To die for one’s country is not only an act of bravery, it is THE act of bravery. For soldiers, it is just an extension of their military career, a part of their duty. As leaders have asked their soldiers to sacrifice themselves for the good of the society, it is only right for leaders to go through the same motion. They should practice what they have preached.

As war is seen as a noble act, tu sat serves as redemption in case of defeat. It is also a way to tell the enemy: “You might have won the battle/war but you don’t deserve to win because you don’t have the chinh nghia (just cause).” And t is not only just cause: it is the moral belief that the cause they are fighting for deserves their total sacrifice.

Although tu sat or tuan tiet means war suicide, there is no good corresponding word in English because the act itself is not practiced in the Christian West. Secondly, the word suicide does not convey the moral and courageous implication of the act. It is a closer equivalent of hara kiri or seppuku (1). Although hara kiri is practically a disembowelment, its practice varies from person to person. If the blade is thrust deeply enough, it could cause an immediate death through arterial bleeding. If inserted superficially, the still-alive victim would be beheaded by the assistant. While tu sat and hara kiri are technically different, the end-result is the same: the death of the person through his own hand or the hands of an assistant.

Vietnam is one of the rare few countries in the world where leaders killed themselves when they lost a war. We will review these cases of tu sat during the pre- and anti-colonial wars and the anti-communist war.

I. PAST TU SAT

At least seven leaders are known to have killed themselves for their country during the anti-colonial war: Vo Tanh, Ngo Tung Chau, Vo Duy Ninh, Truong Cong Dinh, Phan Thanh Gian, Nguyen Huu Huan, and Hoang Dieu. Many more officials could have committed suicide throughout history although their deeds have not been recorded.

1. Vo Tanh and Ngo Tung Chau

1. Vo Tanh and Ngo Tung Chau

Vo Tanh was one of the military warlords from Go Cong in the Mekong delta who had defeated the Tay Son around Gia Dinh Thanh (Saigon) in 1783 (2). Nguyen Anh—the scion of the Nguyen dynasty—realized he needed this valiant free spirit’s assistance if he wanted to succeed in his fight against the Tay Son. He recruited him in 1787 and gave him his sister as concubine. From then onward, Vo Tanh participated in most of Nguyen Anh’s battles against the Tay Son and proved to be one of his best generals. In March 1799, Vo Tanh’s troops besieged Qui Nhon—a port city in central Vietnam—which after four months of resistance surrendered. Nguyen Anh changed the city’s name to Binh Dinh (Pacified). He left Vo Tanh and Ngo Tung Chau in charge of the city and returned to his base in Saigon.

Nguyen Anh at that time was battling a seasonal or “monsoon” war. In the spring, when the winds blew away from the Indochinese peninsula, he loaded his crack troops onto his sailboats in Saigon and headed toward a military target in the Vietnamese central coastal region. He dropped them off close to the target area where he met the rest of his troops that arrived by land. The whole army then attacked the target, which was decisively taken. He left some of his troops to guard the newly conquered area and headed home with the monsoon winds, which in November blew back toward the peninsula. Each year, he thus had a six-to-eight month-window to wage war as the winds shifted bi-annually (3).

Realizing the strategic loss of Binh Dinh, which controlled access to Phu Xuan (Hue)—the Tay Son headquarters—Tay Son General Tran Quang Dieu decided to retake the city and its surroundings. In early 1800, he had his troops guard the land exits of Binh Dinh while a Tay Son naval fleet blocked the sea approach. Nguyen Anh in early April came to the rescue of Vo Tanh who was stuck inside the besieged Binh Dinh. It was a tough battle, which lasted until February 1801 (ten months) before the Tay Son fleet was destroyed after a bloody final 28 hour-sea battle. With the sea approach cleared, Nguyen Anh ordered Vo Tanh to get out of town: the latter refused to leave without his soldiers.

Nguyen Anh realizing that the bulk of the Tay Son troops were encamped in front of Binh Dinh, concluded that Phu Xuan was defenseless and would be an easy target to take. Leaving Vo Tanh to hold the Tay Son army in place, he moved his fleet toward Phu Xuan and then up the Huong River where as expected he encountered minimal resistance. His troops took over the city on June 15, 1801—twenty-six years after he was forced to abandon it.

Binh Dinh was still besieged by the Tay Son. For the last 17 months, the defenders had put up a valiant resistance. Running out of food supplies, they finally decided to kill their animals (horses and elephants) for their meat. Vo Tanh knowing the end had arrived discussed the surrender with General Dieu: he only asked the latter to spare his army. He then had a scaffolding built on which he stacked the remaining gunpowder. Dressed in full military regalia, he got up on the scaffolding and lit up the powder, which blew him up into pieces. That was the signal for his men to open the gates for the Tay Son to take over. Ngo Tung Chau had preceded him in death by taking poison. When General Dieu entered the citadel, he realized how brave his adversaries had been and had their remains buried with honor (4).

2. Vo Duy Ninh

A combined Franco-Spanish force (2,500 French troops aboard 13 warships and 450 Spanish troops on a warship) attacked Danang on September 1, 1858. It met severe resistance from the Hue imperial troops, which were led by General Nguyen Tri Phuong. After five months of fierce combat, the invaders could only control an uninhabited stretch of shore. Frustrated, the French commander Rigault de Genouilly took two thirds of his troops and ships and sailed on February 10, 1859 toward Vung Tau where he thought he would face lesser resistance. He blasted his way along the Saigon River before taking the citadel of Gia Dinh on February 17, 1859 (5).

Aware of the Danang attack by the French, General Vo Duy Ninh, the commander of Saigon-Gia Dinh citadel, thought that his troops needed some re-training to keep them abreast of new tactical maneuvers. The Vietnamese troops used breech-loading muskets and each soldier was able to practice shooting one single round each year. He unfortunately chose the wrong time for the exercise: he did it as the French came to town. The remaining troops that guarded the citadel were unable to hold against the French. Frightened by the massive shelling, they ran away. General Ninh aware of the defeat committed suicide instead of surrendering the Gia Dinh citadel to the invaders (6).

3. Truong Cong Dinh (1820-1863)

3. Truong Cong Dinh (1820-1863)

Dinh, born in 1820 in central Vietnam moved with his father—a colonel—to Saigon. He later married a Dinh Tuong wealthy landowner’s daughter and used his wife’s financial resources to build a don dien (plantation). He enrolled impoverished workers and soldiers to assist him in his agricultural business. After Vo Duy Ninh committed suicide in February 1859, Dinh rallied around him imperial troops that had fled in disarray. With an army of about 1,000 troops, he began a guerilla warfare against the French. His initial military successes led the king to grant him the title of deputy commander of the southern forces.

By 1861, his army grew to 6,000 men to back his military successes. The following year, he was promoted to commander of all the southern nghia quan (volunteer soldiers for a cause). The French were frustrated at not being able to crush the rebels as they were “everywhere and nowhere.” He then moved his troops to Go Cong where he continued his guerilla movement.

When the 1862 Saigon treaty was signed (7), the Hue court cut off its support to Dinh and his nghia quan fearful that the French would use the insurrection as an excuse to expand their southern conquest. The court even ordered Phan Thanh Gian to pressure Dinh to lay down his arms. Dinh not only lost the logistical support of the imperial troops, the French were also free to focus their efforts solely on fighting the rebels. Local people who collaborated with the French gave the rebels new problems. Dinh, however, refused to comply with the court’s pressure arguing that his mandate came not from Hue but from the will of the people in the occupied territories. He gave himself the title of Great General for the Pacification of the Westerners and asked for the financial and moral support of the local people now that he had lost the court’s support.

In February 1863, admiral Bonard encircled Dinh in his stronghold in Go Cong, from which he escaped after sustaining heavy casualties. On August 19, 1863 betrayed by a former rebel, he was ambushed and wounded. Facing imminent capture, he took his own life (8).

Years later, Dinh’s wife returned to her hometown much impoverished. King Tu Duc felt that Dinh was a righteous man who deserved praise. He felt that he needed to support his widow who was alone, poor, sick, and miserable. He granted her a monthly allowance of twenty quan of cash and two phuong of rice. This was more than a mandarin could expect for his pay (9).

4. Phan Thanh Gian (1796-1867)

4. Phan Thanh Gian (1796-1867)

Gian was the first southerner to pass the mandarinate exam—which would qualify him for an administrative or military position in the king’s government—with honors at the very young age of thirty. Many qualified candidates would not pass the exam until their mid forties. In 1831, he was appointed province chief of Quang Nam. The troops he sent to quell a Cham rebellion were defeated and caused him to be removed from his post. Although he was given another position, he learned to accept successes and failures in a dignified, stoic and almost fatalistic manner.

The Hue court at the time of the French invasion was divided between the chu chien (hawks led by Nguyen Tri Phuong, Hoang Dieu, Ton That Thuyet, and Hoang Ta Viem) and the chu hoa (doves led by Phan Thanh Gian, Lam Duy Hiep, Nguyen Ba Nghi, and Truong Dang Que). Despite being hawkish, the chu chien were unable to think of any strategy to oppose the French. They did not contemplate mass resistance probably because the court had in the past so much antagonized the South that any thought in that direction might prove futile. They had taken down the Le Van Khoi rebellion, sentenced the leaders to death and massacred about 2,000 people. They had desecrated Le Van Duyet’s tomb and put three generations of his family to death. They had placed the South under the court’s control and sent all southern generals or lettered men away from the South, the upper leadership of which was no longer native. Southerners no longer felt like trusting the Hue government. The chu hoa felt that they could not resist the overwhelming fire power and military force of the foreigners.

The court sent Phan Thanh Gian and Lam Duy Hiep to negotiate the Saigon treaty, which was signed on June 5, 1862. Besides the loss of three eastern provinces, freedom for Catholic priests to proselyte was granted throughout Vietnam. Tu Duc flew in a rage when he heard the news. By performing a necessary but unpleasant duty, Gian and his colleagues were not only vilified by the common people, they were also rebuked by King Tu Duc who called them criminals (10).

Tu Duc, however, did not take any sanctions against them; on the contrary, he elevated Gian to Viceroy of the Southern Region and Resident Grand Dignitary and Plenipotentiary (Chanh Su Toan Quyen Dai Than). Gian being sixty-seven at that time requested permission to retire, but his request was denied. He was sent to France to negotiate the return of the three eastern provinces although he was not successful. He became aware of France’s technical and military advances. He saw trains running faster and farther than horses, ports crowded with ships armed with powerful guns, and gas lamps burning brighter than oil lamps.

When he told Tu Duc about his assessments, the latter brushed away Gian’s apprehensions by saying:

If faithfulness and sincerity are expressed

Fierce tigers pass by,

Terrifying crocodiles swim away

Everyone listens to righteousness (11).

Tu Duc—as the top Confucian man—implied that the French would respect a man of high rectitude like Phan Thanh Gian. Having seen his powers slipping away from him—loss of three provinces to France, unrest in North and central Vietnam, internal division between the chu chien and chu hoa—he could not help but ask himself why everything was falling apart under him. He probably wanted to reassure himself first. Akin to Montezuma who tried to stop the advance of the Spanish conquistadors with arrows and human sacrifices, akin to Nguyen Van Thieu who in 1975 tried to stop the advancing communists with the magic words of the Paris Agreements, Tu Duc attempted to repel the French with sharpened staves, swords, and righteousness. He would like to change, but the powerful chu hoa were hard to convince.

There was heroism and self-righteousness in abundance in the Mekong delta. Nguyen Dinh Chieu (1822-1888) who was legally blind at that time heaped scorn on those who collaborated with the French. He would not touch anything that was western in origin like soap powder and forbid his children to learn the Romanized alphabet.

How can a man of nghia betray his country?

How can a man of nghia reject his family feelings?

The Vietnamese, however, did not have the economic and technological means to build up a military response. The Hue government, as a Confucian state, did not have a foreign ministry and was not able to keep up with news and advances of the western world. The ministers at the Court locked in their gilded ivory tower and their thousand year-old Confucian learning did not care about what was happening in the modern world. The few who had traveled abroad like Nguyen Truong To and Phan Thanh Gian and talked about western technological advances were simply laughed at.

The French using another pretext conquered three other provinces. Gian was forced to sign the 1867 treaty granting France the whole South—Cochinchina. He returned home dejected and declared:

“But their (French) flag may not be allowed to fly above the fortress while Phan Thanh Gian is still alive.”

He returned to the king all badges of office and the twenty-three royal awards he had acquired during a lifetime of distinguished service and intended to fast until he died. In contrast to other officials, he did not have a big estate or retinue to serve him. He was still alive two weeks later and finally died after taking additional poison (12).

The chu chien sprang into action. They declared him guilty of the loss of the six provinces. Having killed himself, they thought he should be spared of posthumous decapitation. Tu Duc, however, revoked all his titles, positions and grades, had his name removed from the stele of the tien si degree-holders, and ordered his body exhumed and decapitated (tram hau) (13).

“We leave for a thousand generations the sentence of tram hau. Thus we execute those who are already dead in order to warn those who are still living (14).”

Thus died in infamy one of Vietnam’s greatest civil servants. As an abiding Confucian and a victim of the Nguyen’s failed policies of neo-Confucianism and self-isolation (15), he took the blame for the loss of the six provinces with equanimity.

The thousand-generation sentence did not even last one generation. King Dong Khanh rehabilitated him 19 years later in 1886 and returned to his family his titles and medals.

5. Nguyen Huu Huan (?-1875) also known as Thu Khoa Huan (16) was one of the leaders of the resistance movement in the South. He was caught and forced to wear a cangue—a wooden framework around the neck as a portable pillory. It was a sign of infamy. He bit his tongue and died before being executed by the French. He left a few verses, which forever immortalized him.

Folks on both sides, see what I’m bearing here?

A moral burden, yes, and not a cangue!

Beneath its weight, the scholar’s shoulders stoop;

Around its neck, the hero flaunts his pride (17)

6. Hoang Dieu (1829-1882)

6. Hoang Dieu (1829-1882)

Peasant unrest, tribal rebellions, Catholics, pirates, and the Le restoration movements contributed to the chaos in the North, which remained an unsettled region under the Nguyen regime. A French merchant trying to find a way to get to China through the Red river fought verbally with officials in Hanoi. In 1873, French officials in Saigon dispatched Captain Francis Garnier to solve the problem. The French overran the citadel, which was defended by 7,000 men. The 200-men-French force suffered only one casualty and two wounded. They went on and controlled four more provinces in the Red River Delta. Garnier was ambushed by the Black Flag river bandits and killed. A treaty was signed the following year with the Hue Court allowing the French to trade and to proselyte Catholicism all over Vietnam (18).

Chaos resulted as the nghia quan joined the battle against the French. Tu Duc had to call on China for help. In 1882, French troops led by Captain Henri Riviere attacked the Hanoi citadel for the second time. The defense was better this time but the Vietnamese soldiers could not withstand the shelling of the naval artillery. The ammunition depot was hit and blew up. Soldiers scrambled for their lives. The commanding officer, General Hoang Dieu, calmly wrote the report and hung himself from a tree amidst the burning city. His body was brought back to his hometown Quang Nam for burial. Riviere went further but again was ambushed and killed by the Black Flags. It is interesting to note that while Tu Duc could not do anything against the French, the river brigands were able to kill two French officers and hold off their advance.

II. MODERN TU SAT

In 1975, as the fall of Saigon was taking place, many high-level officers and Saigon officials who refused to surrender took their own lives.

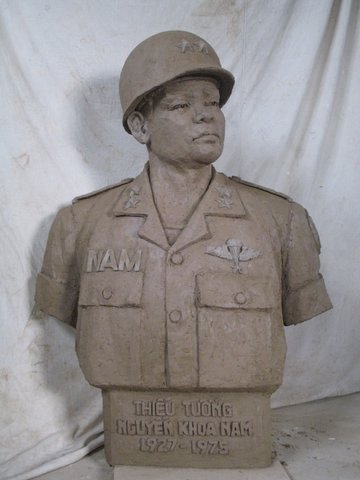

1. General Nguyen Khoa Nam (1927-1975), graduated from the Thu Duc Military Academy in 1953 as an Airborne officer. He fought against the Binh Xuyen in Saigon in 1955, and the Viet Cong around Saigon during the 1968 Tet offensive. He molded the 7th Division into one of the most efficient in the ARVN. As a three-star general and commander of the IV military region (IVMR), he used to drop by to support his soldiers during their military operations. A vegetarian, he led a simple life and followed Buddhist rules closely.

1. General Nguyen Khoa Nam (1927-1975), graduated from the Thu Duc Military Academy in 1953 as an Airborne officer. He fought against the Binh Xuyen in Saigon in 1955, and the Viet Cong around Saigon during the 1968 Tet offensive. He molded the 7th Division into one of the most efficient in the ARVN. As a three-star general and commander of the IV military region (IVMR), he used to drop by to support his soldiers during their military operations. A vegetarian, he led a simple life and followed Buddhist rules closely.

Until the end, he requested every officer and soldier to remain at their post. When designated-President Minh announced his surrender to the communists, he reluctantly went along with the decision. He and General Hung gathered their staff and saluted the South Vietnamese flag one last time at the headquarters court. They then bid farewell to the staff and to each other. He went to the Phan Thanh Gian Military hospital in downtown Can Tho, to comfort and bid farewell to the hospitalized soldiers.

When he returned to the headquarters, he was told that General Hung had taken his life. At 11 p.m., he called Mrs. Hung to offer his condolences. As a man of war, he did not believe in surrendering to people he thought he could defeat. Alone in his office, he put on his official white uniform along with his medals, sat on his desk and shot himself in the head in the early hours of May 1, 1975. His body was taken to the morgue and later he was buried at the Can Tho Military cemetery among his peers. In 1994, his remains were exhumed and cremated. His ashes are stored at the Gia Lam Pagoda in Gia Dinh.

2. Two-star General Le Van Hung (1933-1975) graduated from the Thu Duc Reserve Officers School class 5 in 1954 and was known as one of the five “Tiger officers” of the army. He was made general commander of the 5th ARVN division in 1972 when North Vietnamese General Giap unleashed a three-pronged attack on Quang Tri (I Corps), Kontum (II Corps) and An Loc (III Corps). General Hung and his 5th division defended An Loc for 95 days and defeated an overwhelming enemy force. General Hung was promoted to the post of deputy to General Nam. In late April 1975, these two generals had been offered evacuation thrice, but they flatly declined.

2. Two-star General Le Van Hung (1933-1975) graduated from the Thu Duc Reserve Officers School class 5 in 1954 and was known as one of the five “Tiger officers” of the army. He was made general commander of the 5th ARVN division in 1972 when North Vietnamese General Giap unleashed a three-pronged attack on Quang Tri (I Corps), Kontum (II Corps) and An Loc (III Corps). General Hung and his 5th division defended An Loc for 95 days and defeated an overwhelming enemy force. General Hung was promoted to the post of deputy to General Nam. In late April 1975, these two generals had been offered evacuation thrice, but they flatly declined.

By 4 p.m. on April 30, General Hung was still proclaiming he would not surrender to the Viet Cong. He later met his wife and son and told her to be brave and to raise his son as a man. He gathered his soldiers and told them:

“I will not abandon you in order to evacuate my family. I cannot surrender in this shameful situation. If I have yelled at you on occasions, when mistakes are made, please forgive me.”

He shook their hands and drove them out of his office, after which he locked himself in. A gunshot was later heard. His family and staff broke into the office and found the general, his arms outstretched, still convulsing with blood all over his uniform. He had shot himself into his heart at 8.45 p.m. on April 30, 1975 (19).

3. General Le Nguyen Vy (1933-1975), graduated from the Officers Candidate Course at the Regional Military School, MRII, at Phu Bai near Hue, class of 1951. He was a colonel at the battle of An Loc in 1972. As the attack raged on and as the enemy got closer, he single handedly took an M72 antitank gun to blast away a communist T54 tank. He became deputy commander of the 21st ARVN division and in 1974 went to the U.S. for military training. On his return, he became commander of the 5th ARVN division. When Saigon surrendered, he gathered his staff and bid them farewell. He locked himself in his office and shot himself with a Beretta 6.35. When the Viet Cong officer came to take over the military office, he calmly saluted the general and said:

3. General Le Nguyen Vy (1933-1975), graduated from the Officers Candidate Course at the Regional Military School, MRII, at Phu Bai near Hue, class of 1951. He was a colonel at the battle of An Loc in 1972. As the attack raged on and as the enemy got closer, he single handedly took an M72 antitank gun to blast away a communist T54 tank. He became deputy commander of the 21st ARVN division and in 1974 went to the U.S. for military training. On his return, he became commander of the 5th ARVN division. When Saigon surrendered, he gathered his staff and bid them farewell. He locked himself in his office and shot himself with a Beretta 6.35. When the Viet Cong officer came to take over the military office, he calmly saluted the general and said:

“This is how a general should behave (20).”

4. General Tran Van Hai (1925-1975), then a colonel, had parachuted himself at the famous battle of Khe Sanh in 1968. He became commander of the 7thARVN division in 1974 and was known as a brave and clean officer who also cared for his soldiers. In April 1975, President Thieu offered to take him out of the country, but he refused. He remained at his post and was notified of a heavy concentration of enemy troops across the border in Cambodia. He called the CIA representative to request air support, “We have them in the open. Now is the time to get them…I need help. Help me, CIA man.” But the agent could not do anything and the general later watched hopelessly as the enemy crossed the border and overran his troops. General Hai committed suicide instead of surrendering to the enemy.

4. General Tran Van Hai (1925-1975), then a colonel, had parachuted himself at the famous battle of Khe Sanh in 1968. He became commander of the 7thARVN division in 1974 and was known as a brave and clean officer who also cared for his soldiers. In April 1975, President Thieu offered to take him out of the country, but he refused. He remained at his post and was notified of a heavy concentration of enemy troops across the border in Cambodia. He called the CIA representative to request air support, “We have them in the open. Now is the time to get them…I need help. Help me, CIA man.” But the agent could not do anything and the general later watched hopelessly as the enemy crossed the border and overran his troops. General Hai committed suicide instead of surrendering to the enemy.

5. General Pham Van Phu graduated from the Dalat Military Academy, class 8. He ordered the withdrawal from the II Corps under President Thieu’s insistence. The Viet Minh held him prisoner after the fall of Dien Bien Phu although they later released him. He vowed never to become prisoner of the communists again. He committed suicide on April 30, 1975.

5. General Pham Van Phu graduated from the Dalat Military Academy, class 8. He ordered the withdrawal from the II Corps under President Thieu’s insistence. The Viet Minh held him prisoner after the fall of Dien Bien Phu although they later released him. He vowed never to become prisoner of the communists again. He committed suicide on April 30, 1975.

6. Many more officers had committed suicide during the last days of the war. Colonel Le Cau, commander of the 47th Regiment and Colonel Nguyen Huu Thong, commander of the 42nd Regiment, both from the 22nd Division took their own lives instead of surrendering. Colonel Ho Ngoc Can, commander of the 15th Regiment 9th Infantry Division refused to surrender to the enemy. He and his men fought until the end and he was captured before he could kill himself. He asked to salute his flag the last time before being executed by a communist firing squad. Lieutenant Colonel Nguyen Van Thong saluted the Soldier statue in central downtown Saigon before pulling the trigger on himself. Around 2 p.m. on April 30, after a decent meal Major Dang Si Vinh had his wife and seven children drink some medicine before killing them and himself. His last note: “Forgive us. We do not want to live under a communist regime…” Former Prime Minister Tran Chanh Thanh fearing a fall into the hands of the communists he had deserted before 1954 ended his life by taking poison.

This was a mass tu sat where at least five generals, four colonels, one major and a politician took their own lives in various places throughout South Vietnam.

7. Tran Van Ba belongs to an illustrious pedigree of southern Vietnamese nationalists. His great uncle Bui Quang Chieu—the founder of the Saigon Constitutionalist Party—was assassinated along with his four sons and a daughter in 1945 by the communists. His father Tran Van Van, a member of the South Vietnamese National Assembly, was also assassinated in 1966. Smuggled to France one month after his father’s death, Ba became President of the Vietnamese Students Association from 1972 to 1980 and denounced Hanoi’s “summary executions, military expansionism to Cambodia and Laos, and inducing the exodus of the boat people.” He returned to Vietnam in 1980 to continue the fight for freedom and democracy in his own homeland. He was jailed in 1984 and executed on false charges of treason in January 1985 despite international protests—including those of France President Valery Giscard d’ Estaign, Simone Veil and Laurent Fabius (21).

7. Tran Van Ba belongs to an illustrious pedigree of southern Vietnamese nationalists. His great uncle Bui Quang Chieu—the founder of the Saigon Constitutionalist Party—was assassinated along with his four sons and a daughter in 1945 by the communists. His father Tran Van Van, a member of the South Vietnamese National Assembly, was also assassinated in 1966. Smuggled to France one month after his father’s death, Ba became President of the Vietnamese Students Association from 1972 to 1980 and denounced Hanoi’s “summary executions, military expansionism to Cambodia and Laos, and inducing the exodus of the boat people.” He returned to Vietnam in 1980 to continue the fight for freedom and democracy in his own homeland. He was jailed in 1984 and executed on false charges of treason in January 1985 despite international protests—including those of France President Valery Giscard d’ Estaign, Simone Veil and Laurent Fabius (21).

The 2007 Truman-Reagan Medal of Freedom was posthumously awarded to Mr. Ba at the embassy of Hungary in D.C. on November 15, 2007. A memorial has been erected to Mr. Ba in Liege, Belgium and a street dedicated to him in Falls Church, VA by the Vietnamese community (22).

By returning to Vietnam to fight communism, Ba knew he could be taken prisoner, jailed and possibly executed. He went ahead anyway.

III. DISCUSSION

Southerners have put up resistance against the French first then the communists. This may reflect the fact that in the 19th century the French landed first in the South forcing them to bear arms against the invaders. In the 20th century, southerners fought against the communists who had taken the power in North Vietnam in 1945.

Vo Tanh and Ngo Tung Chau fought for the South. They sacrificed themselves to preserve their honor and not to fall in the hands of their enemies, the Tay Son. They at the same time tried to preserve their moral purity

All these heroes lived for their nghia (righteousness): duty to their king and country. As Phan Thanh Gian was sixty-seven—this could be equivalent to today’s 80 or 85—he no longer wanted to work and had asked to retire but at the king’s insistence, he took on the position of Viceroy of the South. This was also a losing proposition because there was no way anyone could defend the South against the French who were mighty militarily as well as eager to conquer Vietnam. He had asked Tu Duc to reorganize the army, buy new guns and artillery pieces, but to no avail. The end-result was foreordained. Despite all these facts, he tried to deflect the blame away from the king by assuming himself all the blame.

Truong Dinh wanted to fight on but the king told him to lay down his arms. He decided to carry on the insurgency anyway making sure to deflect the blame away from the king.

During the anti-communist war, 300,000 South Vietnamese soldiers had lost their lives to defend South Vietnam against the Hanoi government. They were great, courageous men who had dedicated their lives to their country. When the latter sank, some killed themselves rather than surrendering. Instead of flying out, they preferred to die in their old Vietnam. The U.S. offered to fly Generals Nam and Hung out of the country, but they refused, accepting to die instead among their soldiers. General Le Minh Dao, the commander of the Xuan Loc region—the last bastion of resistance against the North Vietnamese during the Vietnam War—also declined to be air lifted by the U.S. in April 1975: he ended up being confined in a concentration camp for the next 18 years during which he almost lost his life. There was no greater dedication and self-sacrifice than this.

These people had a very high sense of responsibility and morality. They were ashamed of handing over the troops under their command to the enemy or to turn themselves in. They felt they were betraying “not their emperor, but a sovereign state that had ceased to exist long before, whose ideals they, as military officers, still respected (23).” Although South Vietnam had lost the war, the fact that five generals and scores of colonels and other officers and civilians took their own lives at the end of the war showed that there was something bigger and larger than defeat or victory. There was pride and belief that what they were fighting for—freedom and dignity of human life—was worth more than life itself. By sacrificing themselves, they implied that life without freedom was not worth living. By dying, they made a mockery of communism, a theory they fought against and died to resist it.

Westerners do not believe in taking their own lives when they lost the ultimate battle, although it is a known fact that ship captains would go down with their sinking ships. South Vietnamese Captain Nguyen Van Tha indeed went down with his destroyer HQ10 during the Spratly Islands (Truong Sa) battle against the Chinese in 1974. Easterners, on the other hand, were willing to die following crucial battle losses in order to preserve their honor. They did not want to surrender, to be caught and have to go through the shame of being held prisoner. By taking their own life, they still felt they had the control of their lives or had redeemed their honor.

One soldier preferred to die with his glory intact. The other was willing to suffer from the humiliation of defeat. There is no intention to belittle those who had surrendered. They did it for various reasons: to save their troops or the civilian population; or because the commander-in-chief, President Duong Van Minh ordered them to surrender.

Each man chose his version of glory, each man his pain and suffering. There is no right or wrong solution to the problem. Each person was the master of his own life. What is unique about the Vietnamese (at least the South Vietnamese) culture is that over many centuries, tu sat has been a part of their tradition. The Japanese share a similar tradition. Great numbers of officers, soldiers, and even civilians killed themselves when faced with defeat and the prospect of capture. They felt a man with honor would not allow himself to be captured by his enemy. Only hara kiri could erase shame, express ultimate devotion, or register protest (24)

It should be noted that South Vietnam has been in existence since 1600 (25) while communism has been present only during the last seven decades. While southern nationalists believed in tu sat, northern leaders who demanded that soldiers sacrificed themselves for the Party, did not. Although General Vo Nguyen Giap who had sacrificed—in Vietnam we use the word nuong or roast—tens of thousands of North Vietnamese soldiers during the Tet attack and lost many more during the 1972 Eastern Tide attack had been demoted from his position of Commander of the People’s Army, he still held on to power and did not believe in killing himself.

IV. CONCLUSION

This study reveals a fairly high number of cases of tu sat throughout the centuries in Vietnam. Tu sat seems to be a unique southern nationalistic Vietnamese tradition akin to the Japanese hara-kiri or seppuku.

NGHIA M. VO

NOTES

1. Seppuku is the correct term while hara kiri is the commonly used word. The person disemboweled himself with his own sword and was beheaded by his assistant who in a sense completed the victim’s work.

2. The South (dang trong) had seceded from the North (dang ngoai) in 1600. During this revolutionary period (1771-1802), there was no central government in the South because the southern Nguyen had been toppled by the rebels Tay Son. The latter had expanded their control over the present-day central Vietnam while the Nguyen scion—Nguyen Anh—barely had control of the Mekong delta. In the North, the Chua Trinh controlled the house of Le. The warlords therefore roamed freely. They raised their own armies and fought for whomever they liked.

3. Nguyen Anh took 26 years to recover his ancestors’ throne. He was a methodical, conscientious, and careful person. Part of this had to do with the fact he had to rebuild his governmental infrastructure to raise funds to continue the war. Second, he wanted his army to have sufficient supplies and food they could use without having recourse to stealing from people. Everywhere his army went, he had new granaries built for their needs. Third, having lost many battles in the beginning of the war, he knew that help could come only with strings attached to them.

4. Le Thanh Khoi. Le Vietnam. Paris: Les Editions de Minuit, 1955: 318-21

5. McLeod MW. The Vietnamese Response to French Intervention 1862-1874. New York, NY: Praeger 1991: pp 43-44.

6. Ibid pp 52.

7. The three provinces of Bien Hoa, Gia Dinh Dinh Tuong were ceded to France along with a few commercial ports. The Catholic religion could be practiced freely throughout Vietnam.

8. McLeod pp 63-65.

9. Ibid 74.

10. Ibid 50-54.

11. Tran My Van. A Vietnamese Royal Exile in Japan.

12. Vo NM. Roots of Southern Nationalism in Vo NM, Dang CV, Ho HV. The Sorrows of War and Peace. Denver, CO Outskirts 2008 p 49.

13. The names and birthplaces of the graduates of the triennial examination are chiseled in stone steles that sat on stone tortoises housed at the Van Mieu (Temple of Literature). How could anyone decapitate a skeleton is anyone’s guess? But the king’s ruling had to be carried out and the decapitation had to be done.

14. McLeod pp 55-56

15. When Gia Long recovered his throne in 1802, his biggest mistake was to return to the old Confucian system to prop up his regime. Locked in this mentality, he and his descendants completely sealed their country (be quan toa can) to modernization and trade. This procedure in the end weakened their regime so much that it could not put up any resistance against the westerners. A few thousands of soldiers armed with guns and artillery were able to take over the whole country in a few years.

16. A cu nhan graduate of the regional examinations of 1852.

17. Translated by Huynh Sanh Thong. An Anthology of Vietnamese poems. New Haven, Yale. 1996: 84.

18. Jamieson NL. Understanding Vietnam. Berkeley, California 1995: 47-48

19. Dommen AJ. The Indochinese Experience of the French and the Americans. Bloomington, IN; 2001: 921-924

20. Vo NM. The Bamboo Gulag. Jefferson, NC: McFarland 2004 18-21

21. Follorou J. Quand la France cede aux pressions du Vietnam a propos d’une stele d’un square parisien. Le Monde 9/23/2008: http://www.lemonde.fr/asie-pacifique/article/2008/09/23/quand-la-france-cede-aux-pressions-du-vietnam-a-propos-d-une-stele-d-un-square-parisien_1098526_3216.html

22. www.victimsofcommunism.org

23. Dommen p 923.

24. French, SE. Code of the Warrior. Lantham, MD, Rowman & Littlefield 2003: 220-223.

25. Vo NM. Roots of South Vietnamese Nationalism in Vo NM, Dang CV, Ho HV. The Sorrows of War and Peace. 2008: 37-38.

3 Comments

ultrasound technician

Great information! I’ve been looking for something like this for a while now. Thanks!

wiosenne buty damskie

Your method of explaining the whole thing in

this piece of writing is really fastidious, all be able to simply know it, Thanks a lot.

SEO Marazion

I’m more than happy to discover this page. I need to to

thank you for ones time for this particularly wonderful read!!

I definitely loved every part of it and i aso have you book-marked to see new information in your site.

Feel ree to surf to my webpage; SEO Marazion