Miami (CNN)

A satellite on the verge of falling back to Earth appears to have begun slowing down but will not re-enter the atmosphere until late Friday or early Saturday U.S. time, according to NASA.

The United States is once again an unlikely but potential target for the 26 pieces of the Upper Atmosphere Research Satellite, expected to survive the descent. Those pieces, made of stainless steel, titanium and beryllium that won’t burn, will range from about 10 pounds to hundreds of pounds, according to NASA.

NASA said Friday morning that it would be hours before it would be able to zero in on the time and place of the re-entry.

Mark Matney of NASA’s Orbital Debris team in Houston said there’s no way to know exactly where the pieces will come down.

“Keep in mind, they won’t be traveling at those high orbital velocities. As they hit the air, they tend to slow down. … They’re still traveling fast, a few tens to hundreds of miles per hour, but no longer those tremendous orbital velocities,” he explained.

Because water covers 70% of the Earth’s surface, NASA has said that most if not all of the surviving debris will land in water. Even if pieces strike dry land, there’s very little risk any of it will hit people.

However, in an abundance of caution, the Federal Aviation Administration on Thursday released an advisory warning pilots about the falling satellite, calling it a potential hazard.

“It is critical that all pilots/flight crew members report any observed falling space debris to the appropriate (air traffic control) facility and include position, altitude, time and direction of debris observed,” the FAA statement said.

The FAA said warnings of this sort typically are sent out to pilots concerning specific hazards they may encounter during flights such as air shows, rocket launches, kites and inoperable radio navigational aids.

NASA says space debris the size of the satellite’s components re-enters the atmosphere about once year. Harvard University astrophysicist Jonathan McDowell noted that the satellite is far from being the biggest space junk to come back.

“This is nothing like the old Skylab scare of the ’70s, when you had a 70-ton space station crashing out of the sky. So, I agree with the folks in Houston. It’s nothing to be worried about,” McDowell said.

Pieces of Skylab came down in western Australia in 1979.

The only wild card McDowell sees is if somehow a chunk hits a populated area.

“If the thing happens to come down in a city, that would be bad. The chances of it causing extensive damage or injuring someone are much higher.”

NASA said that once the debris hits the atmosphere 50 miles up, it will take only a matter of minutes before the surviving pieces hit the Earth.

CNN’s Mike Ahlers contributed to this report.

Falling Satellite Debris Might Hit U.S.

NASA on Friday warned there was still a small chance that remnants of a falling research satellite could end up in parts of the U.S., though scientists weren’t able to predict the precise trajectory or exactly when the space junk would reach the ground.

The difficulty of pinpointing where the parts will land highlights broader international concerns about tracking more than 20,000 pieces of orbiting space debris, some no larger than a football. Experts say the debris poses a potential threat to commercial and military satellites, as well as to the international space station.

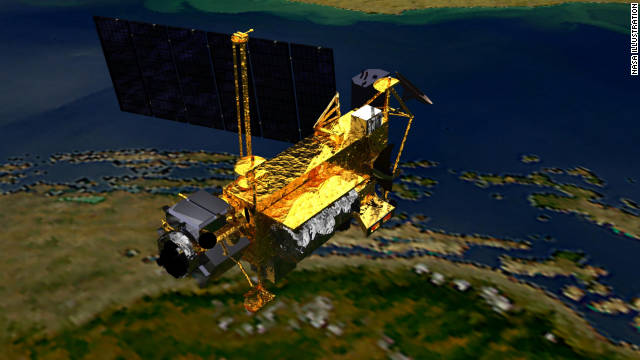

The anticipated breakup of the defunct, 13,000-pound NASA climate satellite, set to tumble uncontrolled through the atmosphere after 20 years of operation, could result in dozens of pieces hitting the Earth by early Saturday. Most pieces are expected to burn up as they streak through the atmosphere, though experts at the National Aeronautics and Space Administration have indicated that some could survive re-entry and possibly weigh hundreds of pounds.

After days of being unable to say precisely where the shower of parts is likely to land, NASA’s website said Friday there was “a low probability” of pieces ending up in North America. The agency said it couldn’t rule out the possibility of parts hitting the U.S., partly because solar flares have caused disruptions in the atmosphere. Such a scenario, according to NASA, “cannot be discounted.”

The risks posed by orbiting debris, a topic that increasingly preoccupies some military and aerospace experts, are significantly greater. The debris is essentially the unavoidable residue of hundreds of rocket launches, exploration missions and other man-made objects left circling the Earth.

With an estimated 750 or more satellites currently in orbit—and many more nations now seeking to launch satellites than ever before—overall collision hazards are expected to increase. Experts worry the threats are particularly significant around some widely used orbital locations. Astronauts aboard the international space station periodically are forced to take emergency steps to deal with threats.

Two years ago, a drifting and powerless Russian satellite smashed into and destroyed a commercial satellite operated by Iridium Communications Inc., a provider of phone and data services based in McLean, Va.

The collision occurred because Pentagon radar sites on the ground and U.S. government assets in space weren’t closely tracking the merging courses of the two satellites. At the time, top Air Force officials said the U.S. had the capability of closely tracking and issuing pre-collision warnings for only a couple of hundred pieces of orbiting debris.

Since then, both military and commercial satellite-operators have put greater emphasis and resources into tracking space debris.

Surveillance efforts have been stepped up; military and corporate experts have shared information about the condition and orbits of satellites; some manufacturers have recommended installing additional sensors on satellites to warn of potential threats; and there has been enhanced international cooperation to try to avoid in-orbit surprises.

Andy Pasztor