimistic Socrates enters the picture. The key to happiness, he argues, is to turn attention away from the body and towards the soul. By harmonizing our desires we can learn to pacify the mind and achieve a divine-like state of tranquility. A moral life is to be preferred to an immoral one, primarily because it leads to a happier life. We see right here at the beginning of western philosophy that happiness is at the forefront, linked to other concepts such as virtue, justice, and the ultimate meaning of human existence.

A CASE STUDY OF A HAPPY PERSON

The Roman philosopher Cicero once said that Socrates “wrested philosophy from the heavens and brought it down to earth.” Prior to Socrates, Greek philosophy consisted primarily of metaphysical questions: why does the world stay up? Is the world composed of one substance or many substances? But living amidst the horrors of the Peloponnesian War, Socrates was more interested in ethical and social issues: what is the best way to live? Why be moral when immoral people seem to benefit more? Is happiness satisfying one’s desires or is it virtuous activity?

Famously Socrates was more adept at asking such questions than spoon-feeding us the answers. His “Socratic method” consisted of a process of questioning designed to expose ignorance and clear the way for knowledge. Socrates himself admits that he is ignorant, and yet he became the wisest of all men through this self-knowledge. Like an empty cup Socrates is open to receive the waters of knowledge wherever he may find them; yet through his cross examinations he finds only people who claim to be wise but really know nothing. Most of our cups are too filled with pride, conceit, and beliefs we cling to in order to give us a sense of identity and security. Socrates represents the challenge to all our preconceived opinions, most of which are based on hearsay and faulty logic. Needless to say, many people resented Socrates when he pointed this out to them in the agon or public square.

The price Socrates paid for his honest search for truth was death: he was convicted of “corrupting the youth” and sentenced to die by way of Hemlock poisoning. But here we see the life of Socrates testifies to the truth of his teachings. Instead of bemoaning his fate or blaming the gods, Socrates faces his death with equanimity, even cheerfully discussing philosophy with his friends in the moments before he takes the lethal cup. As someone who trusted in the eternal value of the soul, he was unafraid to meet death, for he believed it was the ultimate release of the soul from the limitations of the body. In contrast to the prevailing Greek belief that death is being condemned to Hades, a place of punishment or wandering aimless ghost-like existence, Socrates looks forward to a place where he can continue his questionings and gain more knowledge. As long as there is a mind that earnestly seeks to explore and understand the world, there will be opportunities to expand one’s consciousness and achieve an increasingly happier mental state.

THREE DIALOGUES ON HAPPINESS: THE EUTHYDEMUS, THE SYMPOSIUM, AND THE REPUBLIC

Although Socrates didn’t write anything himself, his student Plato wrote a voluminous number of dialogues with him as the central character. Scholarly debate still rages as to the relationship between Socrates’ original teachings and Plato’s own evolving ideas. In what follows, we will treat the views expressed by Socrates the character as Socrates’ own views, though it should be noted that the closer we get to a “final answer” or comprehensive theory of happiness, the closer we are to Plato than to the historical Socrates.

The Euthydemus

This is the first piece of philosophy in the West to discuss the concept of happiness, but it is not merely of historical interest. Rather, Socrates presents anargument as to what happiness is that is as powerful today as when he first discussed it over 2400 years ago. Basically, Socrates is concerned to establish two main points: 1) happiness is what all people desire: since it is always the end (goal) of our activities, it is an unconditional good, 2) happiness does not depend on external things, but rather on how those things are used. A wise person will use money in the right way in order to make his life better; an ignorant person will be wasteful and use money poorly, ending up even worse than before. Hence we cannot say that money by itself will make one happy. Money is a conditional good, only good when it is in the hands of a wise person. This same argument can be redeployed for any external good: any possessions, any qualities, even good looks or abilities. A handsome person, for example, can become vain and manipulative and hence misuse his physical gifts. Similarly, an intelligent person can be an even worse criminal than an unintelligent one.

Socrates then presents the following stunning conclusion:

“So what follows from what we’ve said? Isn’t it this, that of the other things none is either good or bad, and that of these two, wisdom is good and ignorance bad?”He agreed.“Well then let’s have a look at what’s left,” I said. “Since all of us desire to be happy, and since we evidently become so on account of our use—that is our good use—of other things, and since knowledge is what provides this goodness of use and also good fortune, every man must, as seems plausible, prepare himself by every means for this: to be as wise as possible. Right?”‘Yes,” he said. (281e2-282a7)

Here Socrates makes it clear that the key to happiness is not to be found in the goods that one accumulates, or even the projects that form the ingredients of one’s life, but rather in the agency of the person himself who gives her life a direction and focus. Also clear from this is a repudiation of the idea that happiness consists merely in the satisfaction of our desires. For in order to determine which desires are worth satisfying, we have to apply our critical and reflective intelligence (this is what Socrates calls “wisdom”). We have to arrive at an understanding of human nature and discover what brings out the best in the human being–which desires are mutually reinforcing, and which prevent us from achieving a sense of overall purpose and well-functioning. No doubt we can also conclude from this that Socrates was the first “positive psychologist,” insofar as he called for a scientific understanding of the human mind in order to find out what truly leads to human happiness.

The Symposium

This dialogue takes place at a dinner party, and the topic of happiness is raised when each of the partygoers takes a turn to deliver a speech in honor of Eros, the god of love and desire. The doctor Eryximachus claims that this god above all others is capable of bringing us happiness, and the playwright Aristophanes agrees, claiming that Eros is “that helper of mankind…who eliminates those evils whose cure brings the greatest happiness to the human race.” (186b) For Eryximachus, Eros is that force which gives life to all things, including human desire, and thus is the source of all goodness. For Aristophanes, Eros is the force which seeks to reunite the human being after its split into male and female opposites.

For Socrates, however, Eros has a darker side, since as the representation of desire, he is constantly longing and never completely satisfied. As such he cannot be a full god, since divinity is supposed to be eternal and self-sufficient. Nevertheless, Eros is vitally important in the human quest for happiness, since he is the intermediary between the human and the divine. Eros is that power of desire which begins by seeking physical pleasures, but can be retrained to pursue the higher things of the mind. The human being can be educated to move away from the love of beautiful things which perish to the pure love of Beauty itself. When this happens, the soul finds complete satisfaction. Socrates describes this as a kind of rapture or epiphany, when the scales falls from one’s eyes and one beholds the truth of one’s existence. As he says:

If…man’s life is ever worth the living, it is when he has attained this vision of the soul of beauty. And once you have seen it, you will never be seduced again by the charm of gold, of dress, of comely boys, you will care nothing for the beauties that used to take your breath away…and when one discerns this beauty one will perceive the true virtue, not virtue’s semblance. And when a man has brought forth and reared this perfect virtue, he shall be called the friend of god, and if ever it is capable of man to enjoy immortality, it shall then be given to him. (212d)

While Socrates and Plato seemed to believe that this mystic rapture was primarily to be achieved by philosophy, there will be others who take up this theme but give it either a religious or aesthetic interpretation: Christian thinkers will pronounce that the greatest happiness is the pure vision of God (Thomas Aquinas), while others will proclaim that it is a vision of beauty in music or art (Schopenhauer). In any case, the idea is that this one overwhelming experience of truth, beauty or the divine, will make all the sufferings and tribulations of our lives meaningful and worth experiencing. It is the Holy Grail that comes only after all our adventures in the wild.

The Republic

In Plato’s masterpiece The Republic, Socrates wants to prove that the just person is happier than the unjust person. Since, as he already argued in theEuthydemus, all men naturally desire happiness, then we should all seek to live a just life. In the process of making this argument, Socrates makes many other points regarding a) what happiness is, b) the relationship between pleasure and happiness, and c) the relationship between pleasure, happiness, and virtue (morality).

The first argument Socrates presents concerns the analogy between health in the body and justice in the soul. We all certainly prefer to be healthy than unhealthy, but health is nothing but the harmony among different parts of the body, each carrying out its proper function. Justice, it turns out, is a similar kind of harmony, but among the different parts of the soul. Injustice on the other hand is defined as a “sort of civil war” between the parts of the soul (444a): a rebellion in which one rogue element—the desirous part of our natures—usurps reason as the controlling power. In contrast, the just soul is one that possesses “psychic harmony:” no matter what life throws at the just man, he never loses his inner composure, and can maintain peace and tranquility despite the harshest of life’s circumstances. Here Socrates effectively redefines the conventional concept of happiness: it is defined in terms of internal benefits and characteristics rather than external ones.

The second argument concerns an analysis of pleasure. Socrates wants to show that living a virtuous life brings greater pleasure than living an unvirtuous life. The point is already connected with the previous one, insofar as one could argue that the psychic harmony that results from a just life brings with it greater peace and inner tranquility, which is more pleasant than the unjust life which tends to bring inner discord, guilt, stress, anxiety, and other characteristics of an unhealthy mind. But Socrates wants to show that there are further considerations to emphasize the higher pleasures of the just life: not merely peace of mind, but the excitement of pursuing knowledge, produces an almost godlike state in the human being. The philosopher is at the pinnacle of this pursuit: having cast off the blinders of ignorance, he can now explore the higher realm of truth, and this experience makes every merely physical pleasure pale in comparison.

Perhaps the most powerful argument, and the one Socrates actually ‘dedicates to Zeus’ (583b-588a) can be called the “relativity of pleasure” argument. Most pleasures are not really pleasures at all, but merely result from the absence of pain. For example, if I am very sick and suddenly get better, I might call my new state pleasurable, but only because it is a relief from my sickness. Soon enough this pleasure will become neutral as I adjust to my new condition. Nearly all of our pleasures are relative like this, hence they are not purely pleasurable. Another example would be the experience of getting high on drugs: this can produce a high state of pleasure in the short-term, but then will inevitably lead to the opposite state of pain. Socrates’ claim is however that there are some pleasures that are not relative, because they concern higher parts of the soul that are not bound to the relativity produced by physical things. These are the philosophical pleasures—the pure pleasure of coming to a greater understanding of reality.

A few hundred years after Socrates, the philosopher Epicurus would take up Socrates’ argument and make a very interesting distinction between “positive” and “negative” pleasures. Positive pleasure depends on pain because it is nothing but the removal of pain: you are thirsty so you drink a glass of water to get some relief. Negative pleasure, however, is that state of harmony where you no longer feel any pain and hence no longer need a positive pleasure to get rid of the pain. Positive pleasure is always quantifiable and falls on a scale: do you have more or less pleasure from sex rather than from eating, for example. Positive pleasures are bound to be frustrating as a result, since there will always be a contrast between the state you are in now and a “higher” state which would make your present experience appear less desirable. Negative pleasures, however, are not quantifiable: you cannot ask “how much are you not feeling hungry?” Epicurus concludes from this that the true state of happiness is the state of negative pleasure, which is basically the state of not experiencing any unfulfilled desires. Needless to say, one can also make connections between this perspective and the Buddhist concept of achieving nirvana through the removal of desire, or the modern writer Eckhart Tolle’s injunction to experience the simple stillness of being without the interference of positive thoughts and emotions.

CONCLUSION

Socrates (as seen through the lens of Plato) can be said to espouse the following ideas about happiness:

- All human beings naturally desire happiness

- Happiness is obtainable and teachable through human effort

- Happiness is directive rather than additive: it depends not on external goods, but how we use these external goods (whether wisely or unwisely)

- Happiness depends on the “education of desire” whereby the soul learns how to harmonize its desires, redirecting its gaze away from physical pleasures to the love of knowledge and virtue

- Virtue and Happiness are inextricably linked, such that it would be impossible to have one without the other.

- The pleasures that result from pursuing virtue and knowledge are of a higher quality than the pleasures resulting from satisfying mere animal desires. Pleasure is not the goal of existence, however, but rather an integral aspect of the exercise of virtue in a fully human life.

The Pursuit of Happiness is an essential human right